You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Don't look now, but the United States appears to have made significant headway in the 2011 academic year toward the goal of significantly increasing the number of degrees and other credentials that colleges award.

This knowledge isn't gleaned from a new study from the federal government; the latest Education Department data that you'll find in that Digest of Education Statistics on your desk (or desktop computer) are from 2008-9.

Nor does it come from any of the blizzard of other reports that dissect postsecondary completion or attainment, such as the annual accounting that the Lumina Foundation released Monday.

Instead, the up-to-date insights come from a new tool -- produced by Nate Johnson, an independent higher education researcher -- that mines preliminary federal data from the 2010-11 academic year to provide a much timelier picture than other studies provide of how many Americans are earning college credentials.

Those data show, among other things, that:

- Colleges and universities in the U.S. awarded 6.5 percent more degrees and certificates in 2010-11 than they did the year before.

- Most of that growth occurred in short-term credentials, with the number of associate degrees climbing by 11 percent and certificates growing by 9.1 percent.

- For-profit colleges led the way in stepping up their awards (12 percent growth over one year, 160 percent growth over the last decade), followed by public and then private nonprofit institutions.

- Eight states (New Mexico, Arkansas, Arizona, Georgia, Virginia, Indiana, Delaware and North Carolina) awarded at least 10 percent more credentials in the 2011 academic year than they did in 2009-10; 10 states produced at least 50 percent more credentials in 2010-11 than in 2001-2.

Johnson laid out his argument for more timely data on college completion in an essay last June in Inside Higher Ed. In it, he wondered how policy makers and educators – who are paying so much attention to college completion as an issue -- can intelligently discuss the topic with years-old federal data that may not reflect current realities, especially in times of economic turbulence.

Take Our Reader Survey

Help us be better. Tell us

what you like (and don't)

about Inside Higher Ed.

Click here to participate.

The most-used national data on degree completion come from the Education Department's Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, and while the agency makes the numbers available about a year after the targeted graduation date (say, August 2011), it is typically a full two years before the numbers appear in the most commonly used federal publications, like the Digest for Education Statistics and the Condition of Education.

Car makers and politicians debating the auto industry bailout have monthly data on auto sales, Johnson said; “[w]ouldn't it be nice to know whether or not there have been any recent changes, perhaps as a result of the economy or of external pressures on colleges, in the mix of vocationally oriented and broader liberal arts degrees awarded around the country?”

But the typical congressman or analyst, Johnson said in an interview, is basing his or her current decisions about higher education policy on information about "students who for the most part enrolled before the great recession."

Johnson's essay (and multiple commenters on it) pointed out the limitations in comparing cars to graduates, and conceded that his proposed solution -- using preliminary data collected by IPEDS, rather than the fully vetted final numbers -- is imperfect. (Historically, changes between the preliminary and final IPEDS numbers have been "modest," he says.) As long as the data are used appropriately, to complement rather than crowd out other statistics, "I remain convinced that the risks of small inaccuracies are outweighed by the need for more timely higher education data," he says.

The other big advantage of the degree completion statistics on which Johnson focuses, he and others say, is that they offer an alternative to the graduation rate data that guide so much of federal and state policy making on the topic of higher education attainment.

Unlike the federal graduation rate data, which focus only on full-time, first-time students, the IPEDS completions file "doesn't disaggregate by the path students took to get the degree -- full time, part time, transfer, etc.," Johnson notes. "It just asks institutions to report credentials awarded." So Johnson's data cover all students, regardless of their enrollment status.

And unlike the attainment data (showing the proportion of Americans with degrees) that the Lumina Foundation reported on Monday, which are slow to move, Johnson describes his "degrees awarded" data as "leading indicators," more timely and measurable. "It's a little like the job creation numbers and the unemployment rate," he says. "Monthly or weekly job creation feeds into the unemployment rate, which moves more slowly and is also affected by the size of the labor force. If we do well on the degrees awarded data, the attainment numbers will probably follow."

Several policy makers who were shown Johnson's data praised the information as a valid and useful contribution to the public discussion. Anthony Carnevale, whose Georgetown Center for Employment and the Workforce is a leading producer of data about postsecondary outcomes, said he liked how "clear and clean" Johnson's numbers were. "Very powerful," he said.

Arthur Hauptman, an independent policy analyst, said he liked Johnson's focus on credentials awarded as a "rough measure of higher ed productivity," which he described as far preferable to the standard emphasis on graduation or completion rates. "Numbers is a better way of doing it than rates," Hauptman said. He said he would very much like to see how the data look for different types of students, so that states and institutions could be assessed on how many of their degrees are awarded to low-income students and other underrepresented groups.

Recession-Driven Growth

The tool that Johnson built (with help from FlatPack Interactive) allows users explore degree completion data from 2002 through the preliminary 2011 numbers, and to break them out by type of degree, state and sector type. (He chose those factors, but the tool could be modified to analyze the data using other criteria, such as student demographics, academic disciplines, etc.)

