You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

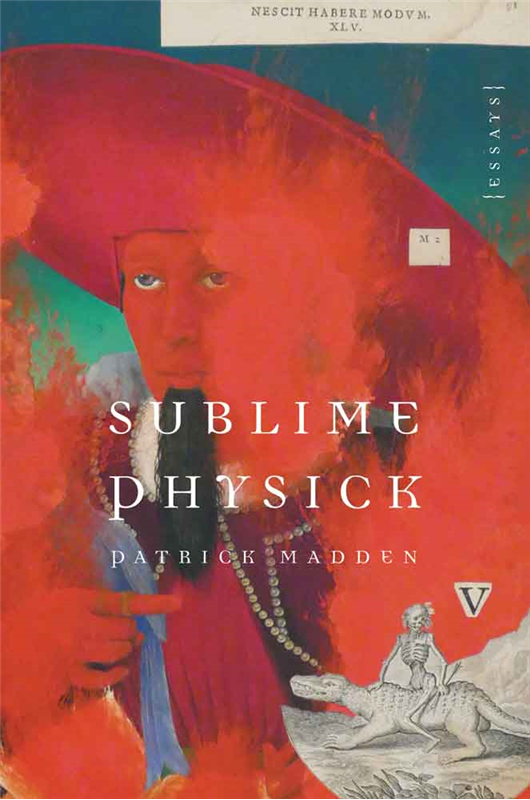

Sublime Physick: Essays. Patrick Madden. University of Nebraska Press. February 2016. $24.95 (hardcover).

Review by Renée E. D’Aoust

In the newly-released Sublime Physick, Patrick Madden has written 12 associative, discursive, elegant essays in the mode of Montaigne. Like the classical essayist’s varied, but basic, topics, no subject is too mundane for Madden’s contemporary pen. The collection asks in essence what it means to be human and how we might explore the idea of wonder.

Madden is not explaining himself to the world so much as he is writing towards an understanding of the world and his place in it. Frequently, favorite writers show the way. In “Empathy,” Madden discusses one of his heroes, Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano:

I read [Galeano’s The Book of Embraces] every chance I got, and then I read his other books, all outward looking, all bravely poetical, all celebratory, reveling in the complexities of our fellows, all written in unassuming prose that makes me forget I’m reading, so I can almost believe in a direct transfer of thinkingfeeling.

While reading Sublime Physick, I too engage in a “transfer of thinkingfeeling.” The idea of “thinkingfeeling” perhaps helps to explain the way mere words in a book can help a reader think beyond the limited experience of daily reality, as Galeano’s words do for Madden, and Madden’s words do for me:

This is what concerns me: that the vast part of life is absorbed into the unremembered whole; that so much is routine and forgotten; and that, going forward into what time we have left, so much of our life is a pointless spinning of wheels converting experience into sand through a glass or a sweeping hand around a clock face. And worse, we consent to live this way, only partially present, sleepwalking through life, as the poet says.

Madden brings Galeano to lecture at Brigham Young University, where Madden works. After the lecture, the two writers go hiking together. Their hike is recounted in Sublime Physick, but Madden first reads of it in Galeano’s Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone, which Madden quotes:

Stalactites hang from the ceiling. Stalagmites grow from the floor.

All are fragile crystals, born from the sweat of rocks in the depths of caves etched into the mountains by water and time.

Stalactites and stalagmites spend thousands of years reaching down or reaching up, drop by drop, searching for each other in the darkness.

It takes some of them a million years to touch.

They are in no hurry.

When Madden was in the Utah cave, he pictured animals in the rocks. Galeano saw none, though he wishes he, like the other members of the cave tour, might have seen the camel and elephant and flamingo shapes. Instead, Galeano describes the reality of crystal formations, of stalactites and stalagmites. “Of course,” Madden writes in response, at the end of his own essay; Madden realizes Galeano sees what is actually there. Rocks might take the shapes of imagination, but they are rocks first. Madden includes a photograph of Galeano in the cave, his eyeglasses hanging from a lanyard, his eyes bright as a bat’s.

