You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

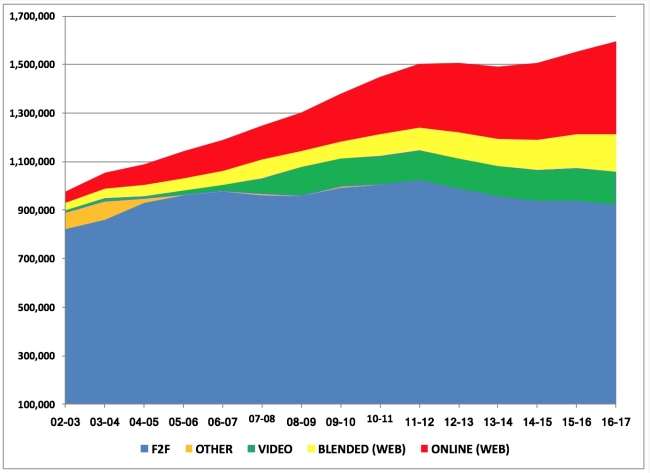

UCF student credit hours

University of Central Florida

The little engine that could has had a terrific run.

After two decades, new federal data show that 6 million U.S. college students now take one or more distance education courses, an increase of more than 250,000 in 2015, or more than a quarter of all U.S. students. Until recently, virtual students racked-up double-digit gains, year after year, far outpacing no-growth, residential numbers. It’s one of the great American higher education success stories.

Perplexingly, the data also show a slackening of the online curve, with digital enrollment recently puffing along modestly at 3 to 4 percent a year, not with its historic hockey-stick muscle. Some observers say that online may be running out of steam, calling digital growth “sluggish,” “flattening,” or “hitting a plateau.”

Others—like me—are less pessimistic, claiming there’s still fire in the belly. The big news from the just-released Digital Learning Compass study tells a strikingly up-beat story. Dramatically from 2012 to 2015, for-profits took a huge hit, while large private nonprofit institutions and big state schools steamed ahead. If we look closely at supply and demand, however, we may be able to make sense of what’s behind the numbers.

Demand

Eager to uncover what’s happening, investigators check-off five common market forces they say account for most fluctuations—declining demographics, showing a shrinking U.S. college-age population; troubling rates of family income inequality, forcing away many from poor and middle income families; an improving job market, attracting greater numbers to a more accommodating workplace; rising numbers of adult learners; and, crucially for digital education, stiff competition, with dozens of new virtual programs chasing after fewer and fewer students.

Plus there is a new competitive intruder—MOOCs. With MOOCs giving away college courses to your potential customers, the result is certain to have a depressing effect on your sales. We’ll never know how many of the 58 million learners who took a free ride on MOOCs would have enrolled in university courses and paid tuition for the privilege. MOOCs have demonstrated that there is a huge reservoir of internet fans out there, taking Coursera and edX digital classes, but not nearly as many are signing up at your local college.

These and other marketplace factors effect both on campus and online enrollments, but they’ve been hammering the residential population brutally, bleeding more than 250,000 on-campus students nationwide by fall 2015. Were it not for online, Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, producer of the widely followed annual survey on virtual education and the Digital Learning Compass report, told me that the total loss of the nation’s university population would have exceeded one million in 2015 over the previously reported year.

Supply

While fluctuations are commonly attributed to demand—increasing or decreasing numbers of customers purchasing your product—surprisingly little attention has been given to supply; that is, the flow of new offerings in university course catalogs. Studying the digital education economy with your finger on the scale of the marketplace tends to unbalance the equation. With a heavy hand on sales and little or no attention paid to production, observers may be lead down a blind alley.

Andy Grove, founder and former CEO of Intel, famously said, “The Internet doesn’t change everything. It doesn’t change supply and demand.”

If the demand side of the enrollment equation is treacherous, the supply side is equally charged. Take, for example, faculty resistance to online instruction, a serious obstacle in filling the pipeline of new online courses, a production barrier economists call occupational labor shortage. The obstacle to growth is often not accreditation—which can sometimes be rocky—but dig-your-heels-in faculty opposition to going online. Nearly all schools face faculty resistance, slowing the entrance of new online courses. In an earlier essay in Inside Higher Ed, I called attention to the depths of faculty reluctance.