The data show that American colleges awarded 4.67 million degrees in the 2011 academic year, up 6.5 percent from 2010 (which was in turn 7.2 percent higher than the 2009 total). As seen in the graphic below, growth was fastest (though on a smaller base) for for-profit colleges than for other sectors.

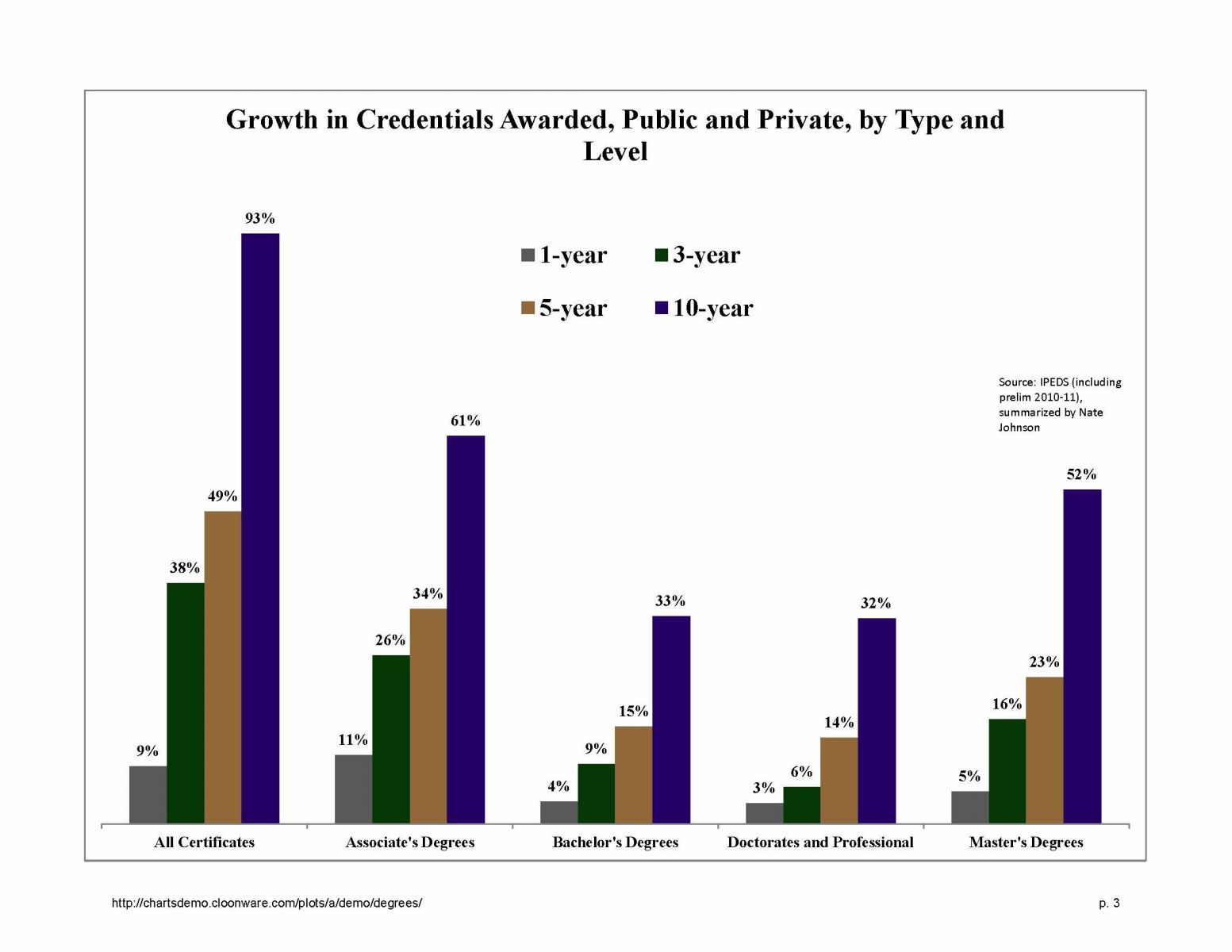

And the awarding of associate degrees grew at a faster clip than did the production of other types of credentials, as seen in this chart:

Johnson cautions that the degrees-awarded numbers -- which, "if sustained, could be sufficient to reach some of the ambitious attainment goals set by policy makers and foundations" -- were almost certainly pumped up by recession-driven decisions by laid-off and underemployed workers to return for more schooling, and are "unlikely to remain" at the levels shown in 2011.

But the data show that colleges have been able to increase their "capacity to award degrees even as public funding for higher education went down," Johnson says. "At least nominally, this represents an increase in efficiency, in terms of dollars spent per degree awarded."