When Madden was in the Utah cave, he pictured animals in the rocks. Galeano saw none, though he wishes he, like the other members of the cave tour, might have seen the camel and elephant and flamingo shapes. Instead, Galeano describes the reality of crystal formations, of stalactites and stalagmites. “Of course,” Madden writes in response, at the end of his own essay; Madden realizes Galeano sees what is actually there. Rocks might take the shapes of imagination, but they are rocks first. Madden includes a photograph of Galeano in the cave, his eyeglasses hanging from a lanyard, his eyes bright as a bat’s.

Madden uses references throughout to other writers, including songwriters, as a means to frame his thoughts. Madden quotes from his favorite band, Rush, in the opening essay “Spit”:

"Catch the witness, catch the wit.

Catch the spirit, catch the spit."Nobody I know has any clue about what this “means,” so I, having learned restraint in interpreting, attribute it to linguistic punning, the kind of composition that’s driven by shapes and sounds before significances. As with so much poetry, there’s the rhyme with wit, which is a paring from witness, but I also sense a smidgen of glee in the compression of spirit to spit, which reaches beyond sense to discomfort with the notion of sense. “What does this mean?” seems the wrong question to ask. No question would be appropriate.

No question is inappropriate in Sublime Physick. They abound in the text, serving as foils and sounding boards.

Madden also uses quotations to frame his thoughts, as in this passage from Dante to Montaigne:

One begins with the notion to write an essay from the middle of life, per Dante, per the Psalmist, with a yen for the exotic or the archaic lent by Latin, with a vague idea—the idea a curious Catholic would arrive at after listening to hymns and remnants in the Mass (supplemented by two years’ study of Russian in college)—of Latin’s grammatical declensions, a knowledge that life is vita and middle is media. From here it is only a few finger strokes to the originless Middle Ages saying, survived in hymns and a Mass, “media vita in morte sumus”:

In the midst of life, we are amidst death

Or as Montaigne frames it,

Death mingles and fuses with our life throughout.

--“Of Experience”This, though it was not originally part of my unwritten essay as it germinated in my mind, is my theme.

Death, then, is Madden’s ultimate theme, and he makes, eg, the leap from wearing a seatbelt to marriage to the deterioration of the body:

I always wear a seatbelt, I exercise and play sports regularly, I eat fairly well, and I’m married, which can keep you alive longer, I assume, not only because you have companionship and a reason to live but because you have someone to find you soon after your heart attack or stroke.

When Madden writes that essays “perform a kind of sublimation of the solid; from the concrete, they attain abstraction,” he’s alluding to the classical essay form, yet Madden’s work is current, of our time. In “Independent Redundancy,” Madden returns to death, to Montaigne, and to all essayists:

Thus I return again and again to death, Montaigne’s own obsession, spark of all religion, great equalizer of all living. There’s love, too, and fortune (my own good, others’ bad, my fears of chance’s icy interference in my contentment) and contentment, the tranquility of living well, the inescapability of systems (of humanity, of science, of language, of self), the implications of scientific understanding, the importance of art, epistemology, metaphysics, free will, the frustrations of busyness and joys of idle unfettered thinking, individuality and community, the interrelatedness of all people, the pompous self delusion of individual autarky and first-world entitlement, service to others, judgment and forgiveness, the essay as a way of apprehending the multifarious complexity of this marvelous world, the importance of attention, reverence. But these are the concerns of essayists in all places and times.

The essays in Sublime Physick are more than self-reflective; they connect internal states with the marvelous world.

***

Renée E. D’Aoust’s first book of essays, Body of a Dancer (Etruscan Press), was a Foreword Reviews "Book of the Year" finalist. Follow her @idahobuzzy and see www.reneedaoust.com.