You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

California State University, East Bay

Trial and Error is a recurring feature from “Inside Digital Learning” that examines the successes and struggles of technology initiatives on campuses and in classrooms. Have ideas for future columns? Send them to mark.lieberman@insidehighered.com. And be sure to comment below the story with thoughts and ideas for this institution.

The Institution: California State University, East Bay

The Problem: The university decided to switch from quarters to a semester schedule in 2014, which meant redesigning curricula for all courses -- face-to-face, online and hybrid. But no protocol for such a massive transformation process existed. Charged with a daunting task, the university’s Office of the Online Campus stepped up, as documented in a new report from the institution's instructional design team.

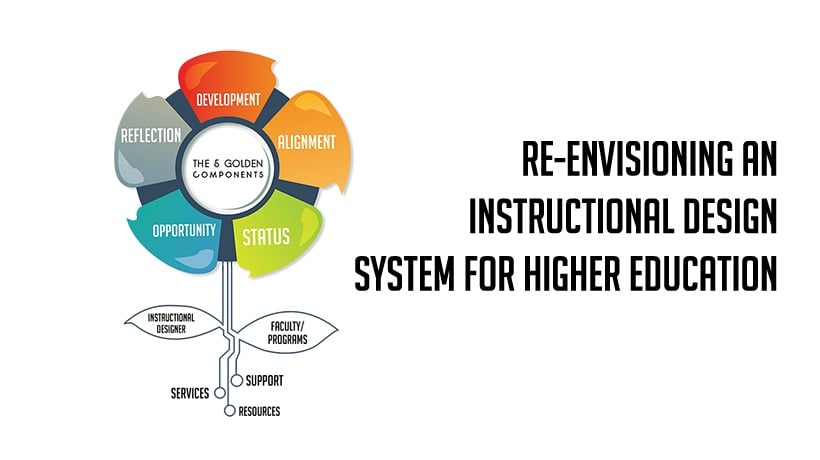

“The process of developing and finalizing such a system is an organic process that might be considered as an evolving life cycle,” the report reads. “All of the components are occurring simultaneously, similar to how a flower does not grow one petal at a time but blossoms all at once.”

The Goal: Molding classes to the new schedule was the top priority, but the instructional design team also wanted to take advantage of a massive opportunity to formalize and refine course design practices. The possibilities of that project emerged gradually, according to Cheryl Saelee, an elearning specialist in the online campus office.

“We just kind of started identifying these different components as we’re discussing with faculty,” Saelee said. “It came from anecdotal information from each of us, the similarities that we were all having.”

The Experiment: The team eventually settled on a system they liken to a “plumeria flower, where the flower petals blossoming represents the life cycle of the course development over time.” The five-leaf flower represents components of the design experience:

Status. The online instructional design process begins with a project request from an instructor. At that point, the design team schedules a series of meetings with faculty or program chairs to review course inventory, reveal subject matter restrictions and -- most importantly -- share progress. This setup allows members of the team to identify areas that could be improved as early as possible.

Opportunity. Faculty members can point throughout the process to areas of their courses that need improvement. Designers keep instructors posted on ideas, program requirements and possible tools and pedagogy that could improve their course. “This simultaneous exchange of ideas between faculty and the online instructional designers in assessing the teaching and learning experience is the central point for this opportunity component,” the report reads.

Alignment. In addition to traditional factors like course and unit-level objectives, instructional designers at the institution consider program-level requirements, accreditation alignments, funding parameters and technical standard operating procedures. According to the team, this step most significantly distinguishes this instructional design approach from others, which tend to concentrate more on addressing a faculty member’s course, or even an activity within a course.

Alignment. In addition to traditional factors like course and unit-level objectives, instructional designers at the institution consider program-level requirements, accreditation alignments, funding parameters and technical standard operating procedures. According to the team, this step most significantly distinguishes this instructional design approach from others, which tend to concentrate more on addressing a faculty member’s course, or even an activity within a course.

When Saelee teamed up with the institution's paralegal program, she realized the importance of understanding the demands of the discipline before trying to improve it.

“It wasn’t until our third or fourth meeting [with the program director] that he said, ‘Oh, wait, we need to make sure that we’re also following [American Bar Association] standards,’” Saelee said. “I was like, ‘OK, this probably should have been done from the beginning.’”

Development. Instructional designers are required to “frequently re-train themselves” as they take on complex projects involving adaptive learning, artificial intelligence and high-impact practices. This “leaf,” according to the report, is the one most commonly included in other universities’ instructional design responsibilities.

Reflection. Quality-assurance rubrics come into play here, as designers must constantly interrogate their assumptions and engage in self-evaluation.

Instructional designers now go through a six-week process for basic training that includes the learning management system and adaptive learning tools. The team has applied the model to more than 70 courses, according to Roger Wen, senior director of the online campus.

What Worked (and Why): Saelee said she’s worked at other institutions where a tug-of-war between faculty interests (pedagogy, student success) and business interests (accreditation, efficiency) leaves instructional designers as beleaguered mediators. Cal State East Bay’s approach, by contrast, lets instructional designers “support both sides and see where a lot of these priorities match. A good, happy student is good for business,” Saelee said.

The five-pronged approach is particularly well suited to an institution like Cal State East Bay, according to Monica Munoz, curriculum support specialist, because of its position within the bureaucratic network of a 23-institution system that imposes its strategy above and beyond member institutions' priorities. Each step ensures that instructional designers look holistically at the academic ecosystem, rather than focusing only on one course at a time.

The extra sessions afforded by the new semester schedule allowed designers to make their mark with instructors who hadn’t taught in hybrid or online formats. For instance, Munoz suggested one instructor incorporate more guest lectures, offering students a broader range of perspectives and more variety.

What Didn’t (and Why): As faculty members started having success with the instructional design method, the instructional design team started getting inundated with an influx of requests.

“Our IDs are doing a wonderful job,” Wen said. “Almost because they’re so good, our requests increase, their loads increase.”

Explaining the complexities of the team’s process was difficult at times because each of the five components overlaps with others, Munoz said.

“We all know what we do every day,” Munoz said. “Trying to identify those pieces, break them down in a way someone else would look at and understand, I think that that was a little bit challenging.”

Munoz sometimes struggled to look at an existing online class and determine how many hours of work it actually required -- a step that was necessary before converting the course to a different time span.

What’s Next: OER initiatives are high on the priority list. The team also just hired its fourth instructional designer and hopes to grow a bit larger.

“We just very recently shared our system with her,” Saelee said. “I’m actually really interested to know how she kind of interprets our system and introduces it into her process and development as an ID.”

The five-leaf model will be the foundation for those efforts.

"When it comes to actually implementing the process, that part is very organic. It almost comes natural to each one of us when we’re sitting down to meet faculty," Munoz said. "There’s definitely no linear process. It’s not one-two-three, trying to hit points. It’s more about how we use that love and care to support faculty and bring courses to students."