You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Democratic vice presidential nominee Senator Kamala Harris (back to camera) listens as the Florida Memorial University marching band plays during a campaign stop in Miami Gardens, Fla. Harris talked about the Democratic free college proposal.

Getty Images North America

Campaigning at Florida Memorial University last week, Democratic vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris emphasized the importance of going to college, including historically Black colleges and universities like the one where she was speaking.

“It is the place where we nurture young people to see who they are and their role as part of leadership of our nation in whatever profession they choose,” she said.

And she said that she and Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden would make going to college free for most students.

That went over well, because what’s not to like about free, right?

But less than two months before the election, one of the divisions between Biden and his Republican opponent, President Donald Trump, is over the Democratic plan to make attendance free at two-year colleges, as well as for those whose families make less than $125,000 at public four-year colleges, as well as public and private HBCUs.

There’s also the hundreds of billions of dollars that it would cost over the next decade.

“The reality of Biden’s ‘free college’ plan is that it’s anything but free, and he and his campaign should explain to the American people what the total cost of their socialist plan is and how they expect to pay for it,” Trump campaign spokeswoman Courtney Parella said in a statement to Inside Higher Ed.

To conservatives, including education experts at the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise Institute, the idea of making college free is akin to those offers on TV for free cellphone service or interest-free car payments.

In the fine print, they argue, are a host of problems, from it being unfair to make those who didn’t go to college have to pay more for others to get higher education to government stifling conservative thought on campuses, and inadequately funded institutions reducing the number of students who can go to college. Though little talked-about on the campaign trail as the focus turns to the pandemic, conservative fears about free college have come up at times.

“Free college may sound nice, but the outcomes would be anything but nice,” warned U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos during a campaign appearance for President Trump near Harrisburg, Pa., in February.

“Think about it,” she told cheering supporters of Trump, who does well with those who did not graduate from college. “Only a third of Americans pursue four-year college degrees. Why should two-thirds pay for the other one-third?”

Despite the rhetoric, though, some recent polls call into question how widely opposed Republicans are to the idea of free college, as well as how strongly Democrats really feel about bringing it about.

On the surface, Americans are divided over the issue, as they are about many things these days, on partisan grounds.

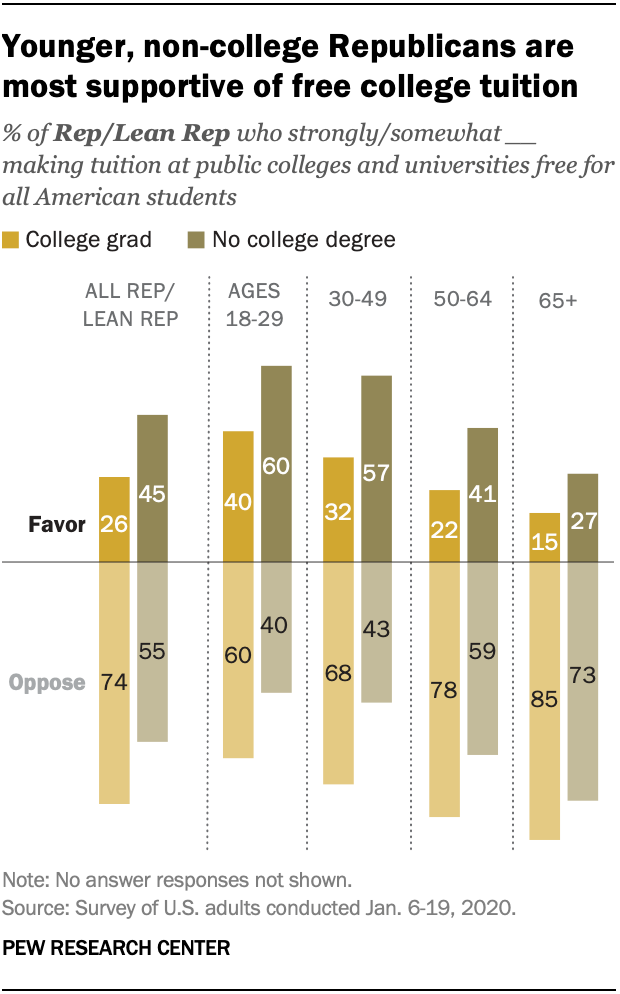

A Pew Research Center poll in January found 83 percent of those who identified themselves as Democrats or leaning Democratic supported making tuition free, compared to only 39 percent of Republicans and those leaning Republican.

However, it found the idea has support among some Republicans: younger people, women and, somewhat surprisingly, those same people without college degrees DeVos was trying to rile up.

The Pew poll found that among Republicans between 18 and 29 years old, a majority, 55 percent, supported making tuition free.

