You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The protest movement that started at the University of Missouri at Columbia has outlasted the president of the University of Missouri System, who resigned on Monday. While Missouri had some unique factors, in particular a boycott started by the black members of the football team, campuses nationwide are seeing protests by students over racial tensions without the benefit of support from football teams. Some of the protests are expressions of solidarity with the black students at Missouri, but many go beyond that to talk about racial conditions on their own campuses, which many describe as poor.

The movement is showing up at large campuses and small, elite and not-so-elite institutions, campuses with strong histories of student activism and not. On some campuses the focus is on issues experienced by black students, while on others the discussion is about many minority groups. More protests are planned for this week.

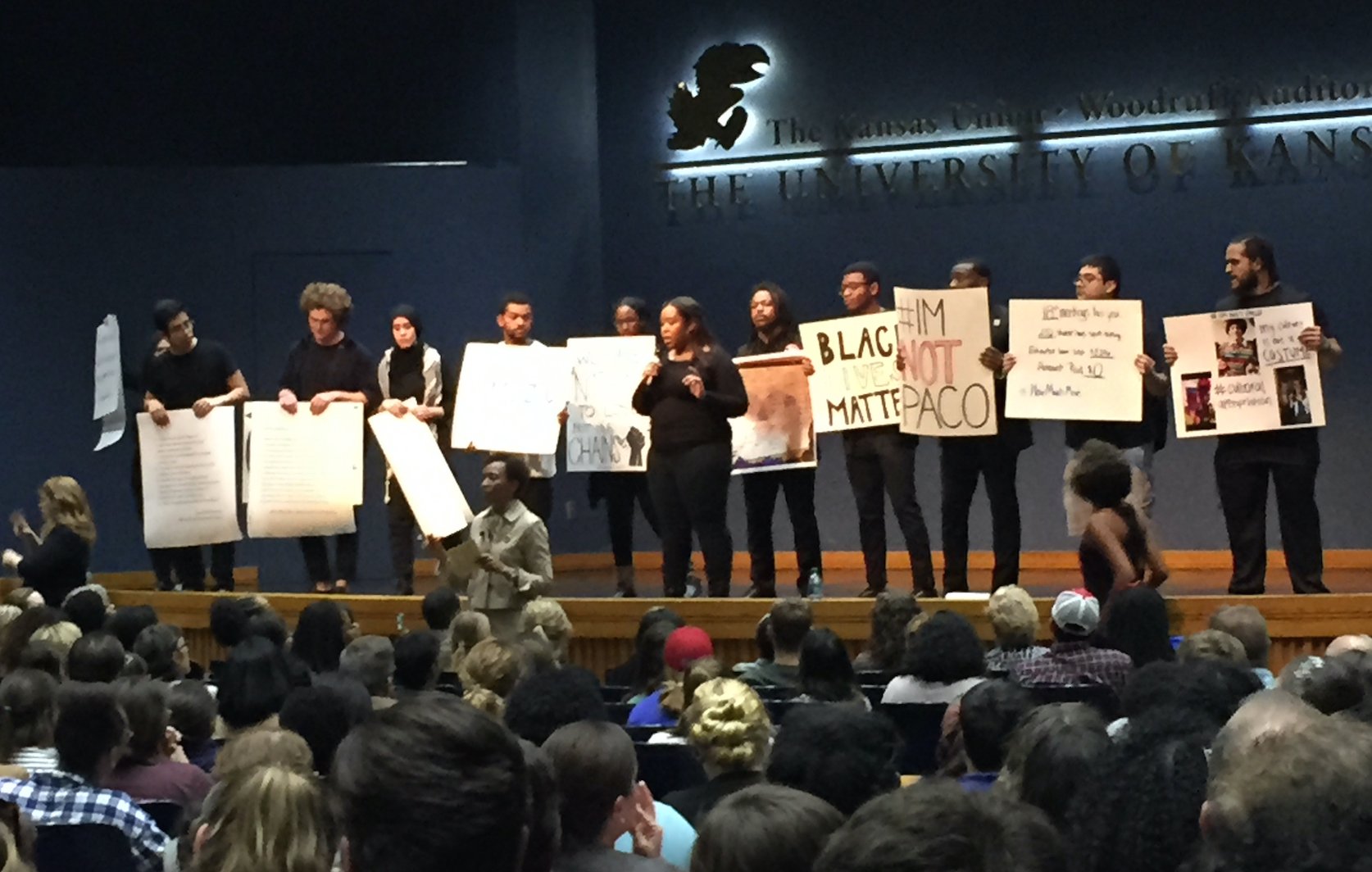

As the weekend ended, students who had been staging a sit-in in the library at Amherst College, with a long list of demands, agreed to leave, despite not getting their demands met. At the University of Kansas, minority students are demanding the resignation of student government leaders who they say haven't done enough for all students, and an alumnus has started a hunger strike on campus -- all on a campus that last week held a lengthy open forum on race relations (right) with the university president, who on Friday issued a statement of support for minority students.

As the weekend ended, students who had been staging a sit-in in the library at Amherst College, with a long list of demands, agreed to leave, despite not getting their demands met. At the University of Kansas, minority students are demanding the resignation of student government leaders who they say haven't done enough for all students, and an alumnus has started a hunger strike on campus -- all on a campus that last week held a lengthy open forum on race relations (right) with the university president, who on Friday issued a statement of support for minority students.

The protests are also provoking considerable backlash -- with online threats appearing at many campuses. While the threats have led to several arrests, without indications that those posting the threats actually intended to carry them out, these actions have caused fear at many campuses.

At Claremont McKenna College, where a dean resigned last week after protests over comments she made that many found offensive, scores of students are circulating a letter saying that the protest movement there -- while motivated by valid concerns -- has gone too far. “It is time for the demonstrations and the hostile rhetoric to stop,” the letter says. The letter also questions tactics, such as hunger strikes, over a dean's statement. “A hunger strike implies that you are willing to die for the cause you strike for …. You ask what the alternative is. It sits in front of you, a petition, a civil and democratic tool. Instead you accuse the dean of not caring about your health and not listening to you when you chose to starve yourself.”