Looking back to the early days of web-based distance learning, online programs behaved like new start-ups with skyrocketing products. Early-to-market digital courses were not only fulfilling pent-up demand, but with the opening of the digital academic pipeline, streams of new virtual courses flooded learners with entirely new brainy products never accessible before.

At first, socially motivated faculty rushed in, eager to deliver digital classes that promised active-learning benefits—virtual teamwork, peer-to-peer learning and other progressive, constructivist practices. Over the first decades, they tested new teaching and learning methods, spearheading booming growth.

“In the early days,” recalled Karen Pollack, assistant vice provost for online and blended programs at Penn State World Campus, “faculty who went online believed in the transformative power of online learning because it provided greater student access. Early adopters did not see technology as a barrier, but rather as an enabler. Today, very few faculty or administrators ask how they can go online. They are not convinced it’s something they ought to do.”

New courses are now launched with an eye towards preparing students for post-industrial careers in business and STEM fields, with classes introduced less with the intellectually innovative zeal of first movers than with savvy, spread-sheet calculation.

In those early days, online faculty were often sent off into cyberspace with a computer, a passcode and a stack of PowerPoints, with little or no preparation—sink or swim. Today, digital instructors enter their virtual classrooms, not as autonomous teachers, but commonly as part of a team, partnering with instructional designers, videographers and game specialists, among other experts, driving-up the cost of entry.

Schools can no longer waltz into digital education with meager budgets, but must make serious investments to achieve the right balance of high-performance learning technologies with astute virtual pedagogy, aiming to satisfy heightened and more knowing online students. When university financial officers anxiously weigh benefits against risks, inevitably, the digital engine slows.

Supply also retreats when for-profits close and government withdraws its support. Over the last few years, about 100 for-profits fell off the radar in the wake of President Obama’s jaundiced view of predatory, corporate-run higher ed, chopping nearly 3 percent off digital enrollments from the previous year’s results. For example, the University of Phoenix lost nearly 200,000 online enrollments between 2013 and 2016. For-profit retrenchment dealt a damaging blow to online numbers. It’s quite a turnabout when nonprofits come out on top and big corporations suffer serious injury. Sadly, it looks like they may be speeding back under a more cynical administration.

Blended Learning

The surprising news in the digital supply chain is the surge of blended (or hybrid) learning. Offered partly on campus and partly online, blended courses satisfy a fired-up demand for flipped classrooms, low-residency programs, and digital labs and flex delivery. As Joel Hartman, vice president for Information Technologies and Resources at the University of Central Florida (UCF) in Orlando, acknowledges, “Digital education is no longer one thing, but a continuum.”

Take a look at UCF’s chart at the top representing student credit hours, to see where the steam is rising. Just as in the national trend, UCF’s face-to-face (F2F) numbers are falling, but unlike enrollments reported elsewhere, online at UCF is steaming ahead, pretty much paralleling the movement at other large state universities, where growth continues to outperform the rest of the country at more than 13 percent. In what seems like a contradiction, residential numbers have also climbed as on-campus students occupy virtual seats in blended courses.

The hidden news is that UCF’s (and other schools’) dramatically Technicolor bands of rising blended and other courses are buried, not counted in the data released by U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), the nation's primary source of college and university statistics. Nor are they shown in the Babson numbers. By not calculating the contribution of blended, we’re ignoring one of the most significant trends in higher education today.

The UCF chart confirms the quite surprising existence of a quiet revolution in virtual instruction in which blended is penetrating the often hermetic walls of conventional classrooms. As online learning observer Michael Horn notes in Forbes, “Blended delivery of online learning doesn’t count toward the data.”

Students enrolled in blended courses are the undocumented citizens of digital education. As the UCF chart shows, virtual instruction is not huffing and puffing. Blended represents the largely unacknowledged next generation of the academic economy.