Free Download

Provosts are generally confident of free speech rights at their own colleges and universities, but many are worried about the situation more broadly in higher education, according to the 2018 Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Chief Academic Officers, conducted by Gallup and answered by 516 provosts or chief academic officers.

The survey comes at a time of intense debate in higher education and in American society over whether colleges and their students respect the principles of free speech. The survey also comes after a year in which many faculty members -- many of them relatively junior in their careers and members of minority groups -- found themselves under attack. A majority of provosts believe that conservative politicians and websites are unfairly condemning these professors.

Other highlights of the survey include:

- Most provosts believe that the academic health of their institutions remains strong; that level of confidence hasn't changed much in recent years.

- Chief academic officers are strong supporters of the liberal arts, but many are pessimistic about the future of liberal arts programs and liberal arts colleges.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2018 Survey of College and University Chief Academic Officers was conducted in conjunction with researchers from Gallup. Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Thursday, Feb. 22, at 2 p.m. Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Register for the webcast here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Chief Academic Officers was made possible in part with support from Jenzabar, Macmillan Learning, Portfolium, VitalSource and Wiley.

- Most CAOs believe their institutions are working hard to promote civic engagement and civil discourse on their campuses. But most also say this is harder because of the current political climate.

- While a majority of provosts believe that students of all political views feel welcome in classrooms, they are more likely to say that about liberal students and white students.

- Most provosts believe that faculty members should not profit from assigning their own textbooks, but only a minority of colleges ban the practice.

- More provosts than in the past see value in competency-based education, but support remains stronger in public than in private higher education.

Free Speech and Academic Freedom

The last academic year has seen a national debate over free speech on campus, set off by the shouting down of Charles Murray by students at Middlebury College in March (at right), but extending to many other incidents, involving such speakers as Milo Yiannopoulos, the conservative pundit, and Richard Spencer, the white supremacist. Many inside and outside academe have questioned whether colleges have appropriately stressed the value of free expression.

The last academic year has seen a national debate over free speech on campus, set off by the shouting down of Charles Murray by students at Middlebury College in March (at right), but extending to many other incidents, involving such speakers as Milo Yiannopoulos, the conservative pundit, and Richard Spencer, the white supremacist. Many inside and outside academe have questioned whether colleges have appropriately stressed the value of free expression.

In general provosts said that they believed principles of free expression -- related to speaking invitations and respect for speakers -- were solid on their campuses. But as the data below show, significant minorities of provosts had doubts about whether invitations were being extended across the political spectrum. And provosts were nearly uniformly confident of the respect that would be accorded to liberal speakers, but not quite as certain about the respect accorded to conservative speakers.

While provosts were generally supportive of free speech rights, they were divided on the question of whether colleges should ever interfere in invitations extended to speakers.

(Note: On tables that follow, those expressing neutral views are not included, so the figures don't add up to 100 percent.)

Provosts’ Attitudes on Free Speech and Campus Speakers

| Statement | % Public Provosts Agreeing | % Public Provosts Disagreeing | % Private Provosts Agreeing | % Private Provosts Disagreeing |

| My campus hosts speakers representing a range of political viewpoints. | 55% | 22% | 57% | 21% |

| Conservative academics and public figures are treated with respect when they visit my campus. | 90% | 8% | 79% | 5% |

| Liberal academics and public figures are treated with respect when they visit my campus. | 89% | 2% | 87% | 1% |

| Students on my campus generally respect free speech rights. | 77% | 5% | 75% | 3% |

| Faculty members on my campus generally respect free speech rights. | 82% | 3% | 90% | 2% |

| Colleges should not interfere with invitations to outside speakers extended by students groups or faculty members. | 35% | 36% | 20% | 48% |

Provosts in the survey were much more confident of the security of free speech on their own campuses than they were about its status in higher education as a whole.

On their own campuses, 19 percent of provosts said free speech was very secure, and 61 percent said it was secure. Only 19 percent said it was threatened, and only 1 percent said it was very threatened. But asked about college campuses generally, 51 percent said that free speech was threatened, and 8 percent said it was very threatened.

The responses in some ways follow previous patterns in surveys of provosts (and presidents and business officers, for that matter), in which they are more likely to see a range of problems in higher education generally than at their own institutions.

One area of debate nationally -- and of disagreement among provosts -- involves removing students from events they are disrupting, and punishing those who disrupt. One theme of criticism of higher education over the free speech issue is that colleges have not taken action in response to violations of free speech. In fact, Middlebury did punish those who disrupted the Murray speech, and Claremont McKenna College punished students who disrupted a talk there. (In both cases, the colleges were criticized by some for not being severe enough and by others for imposing any punishments at all.)

