You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

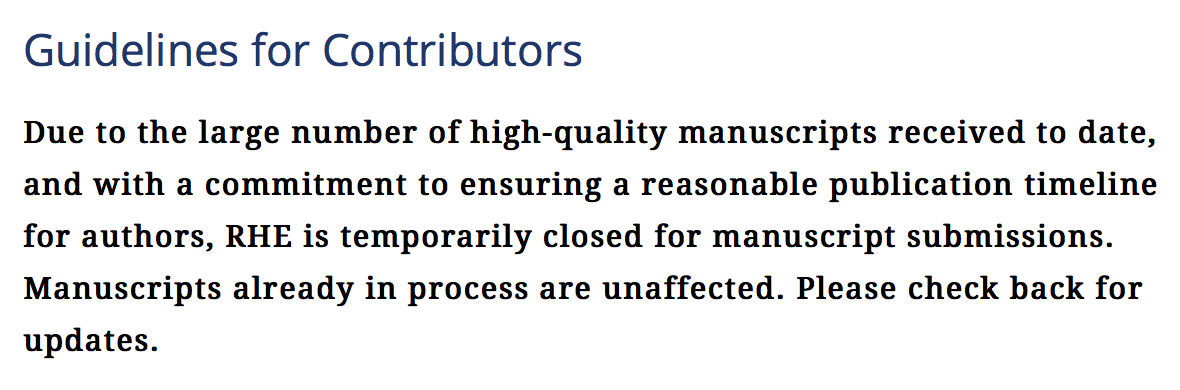

Those looking to submit an article to Review of Higher Education this summer probably saw this message on the journal’s website:

The missive has proven jarring, given that Review is one of the field's most prestigious publications and the official journal for the Association for the Study of Higher Education. It’s also led to interesting discussions among scholars about what it means when a top journal is too swamped to take on more papers -- and is wiling to admit it.

“We’re victims of our own success, a little bit,” said Gary Pike, a professor of educational leadership and policy studies at Indiana University at Bloomington and editor of Review. “We’ve had a significant increase in the last four years in numbers of submissions, and an increase in the quality of submissions. What’s happened is we’ve developed a substantial backlog of accepted articles.”

A two-year backlog, to be exact. And telling scholars soon going up for tenure that their articles would be published in 2020 wasn’t a big help to them, Pike said. So the tentative plan -- which ASHE must still approve -- is to suspend submissions through early 2019, and begin to publish 10 articles per quarterly issue instead of the current five.

Once the initial backlog is cleared, seven articles per issue might be a more sustainable count, Pike said, noting that every editor wants some reserve of articles (just not two years’ worth). Pike also said he’s talking to Johns Hopkins University Press, the journal’s publisher, about expanding the use of its online-first platform for accepted articles, to make them publicly available sooner.

Still, for the time being, a major journal coming off-line is big deal for higher education scholars.

“This is one of the top three to five journals in our field,” Kevin McClure, an assistant professor of higher education at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, said in an interview Wednesday. “And it’s the expectation at some bigger research universities that scholars will not just be publishing in one of these journals but all of them.”

Put another way, “People have struggled to get anything in these journals to begin with,” McClure said. “[Review] accepts less than 10 percent of submissions, so now something that was hard to do is impossible. That affects people’s ability to advance in their careers.”

McClure wasn’t condoning academe’s emphasis on publishing in a tiny share of elite journals, just describing it. And many other scholars have urged disciplines beyond education to value publication in a more diverse set of quality journals, especially with respect to tenure and promotion.

Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University who has blogged about Review, said in an interview that while members of one’s own department might recognize and reward publication in a broader set of journals, collegewide committees from different disciplines might not. So in his own tenure application, he said, he’s including information about the impact factors of journals that might not have instant name recognition outside his field.

“I think it’s up to people applying for tenure to teach and showcase that there are other journals that are selective and impactful.”

Pike said that Review now publishes 5 to 7 percent of submitted manuscripts. Asked if he agreed with McClure, Kelchen and others who say that there’s too much emphasis in academe on getting published in a small fraction of journals, Pike laughed and said, “Now you’re asking me to go against my own economic interests.”

Turning serious, Pike said he’s currently shopping papers on the impact of high school training in science, technology, engineering and math on college STEM performance with engineering journals. So “there is merit in counting publications from a diverse set of high-quality journals,” he said. “Of course I would like to see everyone have at least one publication in our journal.”

