You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Keith Bell/123rf.com

The broad public policy push for more Americans to get a higher education leans heavily on the idea that those without a college degree are up a creek, because so many jobs in today’s technology and information economy (and more in tomorrow’s) will require a credential. Many critics of higher education, in turn, complain that the "college completion" movement has been fed by (and feeds) credential inflation, with employers imposing a degree requirement for many jobs that never required one (and still don’t) simply because they can.

A new report offers evidence to support both arguments -- and reasons both for college officials to be optimistic about continuing demand for their degrees and to see danger signs on the horizon.

The report, "Moving the Goalposts: How Demand for a Bachelor's Degree Is Reshaping the Workforce," is from Burning Glass Technologies, a Boston-based firm that studies employment markets by analyzing job advertisements.

By comparing the educational attainment that employers are seeking in new workers (as evidenced in their job advertisements) with the current profile of the workforces in various fields, the study aims to quantify the extent of "upcredentialing" -- the phenomenon in which employers are seeking workers with degrees or credentials for jobs that have not historically required them. The focus is on "middle skills" jobs -- the many categories in the middle between entry level positions and high-skilled and upper-level managerial positions.

The phenomenon has been much debated among some economists. Those who support the Obama administration's push for more Americans to get postsecondary education and training argue that credentials bolster workers' employment prospects and that the country will need more workers with degree-certified skills in the future to be economically competitive. Others believe that by hiring more credentialed workers for jobs that don't require them, employers are squeezing out non-degreed workers and driving more people to pursue degrees, supporting a not-very-efficient higher education system.

"[T]he problem is not that employers are demanding more education, but rather that educators and public policy makers are producing more degrees, giving employers a large pool of applicants, and demands for the higher credential (e.g., bachelor’s degree) are instituted to narrow the applicant pool to a manageable size," Richard Vedder and the staff of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity wrote several years ago. "Other things equal, on average, college graduates are somewhat smarter, more disciplined, and perform better academically than non-graduates. The probability that a prospective employee will be successful vocationally is traditionally enhanced by obtaining a degree -- independent of whether the individual 'learned' much while in college. This is a classic example of what the French economist Jean Baptiste Say said over two centuries ago: supply creates its own demand (Say’s Law)."

First and foremost, the Burning Glass analysis confirms that upcredentialing is real and widespread.

In many fields and for many positions -- insurance claims clerks, executive secretaries, many human resources roles, and the people who supervise mechanics and installers -- employers are growing much more inclined to try to replace workers who do not have bachelor's degrees with employees who do.

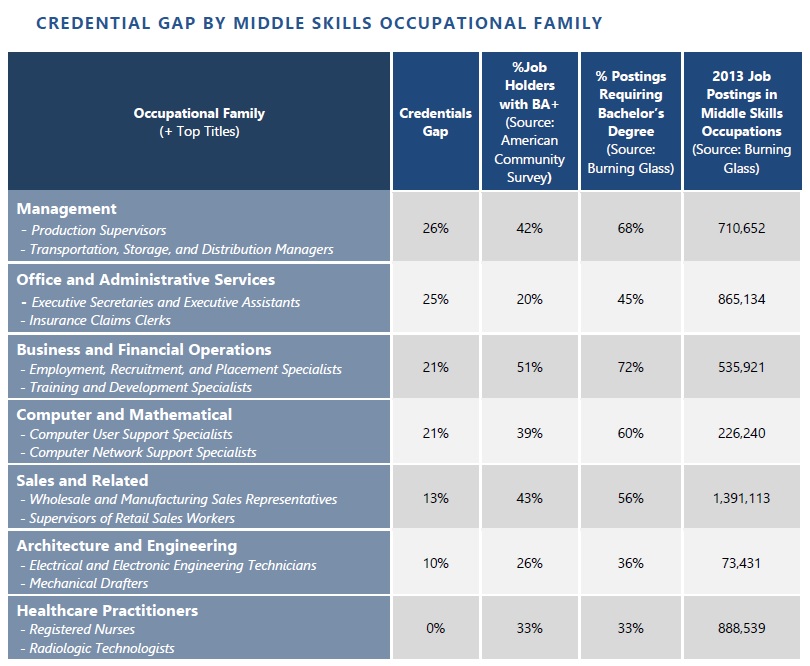

As seen in the table below, the gap between the proportion of current workers in a field who have B.A.s (drawn from U.S. Census Bureau data) versus the proportion of positions available in those fields in 2013 for which employers listed a four-year degree as a requirement was 25 percent or more in some broad fields, and significantly higher for some individual jobs.

