You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In fall 2012, the University of Phoenix soared above other distance education providers. At the time, more than 256,000 students took at least one online course there -- nearly 200,000 more than the next institution on the list. Southern New Hampshire University, by the same metric, ranked 50th.

Three years later, Phoenix still topped the list, but the number of students taking at least one online course there had dropped by nearly 100,000. SNHU, meanwhile, had seen a roughly fivefold increase, climbing 46 spots to No. 4.

The two trajectories illustrate how the distance education landscape changed between fall 2012 and 2015. While many distance education pioneers in the for-profit sector, such as Phoenix, have seen dramatic declines, private nonprofit institutions such as Southern New Hampshire have made significant gains.

But those extremes don’t tell the full story. For while overall college enrollment has declined since the U.S. emerged from the recession following the financial crisis, online enrollment continues to grow across all sectors of higher education, data show.

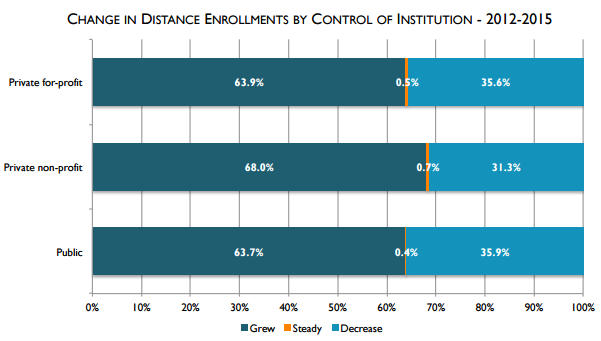

In fact, about two-thirds of all colleges reported that their distance education enrollments grew from 2012 to 2015. The share is highest among private nonprofits (68 percent), but not that much higher than among for-profit (63.9 percent) and public institutions (63.7 percent). And the 3.9 percent year-over-year growth rate reported in fall 2015, the most up-to-date enrollment data available, is the highest observed during that four-year period.

The findings come from Digital Learning Compass, a report analyzing federal higher education enrollment data, produced by the Babson Survey Research Group, e-Literate and the WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies. (For more on the report, see coverage in Inside Digital Learning from April.)

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, said the top-level numbers showing growth across all sectors mask “volatility below the surface.” He pointed to the online enrollment growth at private nonprofit colleges, up 40 percent in 2015 compared to 2012, as one example.

The report doesn’t explore the factors behind the private nonprofit colleges’ success in the online education marketplace (though the Babson Survey Research Group plans to do follow-up reports this year), but Seaman floated two hypotheses: it could be that those colleges are benefiting from large for-profit colleges losing students, he suggested, or that the private colleges’ online programs are just now reaching a point where the institutions are able to enroll a large number of students.

Pete Boyle, vice president of public affairs for the National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, said in an email that he believes both hypotheses have had an impact, but that he leans toward the latter -- that online programs have matured.

“A key part of that maturation would be how to make online pedagogically sound,” Boyle said. “One could argue that for-profits jumped in with not enough substance, while private nonprofits focused on the substance first. Institutions developed programs that had pedagogies that faculty could incorporate into the regular curriculum/mission of the institution. So, there was a maturation in that sense.”

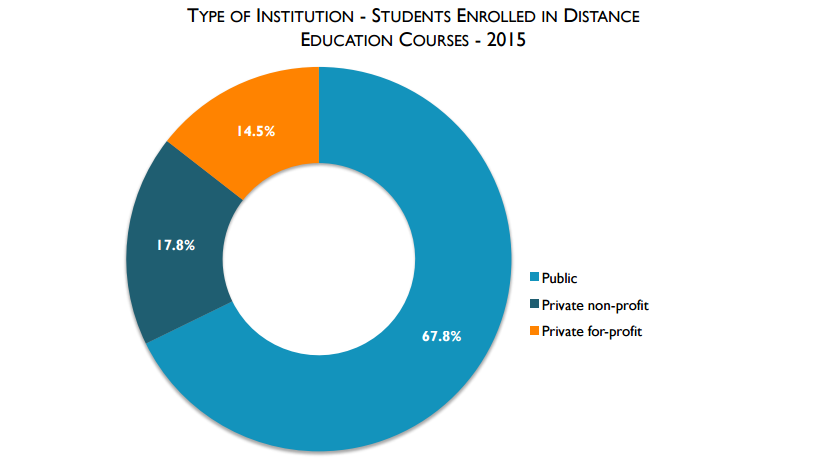

The enrollment growth at private nonprofit colleges means the sector has passed for-profit colleges as the second-largest in the distance education market. Public institutions still teach the majority of online students: 67.8 percent, according to the 2015 data. Of the six million who studied online in fall 2015, 4.1 million attended public institutions, one million private nonprofit colleges and about 871,000 for-profit institutions.

The findings also challenge the narrative that the for-profit sector, broadly, is in decline. While online enrollments at most of the institutions in that sector grew in the 2012-15 time frame, the growth was erased by declines at institutions such as Phoenix and Ashford University, both of which have faced scrutiny from the federal government.

Over all, the for-profit sector lost 191,300 online students from fall 2012 to 2015. While the government won't release the next batch of enrollment data until next year, estimates suggest the for-profit sector has continued to shrink.

Steve Gunderson, president and CEO of Career Education Colleges and Universities, a trade group representing for-profit colleges, said the sector “grew too much too fast” when it attempted to capitalize on increased interest in higher education during the recession. “We had terrible outcomes, and we paid a price for that,” he said.

Gunderson said the for-profit sector will be better off if it focuses on training students for careers rather than competing with other types of colleges to offer “online liberal arts education.” CECU last year changed its name from the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities to emphasize that focus. Before APSCU, the organization was known as the Career College Association.

“Any kind of civil war between the different sectors is an absolute waste of time and energy,” Gunderson said. “There is more demand than any one of our sectors is going to be able to meet on its own.”