Some online are questioning the veracity of the grievances raised by the protests, with one conservative website publishing a widely distributed article last week suggesting that a swastika made of feces -- one of the incidents cited by black students at Missouri -- could be a "giant hoax." The university has since released a police report that in fact officers found just what students had cited.

The protests are becoming a political issue. President Obama, in an interview with ABC News released this weekend, said that there was "clearly a problem" at the University of Missouri and that he applauded students who engaged in "thoughtful, peaceful" protest. "I want an activist student body," he said. At the same time, President Obama called on activists to spend time listening to those with whom they disagree, and to reject such tactics as trying to block speakers with whom they disagree. "That's a recipe for dogmatism," he said.

Also in the last week, leading candidates for the Democratic and Republican nominations to succeed Obama have weighed in on the protest movement, the Democrats sympathetically and the Republicans critically.

Friday's terrorist attacks in Paris prompted a new wave of charges and countercharges about the protests on American campuses, with some saying that the attacks show how fortunate American students are and many protesting students saying that the tragedy in France has nothing to do with what they have been talking about. On Saturday, the University of Missouri issued a statement to denounce what it called "false social media reports" that people supporting the protest movement were upset that Paris was "diverting media attention."

A more serious backlash has taken place with pundits, many of whom have questioned whether actions by some protest organizers and supporters run counter to freedom of expression.

Amid all of these developments, what exactly is going on? Experts in race relations, student life and campus activism reach no consensus about the protest movement and its meaning. But from discussions with them and the words of protest organizers, some themes emerge:

- Many black and other minority students don't feel welcome and included on predominantly white campuses, and the incidents they are speaking out about are hardly new, but have been going on for some time. Students are speaking out as much about everyday stereotyping they receive (assumptions that they must be athletes, must not be smart, might be dangerous, etc.) as about racial incidents (although there are plenty of them, too). And students aren't just speaking out about stereotyping by fellow students, but by faculty members as well.

- Recent off-campus protest movements -- in particular Black Lives Matter and to some extent the Occupy movement -- have changed the nature of black student organizing on campuses. This isn't just in the use of social media to organize and publicize protests, but a willingness to make demands not with the expectation of getting all (or even most) of them met, but as a way to shift public agendas and to get issues on the agenda.

