You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

My position at Greenback University is in the Sustainability Office, which is located on the operations side of the house. Our primary responsibility is to get the campus operating less unsustainably although, to that end, we actively participate in curricular and co-curricular efforts to get students to understand and expect some level of sustainability.

Any time I go into the classroom, of course, I'm there at the invitation of some faculty member. At Greenback, as at probably every other school, there's a wide variety of faculty committed to the principle of sustainability. At the same time, it's safe to say that not all of these professors envision sustainability in consistent ways. And probably none of them envision it in the same way I do.

As far as the suits to whom I report are concerned, sustainability is about reducing Greenback's greenhouse gas emissions (because our President signed a commitment that we would do that), and achieving the reduction by expending as little money as possible. That last bit they think of as "economic sustainability". In that, they're largely wrong.

As far as the faculty with whom I interact are concerned, sustainability is some combination of reduced environmental impact, near-Deweyan democracy, social justice and an adequate standard of living for all. The interplay between considerations of environmental, social and economic sustainability is different for each professor. In truth, some of them treat the environmental aspect almost as if it were moot.

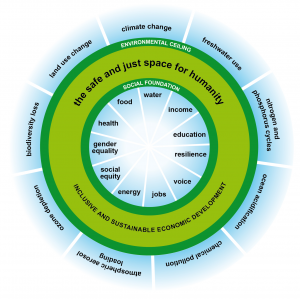

The person who's done the best job I've yet seen of reconciling these various perspectives on sustainability into a single comprehensive picture is Kate Raworth, formerly of Oxfam. Raworth has come up with a concept she calls the "Doughnut economy", consisting of the space that's encircled by a spectrum of biophysical constraints and comprehends the range of psycho-socio-economic requirements. What she's limned out is not any particular form of economic activity, but rather the conceptual space within which truly sustainable economic activity can take place. She gives a reasonable explanation of the concept here, but the gist is evident in the doughnut diagram itself:

\

\

It's hard to disagree with Raworth's logic -- if any society is to conduct economic (or other) activity sustainably,that activity must be conducted within the constraints imposed by biophysical reality, and it must also fulfill society's own basic needs (however defined). In practice, of course, there's no empirical proof that such a conceptual space has any counterpart in the real world. It may -- some definable configuration of activity may meet all the requirements without exceeding any of the constraints. But until such a real-world example can be set forth, the possibility exists that Raworth's diagram corresponds to a set of mathematical equations for which there simply is no solution. Which, if true, would mean that some sub-optimal solution would be required for society to persist ("sustainably" or not). Which would mean that some compromise would be required. Which, in turn, would indicate the need for some set of priorities.

When it comes to prioritizing Raworth's basic set of factors, the ones on the outer ring quickly sort to the top. We, as a society and very possibly as a race, can't survive in an absence of fresh water or arable land. We have very limited ability to survive extreme chemical pollution or ozone depletion. We won't last long if the bio-diverse ecosystem collapses around us. The constraints implied at the outside of the doughnut may not be precisely quantified but, regardless, are absolute.

Some of the requirements which form the inner ring of the doughnut seem similarly non-negotiable. We, and the societies within which we live, are dependent on food, water, health and resilience. The social mechanisms which currently serve us deliver these through a combination of income and education; the economic mechanisms deliver by means of jobs and energy. But while I'm all in favor of voice, social equity and gender equality, I have trouble seeing the lack of any of those in the same existential terms as I do a lack of food or water or a tolerable climate.

We can't allow the ideal to become the enemy of the necessary. Our immediate-term problems lie more in the fact that our political economic practices and norms have taken little account of the finite nature of the world in which we live than they do in the (equally inarguable) reality that those same practices and norms perpetuate racism, elitism, poverty, misery and injustice. It will behoove us little to become more egalitarian if, at the same time, we elevate the growth of GDP above all other goals -- if we continue to focus our collective energies on increasing the rate at which we turn the Earth's natural wealth into poison, pollution and dross. Perhaps all elements of Raworth's diagram need be addressed, but it's certainly true that some need be addressed with more urgency -- at higher priority -- than others.

I worry that we're not teaching that sort of sense of priority to our students at Greenback, with the possible exception of the handful of Philosophy majors who get a course in Utilitarianism, It ought to be one of the key learning outcomes we expect of all our graduates. Right there with an understanding, and appreciation of the value of sustainability.