Those between 30 and 49 were generally split, with 48 percent supporting the idea and 52 percent opposed.

Republicans older than 65, though, are deeply opposed to making college free, with only 24 percent in support and 76 percent opposed.

Similarly, the poll found a difference based on gender. Two-thirds of Republican men were opposed to free college. But Republican women were more open to the idea, with 47 percent in favor and 53 percent opposed.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the Pew poll found that the idea of free college is more popular among Republicans without a postsecondary degree than those who did graduate from college.

Forty-five percent of Republicans who did not graduate from college, according to the poll, supported free tuition, compared to 26 percent of Republican college graduates.

Most starkly, 58 percent of Republicans younger than 50 who have not completed college supported the free college idea, compared to 34 percent of Republican in the same age group who did graduate college.

"Wow, I'm very surprised by that finding," said Mary Clare Amselem, an education policy analyst at the conservative Heritage Foundation. She guessed that people who went to college left with a decreased sense of its value and therefore don't see the value in a large-scale government investment.

Ben Miller, vice president for postsecondary education policy at the liberal Center for American Progress, said he wasn’t surprised "that someone who might benefit from that proposal based on their age or education might be more supportive of it than someone who already has been through college and doesn’t want to ensure that others might be able to get a financial deal similar to what they received some time ago."

Older Republicans may not realize how out of hand the cost of going to college has become, he said. “It’s the exact same problem you see with the ‘when I went to college 30 years ago, I worked my way through so why can’t people today’ argument. The societal deal we had decades ago doesn’t exist anymore, and a lot of those folks are out of touch,” Miller said.

But while free college is popular with the Democratic Party’s left wing, polls also raise questions about how strongly Democrats as a whole feel about the idea, particularly as the pandemic has shifted attention to other issues even in higher education.

The Pew study found that 92 percent of those who supported Vermont Independent senator Bernie Sanders in the Democratic presidential primary, and 88 percent of those who supported Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren, say they favor making tuition free.

And two-thirds of Sanders supporters and 54 percent of Warren supporters said they feel strongly about it.

But while 76 percent of Biden supporters said they support the concept of free college, only 42 percent felt strongly about it. Over all, only about half of all Democrats polled felt strongly about making college free.

A poll in June by the centrist think tank Third Way had similar findings. While 75 percent of Democrats said they support free college, only half said it was a top priority in higher education.

Over all, the Third Way poll found that only 36 percent of those surveyed from both parties said making college free is a top priority in higher education.

Among the 10 other goals more often seen as a top priority were the 63 percent -- including 90 percent of Democrats and 83 percent of Republicans -- who said higher education should be more affordable, though not necessarily free.

Those who listed that as a top priority were concerned about pressing questions now, like whether students should pay as much for online courses as they were supposed to pay in person, said Tamara Hiler, Third Way’s education policy director.

“Other things feel more pressing these days. The No. 1 issue we’re hearing about is health and safety and the process of reopening. At the end of the day, people don’t think they shouldn’t have to pay anything, but they want to make sure it’s fair,” she said. More, 61 percent said protecting student loan borrowers from predatory colleges is a top priority right now.

Wesley Whistle, senior adviser for policy and strategy at the left-leaning New America, is among those dubious about whether free college is a top priority. A more pressing issue, he said, is improving K-12 education “so we can make sure people can get to college in the first place.”

To conservatives, though, their concerns about free college go beyond how high a priority it is. Critics like Jason Delisle, a higher education financing expert and a resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, say making college free ignores the real problem behind unaffordable colleges. And then there’s the cost.

A study last week by Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce, and Jenna Sablan, a former assistant research professor at the center, estimated that the free college plan would cost $49.6 billion in the first year, with $33.1 billion covered by the federal government and $16.5 billion by the states. Over 10 years, it would cost the federal government and states $683.1 billion.

To Carnevale and Sablan, though, the benefits outweigh the cost. They estimated that undergraduate enrollment could increase by 4 to 8 percent overall, and by 6 to 14 percent at public colleges.

“Making public colleges and universities tuition-free would likely motivate more students -- especially those who once thought college was too expensive -- to attend their local or state college,” they wrote. “At the same time, students who were attending a selective private university might realize that they can get a similar education for free at their state’s flagship university.”

Their study estimated that more students getting college credentials would also mean that more would get higher-paying jobs, generating $371.4 billion in more taxes over a decade. Sablan, in an interview, said the jobs requiring a college degree are expected to return faster than those that do not as the economy improves.

And by the 10th year, they wrote, the increase in tax revenue every year should surpass the annual cost of making college free.

“Free college isn’t really free,” they wrote. “But its value will start to outweigh its costs within a decade.”