- Campus presidents matter a lot to many minority students. While the conventional critique of college and university presidents is that they are distant from most students, minority student leaders increasingly expect their campus leaders to be doing more than listening to them at protests, but to be taking public stands and following through with policies that they care about.

- Issues related to free expression, which have come up at some (but not all) of the protests and attracted considerable attention, reflect increasing distrust by many minority students of the press and government institutions.

- A huge question mark of concern to many in higher education is whether the protests will have an impact on the enrollment decisions of today's minority high school students.

Feeling Hostility on a Daily Basis

The various protests -- from Missouri on -- have had a range of prompts and grievances. But experts on minority students point to a common feature that is evident as black students across the country have taken to social media to describe why they are frustrated. They report experiencing constant questions and comments that relate to their race. "When you're the only black student in class & [are] asked, 'are you sure you're in the right class?'" was the way one poster to the #blackoncampus hashtag put it. Or as a Purdue University student stated on a similar hashtag for Purdue students, "When you're told you should consider changing your major because you aren't going to go far." (Students at Purdue rallied Friday, above right.)

The various protests -- from Missouri on -- have had a range of prompts and grievances. But experts on minority students point to a common feature that is evident as black students across the country have taken to social media to describe why they are frustrated. They report experiencing constant questions and comments that relate to their race. "When you're the only black student in class & [are] asked, 'are you sure you're in the right class?'" was the way one poster to the #blackoncampus hashtag put it. Or as a Purdue University student stated on a similar hashtag for Purdue students, "When you're told you should consider changing your major because you aren't going to go far." (Students at Purdue rallied Friday, above right.)

Many other posts relate to what students experience from their roommates and classmates -- questions suggesting that they should speak for all people of their race/ethnicity, questions about growing up in the ghetto (asked of black people who grew up in middle-class neighborhoods but are assumed to be poor), questions about whether they are athletes, as if that's the only way they could have been admitted. And minority students say that they are constantly belittled, sometimes in threatening ways, on Yik Yak, a popular anonymous social media app.

Experts on race relations note that while critics of the protest movement may focus on demands that strike some as excessive, this common frustration is pretty much just a desire to be treated decently. (These complaints are about what some call microaggressions, a term used by many protest supporters and a term mocked by many protest critics.)

Shaun R. Harper, founder and executive director of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at the University of Pennsylvania, does many studies of campus climate.

He said that on campus after campus, he and his colleagues conduct interviews with black and other minority students and find what he calls "onlyness," the feeling of being one or one of a few members of a group, and of being misunderstood and frequently insulted and/or ignored. He said that the interviews he conducts, frequently not at places experiencing the attention and protests of recent weeks, end with students and interviewers in tears, talking about isolation, stereotypes and a lack of inclusiveness. "It's every single time," Harper said.

Harper said he hopes there is "a takeaway" from the recent protests that "people need to finally understand that these issues are very real, and that people experience them much more frequently than they should, and that people are tired of being blown off about these issues."

Beverly Daniel Tatum, president emerita of Spelman College, and author of Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations About Race (Basic Books), said she is sad but not surprised that so many black students on so many campuses report experiencing regular comments that stereotype them. Tatum said that periods of increased diversity in American society create anxiety for many white people, especially in difficult economic times. And that is taking place, she said, at a period in which numerous studies have found that the segregation of neighborhoods and high schools is increasing, not decreasing.

"These comments are all very familiar, and people think it should be different, but the social context is not," Tatum said. "The students showing up on those campuses are coming out of segregated neighborhoods and segregated schools," where they have not necessarily had the chance to have meaningful friendships with people of other races and gotten to know them as individuals. They are more likely to have their views formed "from watching television," and falling into stereotype, she said.

Arthur Levine, president of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, is the co-author of Generation on a Tightrope: A Portrait of Today's College Student (Jossey-Bass), an in-depth look at college students based on research of 5,000 students at 270 colleges between 2006 and 2011. In Tightrope, Levine argued that race relations were improving on campus. The survey research he did, compared to previous surveys, found more students than in the past reporting meaningful friendships with other-race students, more support for interracial dating, and more people thinking that diversity and inclusiveness were important qualities for colleges.

