You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Beth Akers and other experts at a 2015 Senate hearing on student debt

U.S. Senate

Roughly two-thirds of undergraduates are paying more for college than is recommended by a common benchmark for affordability.

That's the top-line finding of a new report by higher education experts from three think tanks with a range of political perspectives, the American Enterprise Institute, the Manhattan Institute and New America.

The report attempts to answer the question of for whom is college affordable, and why?

Its authors used a federal data set from 2012 that includes the tuition rates and fees, room, board and other expenses that full-time students nationwide spent to attend college. The researchers then compared that data to an affordability measure, dubbed the Rule of 10, that Lumina Foundation created in 2015.

That benchmark says students and families should pay no more for college than the savings they can accumulate by setting aside 10 percent of their discretionary income (earnings above 200 percent of federal poverty guidelines) for 10 years and with the additional income students earn from working 10 hours per week while enrolled, which would be roughly $14,500 for four years of work at minimum wage.

For example, a single working adult student with no children should expect to pay $6,460 in total for a degree, under the benchmark. But an upper-income family of four might be able to contribute $51,500, with any college students in the family chipping in another $3,625 per year.

The findings suggest that 68 percent of undergraduates overpaid, on average ponying up twice the recommended amount.

Student loans are not included in the price-based Rule of 10, because the benchmark represents what students and families should expect to pay out of pocket. Not surprisingly, the report found that substantial student loans are used to cover the net price of a college degree -- which averaged $54,092 across the data set. (Net price is the amount students actually pay, having subtracted non-loan financial aid.)

On average, students and families will take on $16,498 in debt to pay for 30 percent of the cost of credentials (both associate and bachelor's degrees), the study found. Students earn a similar amount, $16,248, while in college.

That means the remaining 40 percent, or $21,346, comes from somewhere else, such as savings, parents' earnings, other forms of credit and unreported support from friends or family.

"Combining student earnings and borrowing did not tend to cover the net cost of enrollment. Even after families contributed an amount equal to the level of savings recommended by the Rule of 10, the average shortfall was $2,510," the report found. "Students and their families are necessarily finding a way to finance this additional sum, probably by devoting more savings than is prescribed by the benchmark, or perhaps through using other forms of credit such as home equity or credit cards."

The report goes beyond aggregate numbers, however, in an effort to bring some nuance to discussions about college debt. It finds wide variation in expenses and borrowing when the data are broken out by family and student income levels as well as factoring in which type of institution a student attended.

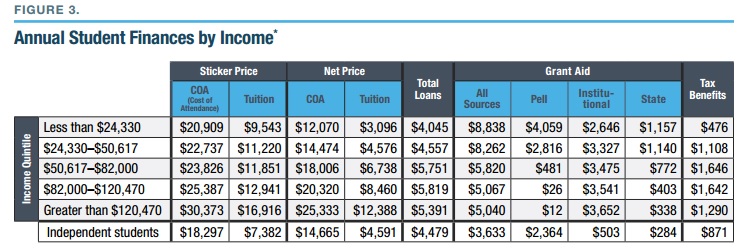

For example, the wealthiest students typically pay the most to attend college. Dependent students from the highest income quartile spent an average of $92,341 for their degrees compared to the $38,841 paid by students from lowest quartile. That's often because wealthier students choose to attend more expensive colleges, the report said. (See chart, below.)

Income also heavily influences borrowing, but perhaps not in the way some would expect.

While the share of students with college expenses above the affordability benchmark declines as family income increases, the report found that the highest levels of student debt are taken on by students whose parents are in the second-highest income quintile (household earnings of $82,000 to $120,470).

These students, who could be classified as solidly upper-middle class, borrowed an average of $5,819 per academic year. That's 44 percent more than the lowest-income students, who borrowed an average of $4,045.

Since relatively well-off families tend to have options for paying for college other than debt, the report's authors write that many cases of high-level borrowing may be driven by choice rather than necessity.

"People may be choosing to spend more on college than they really have to," said Elizabeth Akers, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and one of the report's co-authors. And since a college degree can be viewed as an investment, she adds that the choice to spend more is "not necessarily a bad thing."

Defining Debt

The report includes caveats about reading too much into using the Rule of 10 in assessing college affordability.

For example, the benchmark doesn't measure value or return on investment.

"The problem is that benchmarking affordability based on price alone is akin to a one-sided financial balance sheet -- one that displays only a company’s liabilities and ignores its assets," the report said. "In this case, the liability is the price for the education, and the asset is the education and the future earnings that a student will gain from it."

A more telling measure, the report said, would look at college affordability with a value-based measure that factors in a degree's impact on long-run financial returns from more consistent employment and higher earnings.

In addition to benchmarking the up-front expenses of attending college, Akers said the new report is an attempt to clear away some of the confusion about the enormously complex issue of student debt.

More students are taking on loans. In 2000, the typical student covered 38 percent of their tuition and fees with debt, compared to 50 percent in 2013, the report said. But not everyone agrees on how to look at debt, let alone how to deal with the problem.

For example, two years ago Akers talked about student debt at a hearing of the U.S. Senate's education committee. Senator Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat, took issue with Akers's testimony that the debt most students accrue is offset by graduates' higher earnings.

"It just seems to me, based on your research and on the Fed's research -- both of which show a substantial increase in debt loads -- that it is a serious problem," Warren said. "And I don't think it's responsible to sit here and claim that borrowers are, quote, 'no worse off' while people are still struggling to make much higher student loan payments than ever before and carrying their debt for much longer than ever before."

Warren's take was based on a human capital model of paying for college, Akers said, while Akers, an economist, had been focused on the liquidity issue.

"There are actually a lot of different definitions of affordability that are floating around the policy space," she said.

In the report, Akers and her co-authors try to set a clearer baseline for the up-front price of college. But they argue that a value-based framework is needed to truly measure affordability.

"Otherwise, financially advantageous educational opportunities will be passed over for opportunities with a smaller price tag, even when the prospects are worse," the report concludes.

(Note: This article has been changed from an earlier version to include an updated figure from the researchers about the overall percentage of undergraduates who pay too much for college under the benchmark.)