You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

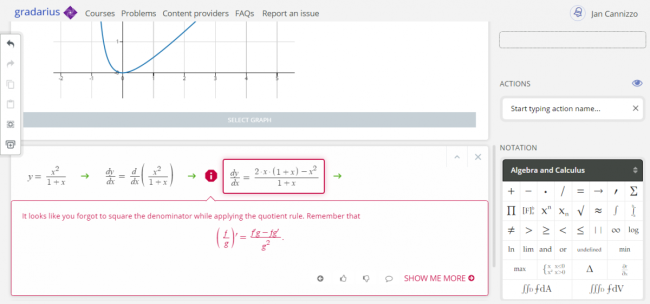

Screenshot of the Gradarius platform

Stevens Institute of Technology

A few years ago, math instructors at Stevens Institute of Technology noticed their calculus students consistently struggling with the basics once they reached upper-level courses -- or, in some cases, they were failing their introductory courses and abandoning math altogether.

The crux of the problem, it seemed, was that students at the New Jersey institution struggled most while doing homework, away from the instructor or anyone else who could help.

“People could do well in calculus but learn nothing,” said Alexei Miasnikov, professor and director of the department of mathematical sciences at Stevens.

After several years of tireless software development, along came Gradarius -- a tool developed at Stevens that has replaced written homework assignments and even textbooks in all of the institution's face-to-face Calculus 1 and 2 courses. Gradarius offers automatic, real-time feedback, guidance and encouragement as students show their work.

Other institutions -- Pennsylvania State University, Arizona State University and Hunter College among them -- have started using the tool, and it's drawn positive feedback from students after some initial kinks were worked out. Miasnikov said he’s glad to have created the new tool but now realizes the enormity of the task he gave himself.

“If I had known how difficult this is, I would have never started doing it,” Miasnikov said. “There were a lot of headaches.”

Long Road to Success

Development of Gradarius began in 2010, when Miasnikov and his team determined that software in the area of math homework help was mostly limited to lower-level disciplines like algebra and geometry.

Using investments from family and friends as well as volunteer hours, developers fused computational algebra research and algorithms with adaptive learning techniques. This advanced combination of technology is currently patent pending, and it aims to take the place of a “seasoned tutor,” Miasnikov said. The name comes from Latin for “progressing step by step.”

One of the biggest hurdles to overcome was creating a program that acknowledged the myriad approaches students could take to a single calculus problem. Accounting for those variables took several years and quite a few episodes of trial and error, Miasnikov said.

"We were very experienced in building software systems for various symbolic and algebraic computations, but to make one which can be used in classrooms and at home by thousands of students brings absolutely different requirements," said Miasnikov, who cultivated his skills in software development with substantial National Science Foundation grants earlier in his Stevens career.

The technology also connects students to instructors even when they’re not in the same room. Instructors can view students’ step-by-step processes and the false starts and confusion points that led them to their solution.

The software wasn’t an instant hit with students. When Jan Cannizzo, teaching assistant professor in the department of mathematical sciences, introduced the tool in his class a couple years ago as a replacement for a few homework assignments, students balked at the lack of introductory or training materials to get them acquainted with the software, and they struggled to navigate the clunky user interface.

“We had a lot of criticism from the students. It was really an impetus for us to change the software and keep working on it,” Cannizzo said. “It’s much, much better than it was then.”

Instructors also learned the software through “trial by fire,” Cannizzo said. Once he got comfortable with it, he created a hybrid version of his course that combined traditional writing assignments with Gradarius homework. As students grew more accustomed to Gradarius, Cannizzo phased out written homework altogether, followed by the textbook.

Positive Impact

In addition to difficulties with offering in-depth grades and comments on written calculus homework, Cannizzo often found that students simply skipped assignments or submitted “shoddy work.” Gradarius holds them accountable.

It also helps Cannizzo and fellow instructors focus on substantive material during lectures. Now they’re not as focused on basic problem solving; Gradarius takes care of that for them.

“It was part of our mission to not make calculus just this dry, rote memorization type of subject,” Cannizzo said. “We have found time to focus more on concepts during lectures.”

Miasnikov believes Stevens students' struggles with calculus were rooted in a K-12 emphasis on "cumbersome procedures that allow one to get the answer to some very particular standard questions." He hopes Gradarius will help students overcome that lackluster training.

Future plans for the software include incorporating more instruction via text, images and links, and to bring the tool to online courses that would require “a minimum amount of human instructor supervision.” One idea for that course is a two- to three-week calculus refresher that students who need help with the basics can take right before or during a more advanced calculus course -- particularly useful for transfer students who might have had different material in previous math courses, Cannizzo said.

“I personally am concerned a bit about losing the human element of instruction,” Cannizzo said. “It’s not like we intend these online courses to replace curriculum. They’re really supplementary.”