The gaps were significantly higher for some specific jobs. A full 65 percent of the postings reviewed by Burning Glass for executive secretaries and assistants required a bachelor's degree, for instance, while just 19 percent of the current holders of those positions have four-year degrees, a 46 percentage point gap; the difference was 34 percentage points for supervisors of mechanics and installers and 25 points for training and development assistants in human resources departments.

Why is this happening? The explanation typically offered to explain the upcredentialing phenomenon is that the middle skills positions are becoming more technological and complex, and therefore require a greater level of education and training.

Burning Glass finds that that's true -- to an extent. The job requirements in advertisements for positions such as electrical and architectural drafters, for example, reflect the fact that the positions are becoming more like "junior engineers," due to computer-assisted design and other software. And job postings for loan officers that demand a bachelor's degree are more likely to ask for national accreditations and specific skills than do other postings for those positions, Burning Glass found.

But credentials gaps exist for other positions that are not evolving or growing more complex quickly, the study found. Postings for IT help-desk jobs are comparable whether they require a bachelor's degree or not -- but 60 percent of new postings for the jobs require a B.A. while only 39 percent of workers currently in those positions have a degree, for a 21 percentage point credentials gap. (There is little difference in the skills requirements in postings that require a bachelor's degree and not in other fields, too, such as many HR and clerical positions.)

"This strongly suggests that, in such occupations, employers have come to rely on a bachelor's degree primarily as a way of screening applicants, in a way that may not be related to job duties themselves," Burning Glass says in its report. That is true even though the four-year-degree requirement often makes the jobs harder to fill: "help desk jobs calling for a bachelor's degree take 35 percent longer to fill on average than those that do not," the report adds.

Interestingly, Burning Glass finds that some fields are not seeing credentials creep. As seen in the chart above, most health care fields (except for nursing) are not demanding more degreed workers. Burning Glass's explanation? "What these positions have in common are strong credential requirements that exist outside the traditional higher education degree structure: state licensing requirements, certifications accepted industrywide, or specific measurable skills," the report states. "Employers have specific criteria to use as a yardstick when hiring, so there's not as much incentive to apply the less-specific screen of a bachelor's degree."

Implications

Economists who are concerned that too many people are going to college -- like the aforementioned Richard Vedder -- are likely to find much to like in this report, given that it proves that employers are demanding degrees for jobs that haven't historically required them.

But Anthony Carnevale of Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce, who is among the economists who are generally pro-credentials, also applauds Burning Glass for producing "good data" and generally agrees with its analysis. For him, though, the most important point gets comparatively short shrift in the Burning Glass report itself, even though its data are clear: the employers are paying higher salaries to the college degree recipients they are hiring than they are to the non-degreed workers.

"It's the old economists' rule: If somebody's putting the money down, then they're willing to pay that person more than the person you thought was just O.K. for the job," he said.

Why would they pay the higher wage if there isn't a shortage of candidates? "The reason is, they're looking for something and hoping that the degree will signify that. It may be a deeper skill set that doesn't show up in the other requirements, the ability to work in teams, all that stuff. Employers are wanting that in more and more jobs, and they're clearly willing to pay the wage [to those with degrees] because they think they will get that."

He adds: "If you're paying the wage, you're trying to buy something."

Matt Sigelman, chief executive officer of Burning Glass, agrees that the report provides evidence both that the degree requirement "is a filter that employers are using that causes some inefficiency" and that it "represents a perception of the value of the college degree."

"In the absence of other reliable mechanisms that people bring with them, employers will gravitate toward the college degree as a proxy for someone's work readiness," Sigelman said.

In that way, the Burning Glass report is good news for those in higher education right now. "This does show the appetite that employers have for the college degree, and likely for the additional value that B.A.-holders have in the marketplace," Sigelman said.

And for the "pretty significant portion of jobs" Burning Glass examined for which the job requirements are getting more complex and sophisticated, that degree premium is likely to hold.

But there is some peril for colleges and universities in the example of "corners of the market that have been most resistant to upward credentialing," Sigelman said. Those are typically fields where there are "good alternatives, either direct or indirect," to the degree as a proxy -- licensing exams, national certifications, or just clear skill requirements that can be readily measured or captured.

Significant work is being done within and outside higher education to try to develop sub-baccalaureate credentials or improve methods of measuring competencies or mastery of skills and knowledge, and if alternative (and shorter-term) credentials of some sort develop in more areas, "that could take some of the pressure off the higher education system as the sole pathway" to middle-skills jobs, Sigelman said.

"Looking down the road, there has to be some way to address the employers who don't necessarily think the college degree is really valuable, but just have no alternative for validating that people are work-ready," he said. "Four-year schools need to be really careful that they are providing some job market preparedness, beyond just the credential."