A majority of the provosts (55 percent) surveyed said that colleges should try to remove those who disrupt speakers, but only a minority (31 percent) said such students should be punished, with the same percentage saying they shouldn't be punished.

The Academic Freedom of Professors

Discussion of freedom of expression in higher education in the last year was not limited to the speech of students or the speakers they invite to campus. A series of incidents featured faculty members -- many of them not white, many of them people who commented on white privilege or racism -- coming under attack.

Discussion of freedom of expression in higher education in the last year was not limited to the speech of students or the speakers they invite to campus. A series of incidents featured faculty members -- many of them not white, many of them people who commented on white privilege or racism -- coming under attack.

In numerous cases, these attacks were set off by professors' comments on social media, many times comments they assumed would be read by fellow academics, not conservative pundits looking to mock academe. In several cases, faculty members have been suspended or lost their jobs over these statements -- even as they have argued that their views have been distorted.

Many faculty groups have faulted college leaders for not doing enough to protect these academics.

This year's survey of provosts found that many chief academic officers see an increase in attacks on academics -- and the administrative leaders aren't sure academe had done enough to defend their academic freedom.

Nationally, 59 percent of provosts believe that academics are being "unfairly attacked" by conservative websites and politicians. And 29 percent said that those attacks included professors at their own institutions. The share agreeing with that statement was lowest at community colleges, 19 percent.

A substantial minority of provosts (36 percent) said they fear that professors at their own institutions could become targets of campaigns against their ideas.

While provosts clearly are concerned about the academic freedom issues involved, a majority of them also see some communication problems at play.

Asked to respond to the statement "Professors sometimes do not pay enough attention to how their ideas may be understood or misunderstood on social media," 83 percent of provosts agreed.

Civic Engagement and Campus Culture

Amid numerous ugly incidents on campus -- speakers being shouted down, racist videos or posters put up, to cite but two examples -- many have wondered if enough attention is being paid to making campus culture inclusive and promoting civic engagement.

Amid numerous ugly incidents on campus -- speakers being shouted down, racist videos or posters put up, to cite but two examples -- many have wondered if enough attention is being paid to making campus culture inclusive and promoting civic engagement.

A majority of provosts at both public and private institutions value civic engagement and inclusiveness. But on civic engagement, those at private institutions appear more confident that they have programs to engage students and that those programs are making a difference. One area where provosts of public and private institutions agree is that the current political environment makes it more difficult to promote civic engagement and civil discourse on campus.

| Statement | % Public Provosts Agreeing | % Private Provosts Agreeing |

| My college actively works to promote civic engagement among students. | 76% | 88% |

| My college is successful in ensuring civic engagement among most students. | 59% | 71% |

| My college actively works to promote civil discourse by students. | 66% | 81% |

| My college is successful in ensuring civil discourse among most students. | 52% | 68% |

| Efforts to promote civic engagement and civil discourse are made more difficult by the national political environment. | 88% | 85% |

And what about civil discourse and inclusiveness in the college classroom? Many critics of higher education on the right say conservative students are not made to feel welcome in the classroom, and many on the left say minority students are not made to feel welcome. The findings of the survey suggest that provosts are generally confident of the level of inclusiveness in their classrooms, but less so for minority students.

Asked about conservative students, 68 percent said that such students "generally feel welcome" in classrooms on their campuses, while 11 percent disagreed. There was a bit more confidence with regard to the comfort of liberal students. Only 3 percent disagreed that they were comfortable on their campuses.

But turn to race and ethnicity and the picture is a bit different. Most provosts agree that white students (94 percent) and minority students (70 percent) are comfortable in their classrooms. But beyond the gap in the percentage agreeing, there is a large gap in those strongly agreeing. Of provosts, 48 percent strongly agree that white students feel comfortable in their classrooms. The figure drops to 22 percent when asked about minority students.