Now, Levine fears, the trend is in the opposite direction. "I think colleges and universities have squandered an excellent opportunity to work on relations among students of different races," he said. The years since 2011 should have seen colleges making a high priority of thinking about how to make colleges more inclusive, but he said he hasn't seen as much of it, and that may explain some of the tensions becoming more evident.

Black Lives Matter and Societal Tensions

Levine also sees campus tensions and protests reflecting changes in American society in the past few years. The constant reports about unarmed young black men being killed by white police officers, he said, change the views of many young people.

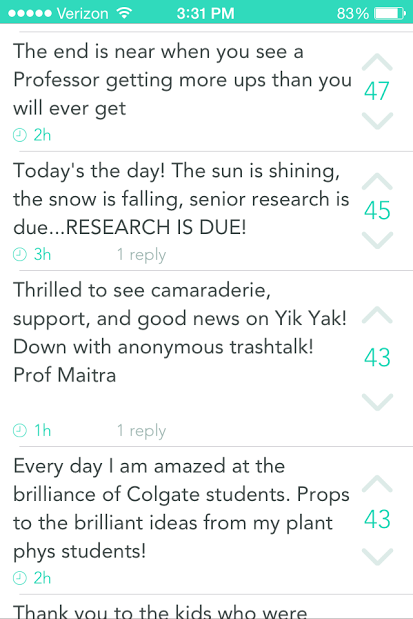

Sean M. Decatur has, as president of Kenyon College, tried to promote inclusivity on his campus. When many campuses were grappling with racist, sexist and homophobic comments posted on Yik Yak, he promoted an approach in which students took to social media with positive messages about a sense of community and respect for diversity.

Sean M. Decatur has, as president of Kenyon College, tried to promote inclusivity on his campus. When many campuses were grappling with racist, sexist and homophobic comments posted on Yik Yak, he promoted an approach in which students took to social media with positive messages about a sense of community and respect for diversity.

On Saturday, he spoke in an interview after a day when spent time with Kenyon students talking about how they might respond to the protests at Missouri and elsewhere. He said students are thoughtful, but many people in American society are perhaps less so.

"In many ways, the past few years have been a pretty divisive time in American culture more broadly, whether you look at it through the lens of issues brought by Ferguson and the Black Lives Matter movement, or larger political polarization that's happening in the country, or the segmentation of conversations due to social media, where people shout at each other."

Eddie Comeaux, associate professor of higher education at the University of California at Riverside, who studies minority college students, among other subjects, said that he believes many minority students are "finding their voices" and also their tactics in the Black Lives Matter movement. The movement showed that students need not have a formal organizational structure or engage in weeks of planning to pull off a protest that will attract attention. And the urgency of the Black Lives Matter message -- sparked by the deaths of young black men -- is inspiring to many students.

Social media makes communication easy, he said, and the protests are building on other protests. Social media also makes it clear to black students who feel alienated on campuses that they are not the only ones with those feelings or a desire for change.

The Buck Stops Where?

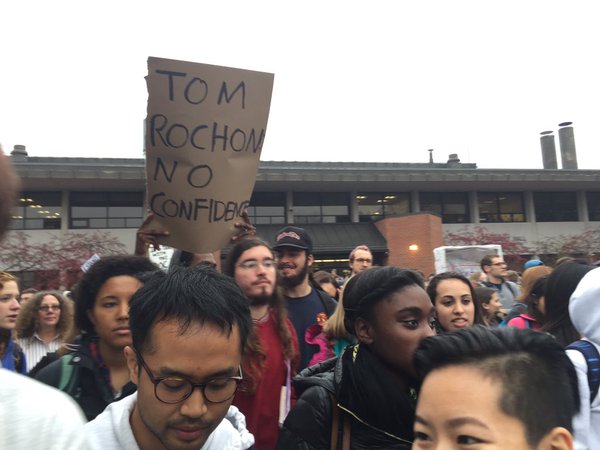

The Missouri protests started with the goal of removing a university system president, Tim Wolfe, who was criticized for not responding to a series of incidents that black students said hindered their educations. The chancellor of the flagship campus at Columbia also resigned his position. At Ithaca College, protests are demanding the ouster of Tom Rochon as president (protest at right). Students and some faculty members accuse him of not doing enough when black students and an alumna experienced racist treatment on campus.

