You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

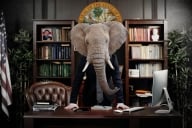

Paul Chan

At Grinnell College, an unexpected and contentious fight has emerged between administrators of a proudly progressive institution and the country's only independent union of undergraduate student workers.

The case at Grinnell could have lasting implications, as officials plan to appeal an expansion of the union to a federal board -- its decision could affect whether other, similar units would be allowed to take shape.

Leaders of the college did not block the Union of Grinnell Student Dining Workers from forming in spring 2016, when, as the name suggests, the union only represented the institution’s student dining hall employees. The group was a grassroots effort with no affiliation with another union, and it lacked legal support, with the organizers relying on materials on the National Labor Relations Board website during its creation.

The college published a glowing news story in December 2016, after administrators and the union signed a one-year contract that raised wages for the dining hall workers from $8.50 to $9.25 an hour (their hourly pay has since reached $9.76). Officials trumpeted that the agreement between an independent student union and a private college was the first of its kind. Kate Walker, vice president for finance and treasurer of the college, in a statement called it a “win-win” that would benefit the students and attract new dining hall applicants for the college.

But the relationship soured after September 2017, when the union announced a campaign to triple the size of the unit by including all undergraduate workers -- the institution employs more than 700 student workers. In addition to the dining hall, students work at the Grinnell library, in college housing and the career center, among other places.

At least as far back as November 2017, administrators began hinting they would not back the union expansion. The union posted a statement then that its members learned the administration would oppose it expanding beyond the dining services and catering. Administrators said that the student workers should be considered students first, not employees.

“The message is clear: Grinnell is prepared to fight to stop students from organizing for fair wages and working conditions,” the union said in its statement.

In April, President Raynard Kington published a memo detailing his opposition. His argument: dining work was not bound to “the educational mission” of the college, but other positions were. The jobs were so diverse that a single union couldn’t adequately represent them all.

“If dozens of unions were formed to cover each of the groups of student positions that are related, it would be unduly burdensome and expensive to administer such a system,” Kington wrote. “The resources spent doing so would necessarily be drawn from the mission of the college. This could have an adverse impact on our students who receive financial aid through the work-study program. And given the need to reallocate budget to cover increased costs, other benefits to the student experience would be compromised.”

About $2 million, or 2 percent of the institution’s expenses, go toward student pay, according to filings with the NLRB.

In October, the union filed a petition to have a student vote on an expanded union with the NLRB, which a regional official of the board approved for a vote Nov. 27. The college railed against the concept of an election, hiring two separate law firms, Nyemaster Goode and Proskauer Rose, known for being hired by employers fighting unions. Proskauer Rose has represented all of the professional sports leagues, including the National Basketball Association and the National Football League, during lockouts and other major negotiations.

Columbia University also hired the firm when it was battling against the formation of a graduate student union.

Prior to the vote, Grinnell requested that the NLRB stay the election or impound the ballots.

The college was unsuccessful.

In the election, the union earned 274 votes in favor of the expansion, with 54 against.

The college has laid out a frequently asked questions page online on why it disagrees with the expansion and has publicly stated it intends to appeal the election.

Grinnell said that expansion “harms the core mission” and impedes trust between professors and students.

“Expanding the union could effectively insert a third party whose priorities are economic, not educational, into learning outside of the classroom and alter the relationship between students and faculty,” the college wrote.

Officials also expressed concerns about federal privacy laws and disclosing financial information about other students to the union leaders.

“Given our values, it might seem that unionization of all student positions would fit naturally into Grinnell’s culture,” it wrote. “In reality, this expansion of the union would undermine the college’s ability to pursue its core educational mission and maintain its distinctive culture, where co-curricular, individually advised learning plays an important role.”

The college has not yet officially appealed yet. But the union has filed several complaints with the NLRB, including accusing the college and the Board of Trustees of intimidation and coercion.

Should the college succeed in its appeal with the Republican-controlled NLRB, the decision could prove influential at institutions across the country. In 2016, when the labor board was under Democratic watch, it ruled that Columbia’s graduate student assistants served as employees, which had allowed them to unionize. While opponents of graduate student unionization have also made the case that student work is part of an educational program, the NLRB declared that someone could both be a student and employee, and the work of graduate teaching assistants is arguably much closer to an institution's educational mission than the jobs that most undergraduates hold. (Student employees at public universities have their unionization rights governed by state laws.)

Andy Pavey, a first-year student and press secretary for the union, said its members are worried about the outcome of the decision. The expansion is necessary for all students because tuition has vastly outpaced wages offered on campus, Pavey said. The union would also like to institute a formal grievance process for students who have been fired and secure at least unpaid medical leave.

The pending appeal means that officials have refused to negotiate with the union outside the dining hall workers.

Because they’re just students, they don’t have the finances to hire a lawyer or pursue a lawsuit in the event that the appeal doesn’t go their way, Pavey said -- if someone were willing to work pro bono on their case, they would “really appreciate it.”

“We’re certainly concerned about national ramifications. If the college thinks it can scare us just by invoking this Trump board, they’re wrong,” Pavey said. “The battle for student workers is across the entire country, and we know that the labor community is keeping a close eye on this, and don’t want to jeopardize it. We’re going to continue to fight for the time being.”

Some alumni have also signaled their support for the union, writing to The Des Moines Register that unionization is a pillar of a healthy democracy and that the college should not appeal to the Trump-appointed NLRB.

“Grinnell students should be the ones to decide if they want to unionize,” the alumni wrote. “They have the right to a fair election, and to have the results of that election respected by their employer. If Grinnell College truly cares about social justice, it will respect its students, their election and the results.”