Academic Health

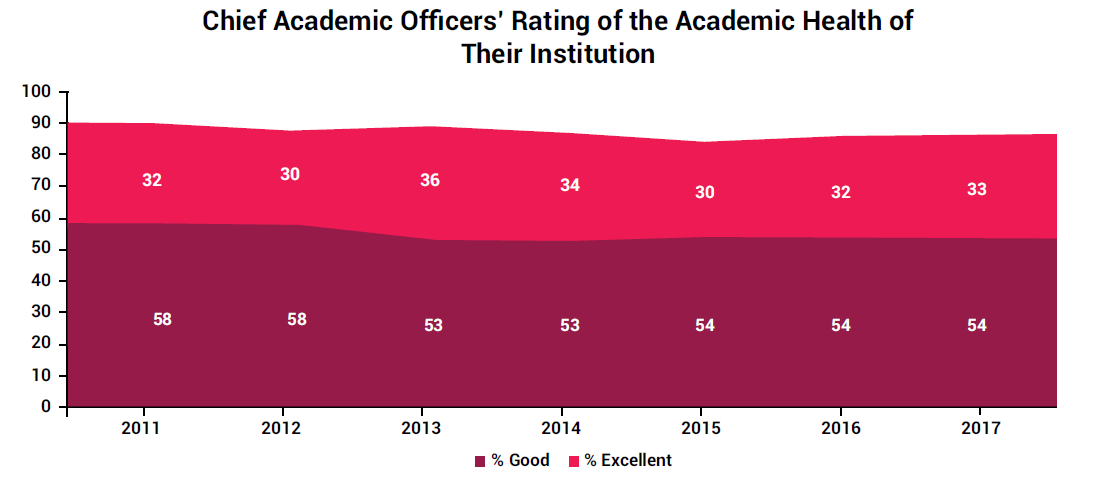

Most provosts rate the academic quality of their institutions as good or excellent, and have done so for a number of years now.

Very few provosts found that the academic health at their institutions was either fair (10 percent), poor (2 percent) or failing (less than 1 percent).

Continuing a pattern from recent years, most provosts (69 percent) said that their institutions were "very effective" in providing a quality undergraduate education. But the shares saying that their institutions were very effective in certain categories of providing an undergraduate education were quite a bit lower.

Only 48 percent said their institutions were very effective in preparing students for the world of work, only 45 percent saw their institutions as very effective in providing undergraduate support services, and only 29 percent said that their institutions were very effective in using data to inform campus decision making.

And in a category of great importance to tuition-paying students and their parents, only 28 percent of provosts believe that they are very effective at controlling rising prices.

The Liberal Arts

The year 2017 saw increased anxiety among supporters of the liberal arts, many of whom feel that liberal arts colleges and departments are in danger.

Provosts are strong supporters of liberal arts education, but that doesn't mean that they are optimistic about the future of the disciplines.

Nearly two-thirds of provosts (63 percent) strongly agree that "liberal arts is central to undergraduate education -- even in professional programs." But 84 percent agree that the concept of a liberal arts education is not well understood in the United States, and 61 percent believe that presidents, boards and politicians are "unsympathetic to liberal arts education." A majority reported that they feel "pressure" from presidents, boards and donors to focus on academic programs with a clear orientation toward careers.

While only some liberal arts education is provided at liberal arts colleges, those institutions are seen as crucial by many. A majority of provosts (54 percent) expect to see "a significant decline" in the number of liberal arts colleges over the next five years.

Mixed Views on Tenure and the Future of the Faculty

In an era in which many colleges are replacing tenure-track lines with adjunct positions, many faculty members hope that provosts will defend the institution of tenure. The survey results show general support for tenure, but openness to other approaches to faculty job security, and little expectation that the current reliance on adjunct labor will end.

In an era in which many colleges are replacing tenure-track lines with adjunct positions, many faculty members hope that provosts will defend the institution of tenure. The survey results show general support for tenure, but openness to other approaches to faculty job security, and little expectation that the current reliance on adjunct labor will end.

Nearly three-quarters of provosts agree or strongly agree that tenure "remains important and viable at my institution."

And more than three-quarters of CAOs say their institutions rely on adjunct faculty members. Will that change? More than two-thirds (67 percent) believe that their institutions will remain as reliant on adjuncts in the future as they are today. Only 8 percent anticipate becoming less reliant, and 25 percent expect to become more reliant.

In a sign that commitment to tenure is not absolute, 60 percent of provosts said that they would favor a system of long-term contracts over the existing tenure system.

To some who worry about the state of the academic job market, Ph.D. production is an issue. These observers say that if universities continue to produce Ph.D.s in fields without tenure-track positions available, use of adjuncts will only rise. Provosts are divided on this issue, but a narrow majority (52 percent) agree or strongly agree that graduate programs are "admitting more Ph.D. students than they should."