The Missouri protests started with the goal of removing a university system president, Tim Wolfe, who was criticized for not responding to a series of incidents that black students said hindered their educations. The chancellor of the flagship campus at Columbia also resigned his position. At Ithaca College, protests are demanding the ouster of Tom Rochon as president (protest at right). Students and some faculty members accuse him of not doing enough when black students and an alumna experienced racist treatment on campus.

The demands on presidents extend in some cases beyond specific incidents to broad social and historical issues. For example, the students who were sitting in at Amherst's library have as their first demand that "President [Biddy] Martin must issue a statement of apology to students, alumni and former students, faculty, administration and staff who have been victims of several injustices including but not limited to our institutional legacy of white supremacy, colonialism, anti-black racism, anti-Latinx racism, anti-Native American racism, anti-Native/indigenous racism, anti-Asian racism, anti-Middle Eastern racism, heterosexism, cis-sexism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, ableism, mental health stigma and classism."

Angus Johnston, a scholar of student movements who teaches at Hostos Community College and runs the Student Activism blog, said that the pushes for presidential action are in part a reaction to trends in higher education, not just the actions of individual presidents.

"Over the course of the last 30 years or so, we have seen a steady erosion of students' power in the university," he said. So students are frustrated that they feel college leaders don't listen, but many don't have much experience in knowing what presidents can and can't do, or how to ask. "Students are demanding that administrators do things to appease them. If you don't have any experience of having actual power in the university, you have to learn as you go" in negotiations, he said.

"People who are disempowered make symbolic demands," he added.

Presidents have been responding in a variety of ways. Many have been showing up at protests, even when they are criticized while mobile phones record the interactions. Wolfe of Missouri held a series of meetings with those protesting at Missouri before he was ousted, constantly saying that he appreciated the issues that they were raising.

Several presidents, including Rochon, have responded to protests by creating new chief diversity officer positions. Here is Ithaca's announcement of the new position. The University of Missouri System announced the creation of a chief diversity, inclusion and equity officer.

Some student protests at institutions without these positions are demanding their creation. And many chief diversity officers say that they play a key role.

But Levine of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation warned that, in the current environment, presidents can be at risk if they delegate diversity issues and don't stay personally, directly involved, as students are demanding. Making sure that there is someone whose job this is, full time, makes sense, he said. But that doesn't deal with the presidential role.

"At this point, it would be a wonderful thing for presidents to step out and say, 'I think this is a really important issue, and I'm going to take charge of the issue,'" he said.

Harper, of Penn, said that presidents may be engaged in "listening" right now, but that they must move beyond that to taking concrete steps appropriate to their campuses, or they risk losing credibility. And they need to show, he said, "that they are feeling" what students are talking about, not just nodding in a meeting.

Tatum, the president emerita of Spelman, said it may be hard for some presidents to deliver on all the expectations students have for them.

She said, for example, that presidents "don't control everything people on campus say or do," and may not be able to prevent individuals from doing things that cause offense. And she said that presidents have to remember that they must constantly demonstrate their commitments to new groups of students. The students one worked with, and built trust with, a few years ago, graduate and move on, she said, so a new group of students may not remember or care what you have accomplished in the past. And she said that sometimes students "imagine discussions in the back room" (against their interests) that just aren't taking place.

At the same time, she said, presidents do make a difference, and not only with their policies. "The campus leader has to set the tone," she said.

In a statement responding to the Amherst protests Sunday afternoon, Martin said she strongly supports the goals of the protesting students to bring more attention to issues of race and inequity -- and pledged to do more to make Amherst supportive of all students.

But she also said that she could not and should not act by herself on many of the demands. "I explained that the formulation of those demands assumed more authority and control than a president has or should have," she said. "The forms of distributed authority and shared governance that are integral to our educational institutions require consultation and thoughtful collaboration."

