You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Social theorist Talcott Parsons once said that tenure in the American university is like marriage. The institution places a high degree of trust in the tenured professor, for better or for worse, in sickness and in health -- forever.

The institution of marriage has been much in the public eye of late, so allow us to carry the metaphor a bit further. Writing in 1973, Parsons had little inkling of the university’s growing commitmentphobia. Today, the American university would really just prefer to be friends -- with benefits, of course. Two out of every three hires today is a contract faculty member: a non-tenure-line, contingent employee. Although we focus on midcareer faculty in our columns, many contract faculty members are also midcareer -- well past the early career stages, but without the benefits of long-term commitment.

Adjuncting was once seen as a passing career stage, particularly for recent Ph.D.s on the market. But most contract faculty members are, in fact, in the middle of their careers and have been working as contractors for well over six years (the time it takes to get tenure). The largest proportion of part-time contract faculty falls between the ages of 56 and 65. At our own university, where we conducted an analysis of the work experiences of contract and tenure-line faculty, the median age of full-time contract faculty was 45 years old, only a few years younger than the median age of our associate and full professors.

Contrary to common belief, only a minority of contract faculty teach as a side job to a primary occupation. And the majority of part-time contract faculty report that they would prefer a tenured, full-time position, given the opportunity. Not long ago, the future looked promising for tenure-aspiring academics, at least demographically. Baby boomers were on the verge of retirement and the “echo boom” millennial generation was just reaching college age.

But instead of expanding the tenure pathway, many of those new positions were simply converted to cheaper, expendable contract labor positions. The increased reliance on contingent faculty has created a trifurcated system, with tenure-line, full-time contingent and part-time contingent faculty experiencing inequalities in the experience and rewards for their positions, as well as a loss of academic community.

Although most of the growth in contract faculty has occurred at community colleges, it is also prevalent in other institutions. Full-time and part-time adjuncts make up between 51 percent (public) to 65 percent (private) of the faculty at doctoral institutions. To justify the lower pay of contingent faculty, it is often assumed that they are “less than,” “different from” and otherwise separate from their tenure-line colleagues.

Yet this is increasingly difficult to argue in today’s highly competitive and overcrowded academic job market. At doctoral universities, most contract faculty members have doctoral degrees, and many have strong research records coming out of graduate school. And the distribution of work they do once hired at research universities actually looks much more similar than different.

Comparable Demands

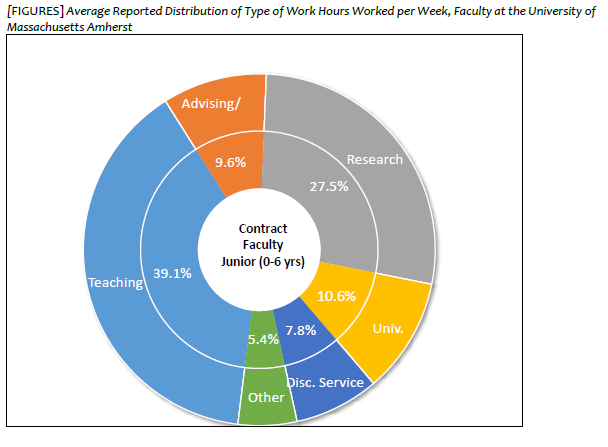

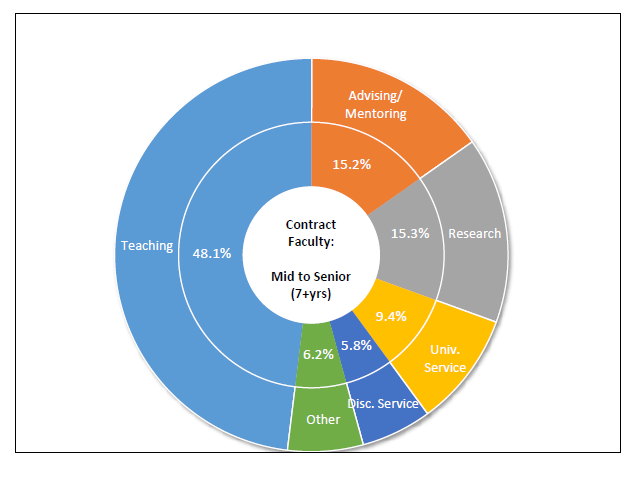

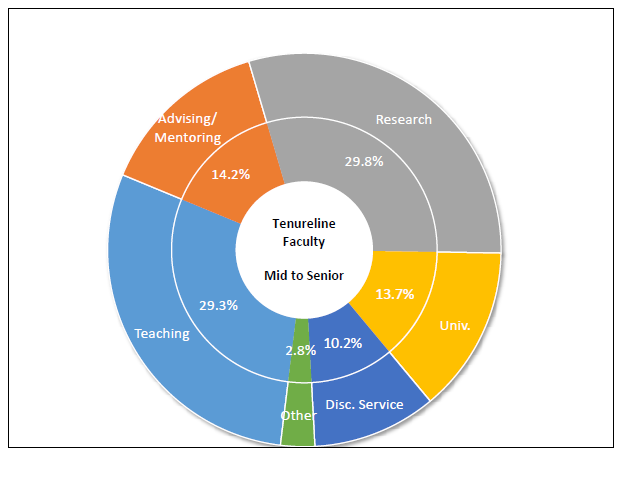

Our study at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst comparing full-time tenure-stream and contract faculty documents remarkable similarities between the types of work they do. Rather than focusing only on teaching or research, contingent faculty appear to be balancing research, teaching, mentoring/advising and service in ways similar to tenure-stream faculty. The charts compare the proportion of reported hours worked per week in various capacities across more junior contract faculty (those working as contracts for six or fewer years), midcareer and senior contract faculty (those working for seven or more years) and tenured professors as a comparison point.