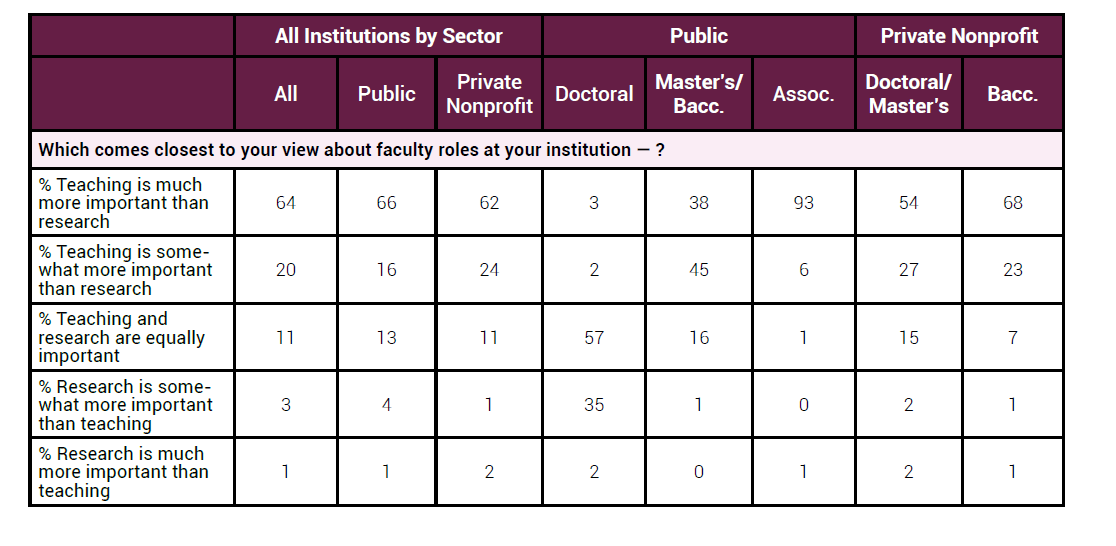

Teaching Versus Research

Many academic leaders state repeatedly that they value teaching as much as they do research. Many professors are skeptical and believe that research comes first, even at institutions that are teaching oriented.

The results of this year's survey show strong support for the teaching role, even at research universities.

Professional Development for Faculty Members

This year's survey asked provosts to indicate whether they offer professional development for faculty members on various topics. Overwhelming majorities of provosts indicated that they do:

- 94 percent on teaching with technology

- 94 percent on promoting student success

- 93 percent on promoting active teaching techniques

- 87 percent on using assessment systems

- 60 percent on evaluating the effectiveness of digital tools

Notably, most provosts who reported that their institutions did not offer professional development in various areas said that they would like to offer it.

One caution on these findings: when Inside Higher Ed surveys have asked both faculty members and administrators about the availability of professional development, administrators tend to say programs exist at much higher rates than do faculty members.

Paying for Textbooks

Increasingly in recent years, colleges have debated whether textbooks are too expensive (many agree) and what to do about it (there is far less consensus).

One issue that angers many students is when professors assign books that they have written, and on which they will earn royalties. Fifty-seven percent of provosts agree that this shouldn't happen. But two-thirds of provosts reported that their colleges permit such arrangements.

One issue that angers many students is when professors assign books that they have written, and on which they will earn royalties. Fifty-seven percent of provosts agree that this shouldn't happen. But two-thirds of provosts reported that their colleges permit such arrangements.

Most faculty members, of course, don't write commercial textbooks. But there has been a growing push by many students and some administrators for faculty members to factor in student costs when making choices about educational materials.

In a survey by Inside Higher Ed in October, faculty members overwhelmingly (93 percent) said they believed that course materials were too expensive, that instructors should make price a "significant concern" when assigning course readings (82 percent) and that professors should assign more free open educational resources (90 percent).

Provosts appear to share those views with considerably less enthusiasm (although it should be noted that the questions were not phrased identically).

Only 35 percent said that faculty members and institutions should be open to changing choices on materials to save students money, even if the lower-cost options are of lesser quality. The figure was highest in community colleges, where 43 percent of provosts answered that way. At many community colleges, textbook and educational materials make up a larger share of total education costs than is the case at four-year institutions.

When it comes to general education courses, 48 percent of provosts agreed that open education resources are of sufficiently high quality for use there.

In what could be a crucial issue in the years ahead, provosts seem hesitant to take away faculty control on textbook and educational material selection. Asked if the need to help students save money justified some lessening of faculty control over choosing educational materials, 38 percent of provosts agreed, while 41 percent disagreed.

Competency-Based Education

This year's survey reflects increasing support for competency-based education, in which students earn credit not based on class time, but on demonstrating an ability or set of skills related to various subjects. Just a few years ago, many provosts -- especially in private higher education -- were skeptical of the concept.

While public college provosts in this year's survey were more likely than their private counterparts (86 percent to 61 percent) to favor the awarding of credit based on competency, support is high across sectors.

Historically, skeptics of competency-based education have feared its impact on general education, but that worry appears to be evaporating. Only 26 percent of provosts at public institutions have this fear, while the figure is higher (47 percent) at private institutions.