Free Speech and the Protest Movement

Several campuses experiencing protests have also seen intense debates over accusations that the protest participants and/or their demands squelch free expression. At Missouri, students and a professor blocked access to a student journalist to protest spaces that were on open areas of a public university's campus. And protest organizers sent out messages on social media questioning whether the press should be there -- even though the protest organized had invited press coverage. The protest movement, under intense criticism, reversed course and encouraged those protesting to be respectful of press rights, and the professor apologized. But many saw Missouri as part of a pattern.

At Yale University, students are demanding the dismissal of an associate master of a residential college (though not necessarily from an instructor role) because she sent out an email questioning whether concern over offensive Halloween costumes had gone too far.

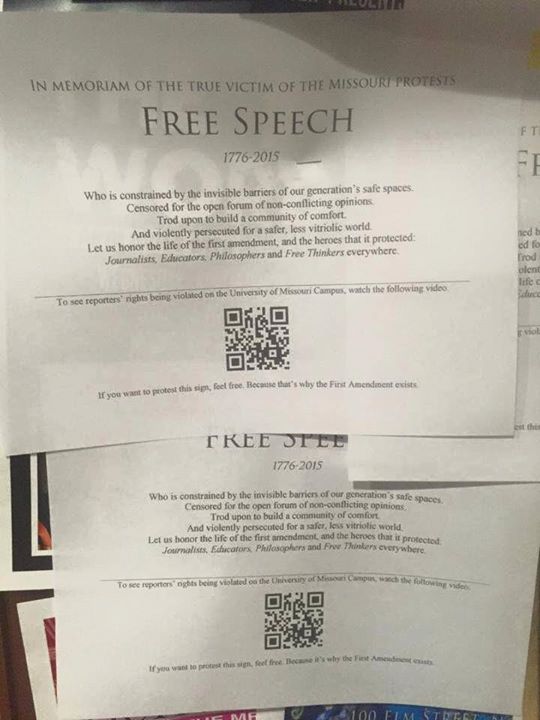

At Amherst, one of the demands of the students who were occupying the library is that President Martin "issue a statement to the Amherst College community at large that states we do not tolerate the actions of student(s) who posted the 'All Lives Matter' posters, and the 'Free Speech' posters that stated that 'in memoriam of the true victim of the Missouri Protests: Free Speech.' Also let the student body know that it was racially insensitive to the students of color on our college campus and beyond who are victim to racial harassment and death threats; alert them that Student Affairs may require them to go through the disciplinary process if a formal complaint is filed, and that they will be required to attend extensive training for racial and cultural competency."

The "All Lives Matter" posters are an example of a response by some critics of Black Lives Matter. And the "Free Speech" poster (at right) was in response to the actions at the University of Missouri (which have since been disavowed).

The "All Lives Matter" posters are an example of a response by some critics of Black Lives Matter. And the "Free Speech" poster (at right) was in response to the actions at the University of Missouri (which have since been disavowed).

The text of the poster that Amherst students want declared unacceptable:

"In memoriam of the true victim of the Missouri protests: Free Speech (1776-2015). Who is constrained by the invisible barriers of our generation's safe spaces. Censored for the open forum of non-conflicting opinions. Trod upon to build a community of comfort. And violently persecuted for a safer, less vitriolic world. Let us honor the life of the First Amendment, and the heroes it protected: Journalists, educators, philosophers and free thinkers everywhere."

Andrew Lindsay, a senior at Amherst and spokesman for the Amherst Uprising, as the movement there is called, said he was aware of but did not agree with the criticism that these demands squelched free expression. He stressed that the group was not saying that those found to have put up such posters should be expelled, only that they go through mediation "so that students can come to a mutual understanding." He said that these posters "really affect the ability of students to be comfortable here." If mediation did not work, he said, then it would be possible for the college to discipline these students.

The various Amherst incidents have brought on much commentary suggesting that the protest movements are hostile to free expression. Amherst students, by protesting a poster called "Free Speech," may have been walking right into that criticism. "Amherst Activists Demand Re-Education for Students Who Celebrated Free Speech," says a headline in The Daily Caller.

But the criticism isn't just coming from the conservative press. The Atlantic is writing about "The New Intolerance of Student Activism." And New York magazine is asking: "Can We Start Taking Political Correctness Seriously Now?"