In discussions on social media, some have attributed Review’s backlog to a common problem in academic publishing: trouble finding reviewers. And many journal editors report that finding reviewers for papers is getting harder, given increasing submission rates, more demands on faculty members’ time at work and the fact that reviewing is not compensated beyond a karmic notion of “review and be reviewed.”

As McClure said, “It is weird that the entire academic publishing industry rests on this volunteer service, so of course complications are going to arise.”

Jenny Lee, professor of higher education at the University of Arizona and an associate editor at the journal, said on Twitter that more than 25 scholars “rejected/ignored my request to review a single manuscript. Each takes weeks and some never respond. Not a challenging piece just ‘busy.’”

Lee on Twitter also raised questions about the role of journals’ editorial boards, suggesting that members should be expected to do more, presumably reviewing. It’s not the first time that the role of editorial boards has been called into question. Last year, for example, half of the editorial board of Third World Quarterly resigned, asking why they hadn’t been asked to weigh in on a controversial piece on colonialism.

Robert K. Toutkoushian, a professor of higher education at the University of Georgia and editor of another similarly named journal, Research in Higher Education, said that that publication has a consulting editorial board of 40 academics who have agreed to review between four and eight manuscripts per year, or about two-thirds of all reviews. Still, he said, he often has to go beyond the board to find reviewers with a particular expertise. And his success rate there isn’t too high.

“Often I never hear back from the person that I invited to review,” he said via email, noting it can take weeks or months to find someone with the right qualifications.

At the same time, Toutkoushian added, “there are individuals in our field who go above and beyond the call of duty to review manuscripts. I am amazed -- and deeply appreciative -- of the efforts that they make to not only conduct reviews, but provide thoughtful and constructive feedback to authors.”

Lee didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment, but Pike said the tweet about finding reviewers was in reference to a very particular manuscript: his own. Despite the fact that papers go out for review stripped of authors’ names, Pike said he suspected the some potential reviewers were otherwise able to identify the paper as his and therefore sought to avoid reviewing an editor.

In Pike’s own experience, a very bad day recruiting reviewers means approaching nine and getting two to say yes. But Review doesn’t typically have such a hard time finding reviewers, and the current crisis is about placement in the journal, he said.

For reference, four years ago the journals received 250 to 275 manuscripts over the course of a year. This year, the journal was projecting about 350 submissions. Toutkoushian said his journal received 672 submissions last year and published about 40 articles.

Similar increases in other fields have been attributed, in part, to increasing pressure for graduate students to publish. J. David Velleman, professor of philosophy at New York University, even suggested last year that graduate students should not be published, to free up the review and publication pipeline. Velleman also alleged that the quality of publications was declining as a result of the overall pressure to publish.

But that is not what Pike says is happening at Review, where submission quality remains high. The journal doesn’t get too many single-authored papers from graduate students, anyway, he said. Still, Kelchen said that when he was hired five years ago, he didn’t have any publications. Today, unpublished graduate students probably wouldn’t get an interview. That means faculty members have to step up and do the work of reviewing them where there is a dearth of reviewers, he added. (McClure also suggested that good reviewers be recognized by professional associations or invited to join editorial boards based on their reviewing records.)

Ultimately, though, Kelchen said, journals either have to become even more selective, in part by rejecting more papers before they even go out for review, or by publishing more articles.

Brendan Cantwell, associate professor of higher at Michigan State University and coordinating editor of Higher Education, an international journal, said Wednesday that it publishes two volumes and 12 issues per year. It got 1,100 submissions in 2017, but it has more space than some other publications. And its impact metrics are competitive with top journals in the field, Cantwell said.

In contrast to journals that believe exclusivity or "restricting access" signals "status or quality," he said, “Our approach is to publish a higher volume of good peer-reviewed work.”

Lori Patton Davis, professor of urban education at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis and president of ASHE, said via email that the Review backlog “actually reflects an increased volume of high-quality scholarship, coupled with the desire to have one’s work featured in the premier journal for higher education research. With high volume comes significant requests for more reviewers and a speedier review process.”

ASHE’s goal is to reopen the submission portal “as soon as possible, while also being responsible about addressing the backlog. We certainly value the work of scholars who view [Review] as the publication venue of choice,” she said.