As the data show, early-career, full-time contract faculty members at our university are doing more research, service and mentoring than what might conventionally be expected. Since many are on temporary teaching contracts that may not get renewed, they are under great pressure to remain marketable in case they find themselves without a job. One lecturer said, "When we are on one- to two-year contracts, we have to do the professional development; if you don't, you shoot yourself in the foot."

Without opportunities for research-oriented professional development (conference attendance, research time, lab space, presentations, publications), contingent faculty must work overtime to engage in their scholarship. In our study, almost all contingent faculty members emphasized the need to continue their research so they could remain current in their field.

Midcareer and senior contract faculty report less time researching and more time teaching than their junior colleagues. This may indicate that that they have given up the search for a tenure-track position and are increasingly turning toward instruction. Nevertheless, they still perform a substantial amount of advising and mentoring, as well as service to the college or university and to the discipline. Thus, even as the institution distances itself from its responsibilities to faculty, contract faculty members are behaving in more committed ways to it than ever. The amount of service work that contract faculty members do may also reflect that the institutional service burden has become too large to be shouldered by a proportionately shrinking tenure-line faculty.

One of the concerns that contingent faculty voiced in our focus groups had to do with their increasing role in service and administrative work, which was rarely recognized or even, they argued, compensated. Being involved in administration and governance leads to difficult trade-offs, especially for those with high teaching loads. As one contingent faculty member reported, it feels like “doing two jobs at once. Teaching a 3-4 load, while also performing a huge staff position.”

Contingent faculty also expressed concern about how difficult it can be to turn down service requests. One observed, “We can never turn down a request with the justification that it will hurt the quality of our teaching the way [tenure-line faculty] can do for the sake of research.”

Contingent faculty worried that the institution was placing increasing pressure on them to carry out service work. As one contingent faculty member argued: “As a lecturer, there is a very big push to protect pretenure faculty, not loading them down with administrative work so that they can meet the unrealistic expectations regarding research. Lecturers get dumped on; we don't have a way to protect our jobs because our job is not defined.”

Our unionized campus is not representative of all of higher ed. The fact that we are a public university has made it much easier for our faculty to bargain effectively than at private universities, thanks in no small part to the National Labor Relations Act. Many unionized campuses have fought against the turn to contingent faculty; however, only some include such faculty within their ranks.

At the University of Massachusetts, the faculty union is comprised of all faculty members, whether contract or tenure line, full-time or part-time. Because of our union, our contingent faculty members have more protections than their nonunionized counterparts elsewhere, and they have career ladders in place to senior lecturer and senior lecturer II, which come with pay bumps and greater security.

While that may mean that the variety of work we show in the pie charts is unusual, we believe that contingent faculty at many other institutions also look more like than unlike their tenure-stream colleagues, and perhaps even more so due to more exploitative conditions. Data collected through the National Study of Postsecondary Faculty show that, nationwide, contingent faculty engage in research, service and advising -- in addition to teaching.

The Need for Reform

The exploitation of adjunct faculty, particularly of part-timers, requires reform. To boot, we know that inequality often has pernicious effects on all of society -- even on the elite who benefit from their positions of privilege. In the short term, tenured faculty may feel they are the chosen few, but they lose out in ways they may not recognize from the shift to contingent employment. With proportionally fewer tenure-line faculty, faculty self-governance suffers, and the burden of departmental and university service increasingly falls on associate and full professors.

Students also lose out. Although contract faculty are often gifted teachers (one study shows they earn higher teaching evaluations than tenure-track faculty), their institutional position compromises their full potential. They often have heavy course loads, lack office space and are paid only for their time inside the classroom, not for meeting with and mentoring students outside the classroom. Students are unable to form a lasting mentoring relationship with faculty members whose time at the university is fleeting.

One contingent faculty member told us, “Advising and a letter of recommendation is what you are doing with your students. If the person who made this relationship with the student … is gone after a year it is a disservice to the students … Students are the big loser with the current system.” Just as colleges and universities refuse to commit to the adjunct professor, the often transient nature of their employment makes them unable to commit to their students longer than a semester or two.

But the highest price is to society itself. The decline and eventual disappearance of tenure in higher education means an end to academic freedom. Tenure makes academe one of the few remaining public spaces with strong protections from the market, where tenured employees are able to undertake high-risk research and challenge conventional thinking in the interest of the common good. According to the American Association of University Professors' 1940 statement on tenure, “Freedom in research is fundamental to the advancement of truth. Academic freedom in its teaching aspect is fundamental for the protection of the rights of the teacher in teaching and of the student to freedom in learning.”

To return to our initial marital metaphor, the stance of the modern university may best be captured by the dated adage, “Why buy the cow when you can get the milk for free?” If contingent faculty members are increasingly doing the work of tenure-line faculty at cheaper pay and with no protections of tenure, what financial incentive does the university have to stem the tide of change to contingent labor? On its face, the cost of tenure for universities appears high, but the long-term benefits to academic freedom are invaluable.

At the very least, contract faculty members should be compensated for comparable work, and the departments that employ them should recognize their contributions. But, ultimately, to preserve the survival of academic freedom, colleges and universities must commit to their faculty as a whole and take a stand against the erosion of tenure. It is high time for a renewal of marriage vows.