While DeVos at the campaign appearance in Pennsylvania appeared to be playing to those Trump supporters who did not go to college, a University of Pennsylvania analysis on Monday called into question how many of those with only a high school degree would really be paying for others to go to college for free under Biden’s plan.

According to the Penn Wharton Budget Model, Biden’s entire campaign platform would require $3.375 trillion in additional tax revenue over the next decade, but 80 percent would be paid by those in the top 1 percent of incomes.

Those making less than $400,000 a year in Biden's plan would not see their taxes rise, according to the study. But they would see their returns on their investments decline because of the corporate tax increases for which Biden is calling.

Ultimately, the study said, those making less than $400,000 would see their after-tax income decline by a little less than 1 percent under Biden’s plans, while those making more would see a decline of about 18 percent.

Certainly those who will be getting a higher education will benefit from free colleges, said Jessica Thompson, associate vice president at the left-of-center Institute for College Access and Success and a supporter of the idea. “But there’s significant societal value” in more people going to college, she said.

“Increasing education levels helps everyone, not just those who go,” said Miller. Studies have shown that increasing the number of college graduates in an area raises wages for everyone in that area.

And, Miller said, “If you’re worried about higher education being perceived as elitist, making it something everyone can afford while ensuring you deal with capacity constraints is the way to go. I’d also note that everyone making the elitist or ‘not everyone should go to college’ argument themselves is a college graduate, often multiple times over.”

But conservatives say they’re also concerned about more government control. “There’s definitely a concern about more politically motivated teaching on campuses,” said Amselem, of the Heritage Foundation.

“There’s a significant left-leaning bias in colleges, where diversity of thought is not only not welcome. It’s heavily discouraged,” she said. “The problem is that if someone is hearing only one type of thought, they will go into the world never having been confronted with ideas that disagree with them.”

However, free college supporters discount the fear. “It seems like a red herring,” said TICAS’s Thompson. Sablan said there could be more strings that come with federal funding, but among policy experts, discussions about what sort of requirements could be imposed do not have to do with curriculum. Rather, she expects more accountability measures about how often students get degrees and what sorts of jobs they can get with their degrees.

“The only proposal I can recall that addresses what colleges teach is the president trying to go after the 1619 Project,” Miller said, in reference to Trump’s threats to defund K-12 schools that use The New York Times’ project on slavery in lessons.

To proponents of free colleges, tuition has skyrocketed around the country because of cuts in state higher education funding for colleges, particularly since the last recession a decade ago. The Biden plan would try to spur more state funding by requiring that states pay for one-third of the cost of eliminating tuition, while the federal government pays the other two-thirds.

However, critics like Delisle warn that the public colleges and HBCUs would then be reliant on government funding, because the colleges would no longer have the option to increase revenue by raising tuition, as they did when state funding decreased.

In some European countries, like Britain, France and Germany, colleges found themselves underfunded and reduced the number of students they let in, Delisle and Amsalem said.

“Democrats like to say the federal government and state governments aren’t adequately funding universities. Free college and federally mandated price caps doesn’t change that,” said Delisle.

Because private colleges would still be able to raise tuition to generate more money, while public colleges falter, Anselm worried it would create a two-tiered system. Those who can afford it would pay to go to better-resourced private colleges, while others would have to go to publics. And if those colleges cut back on admissions, fewer students could end up being able to go to college, even if it is free.

“They’re the types of unintended consequences that sort of get glazed over,” Anselm said.

Supporters like Thompson acknowledge that some states may not come up with their one-third of the cost at a time when many are cutting budgets during the recession. While the Biden plan does not include the idea, Thompson and others like Miller said any free college plan should include a commitment by the federal government to pay more than the two-thirds of the cost when states are struggling financially.

Further, to Delisle, free tuition wouldn’t address the real problem behind the rising costs to attend college, or the increase that’s driving the amount of debt students are having to take on.

True, tuition increased at public universities from $3,000 in the mid-1990s to $8,000 in the 2015-16 school year, he wrote in a paper in May.

But financial aid also increased during that time. For Pell Grant recipients, tuition after the aid was factored in rose only by $543, to $1,100 over that period.

What has risen sharply, he said, are living expenses, perhaps because of changing needs like childcare for older students. “The trend may be the result of the so-called ‘amenities arms race’ and rising expectations among students for high-end facilities such as dormitories, recreation centers, and dining facilities,” Delisle wrote.

To Thompson, a key to Biden’s plan is that it would also double the size of Pell Grants to help cover living costs.

But to Delisle, the free college plan goes too far. All that's needed are incremental changes like increasing student aid, instead of “the radical transformation envisioned in the free-college proposals.”