To observers who are sympathetic with the frustrations of minority students, and their right to protest, the current discussions point both to the need for discussions about language and about the free expression rights of everyone.

Decatur of Kenyon said that as he has watched the debate over free expression, he has become concerned about "the conflation of 'safe space' and 'comfortable space'" in the comments of many people. He says colleges have an obligation to provide the former, but not the latter. By "safe space" (a term much criticized in critical commentary about the recent protests), Decatur said he means "a place where you can express ideas and hear ideas in such a way that you are not going to be attacked personally for who you are," whether that is based on gender, race, sexual orientation or any other factor about a student as an individual.

But just because people shouldn't be attacked for who they are, he said, doesn't mean anyone should get a pass on criticism of the content of their ideas. "Your ideas may be rigorously challenged" and you "may not be comfortable," Decatur said, and that should be fine with college leaders.

Johnston of Hostos said that some of the criticism of student activists over free expression issues seems to him to be one-sided. He said that many, many people have been suggesting that the protest movement pack up and go home, and that such requests are themselves anti-free expression.

Or take the demand that Yale fire an associate master for her controversial email. Johnston noted that she was acting as a student affairs administrator, not a faculty member. He said that she had a First Amendment right to send out her email. But so do students have a right to call for her removal. "I don't believe administrators have a First Amendment right to be freed from student appeals for their dismissal," he said.

As to the Amherst demands, he said some readings do indeed raise free expression concerns -- and this bothers him.

But he said that while it is easy to criticize any denial of free expression, the more difficult question may be to ask why the distrust of journalists and of the benefits of free expression exists.

"It is not surprising to me that student activists of color are more suspicious of the press today than many student activists, white or students of color, have been in the past," he said.

Quite aside from the ethical issues involved, Johnston said that "it's generally not wise to alienate the press."

But he added that "the suspicion that lots of folks have about the intentions of the press and what they can expect is grounded in real-life experience."

Martin, the Amherst president, did not agree to the demands of the protest movement with regard to the signs they find offensive. But she said this about the issue of free speech: "The college also has a foundational and inviolable duty to promote free inquiry and expression, and our commitment to them must be unshakable if we are to remain a college worthy of the name. The commitments to freedom of inquiry and expression and to inclusivity are not mutually exclusive, in principle, but they can and do come into conflict with one another. Honoring both is the challenge we have to meet together, as a community. It is a challenge that all of higher education needs to meet," she said.

"Those who have immediately accused students in Frost [the library] of threatening freedom of speech or of making speech 'the victim' are making hasty judgments. While those accusations are also legitimate forms of free expression, their timing can seem, ironically, to be aimed at inhibiting the speech of those who have struggled and now succeeded in making their stories known on campus. The shredding and removal overnight of protesters’ postings, which were reported to me this morning, is, on the other hand, unacceptable behavior according to the student Honor Code."

What About Next Year's Students?

One of the questions being anxiously asked by those involved in college admissions as these protests have spread is whether they will have an impact on students' decisions on whether and where to enroll.

Harper of Penn said that "this is a real opportunity for minority-serving institutions to help students understand that there are postsecondary options in which they won't be constantly microaggressed, in which expectations won't be low."

But as he said that, Harper said he was uncomfortable with that message for the future freshmen -- not because he doubts the value of minority-serving institutions, but because of the opportunities that are right for some students at predominantly white institutions. "If we go too far in that message" about minority-serving institutions, "it lets predominantly white institutions off the hook and you can just say that you shouldn't bother going to the University of Missouri."

Eli Clarke, director of college counseling at Gonzaga College High School, a Jesuit high school in Washington, D.C., that educates many minority students, said that it may be early to say what impact the protests will have. Right now, he said, seniors are scrambling to finish applications and so it may be a few months, when they are weighing options, that they will focus on the issues raised by the protests.

He said that his minority students ask questions about the issues raised by the protests, but don't use the same language. They are less likely to ask, "Is there a critical mass of black students?" than they are to ask whether someone from the high school, a year or so ahead, applied and enrolled at the college.

And while they don't use terms like "campus climate," Clarke said he gets lots of versions of a question that may not be answered well if students read about the protests. The question students ask him: "Can I find a home there?"