You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Citation counts supposedly demonstrate a researcher’s scholarly impact. But outside factors can corrupt this metric. One of those factors is where a first author’s name falls in the alphabet, according to a new study. This is especially true in psychology, where convention dictates that in-text citations are ordered alphabetically.

When the study’s authors compared psychology journals to those in biology and geoscience -- both of which typically list authors chronologically in in-text citations -- the effects of alphabetizing in-text citations appeared to bias citation decisions toward authors with last names from early in the alphabet. So, say, a Professor Dumbledore would be cited frequently than, say, a Professor Snape, by virtue of a the first letters of their last names.

The study's authors attribute this finding to an interaction between cognitive biases -- specifically the primacy effect, which says that we more easily recall items earlier that appear earlier in a list -- and the citation environment, or style. The fix? Journals using alphabetically ordered citations should “switch to chronological ordering to minimize this arbitrary alphabetical citation bias,” the authors say.

Jeffrey Stevens, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, co-wrote “Order Matters: Alphabetizing In-Text Citations Biases Citation Rates” with Juan F. Duque, now an instructor in psychology at Arcadia University. The paper is in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. Stevens said last week that he was interested in this area of research because he was originally trained as a biologist, with a different citation approach.

Only later in his career did he get into psychology, he said, and transitioning to alphabetizing in-text citations “didn’t make much sense to me.” Stevens got to thinking about the consequences of such a system and the primacy effect, and realized “this could lead people to ignore articles listed later in the in-text citations.”

Stevens explained the phenomenon via email, saying that "biology might include the following citation (Darwin 1859, Anderson 2018), whereas psychology would use this (Anderson 2018, Darwin 1859). If there is a long list of papers in the citation, we will likely just read/focus on the first few." (Note: Stevens's example has been updated, at his request.) For biology, he said, "that means focusing on the early work, which is often the most important. For psychology, that means focusing on people with last names early in the alphabet, which is not necessarily the most important. We are also more likely to cite the papers that we focus on."

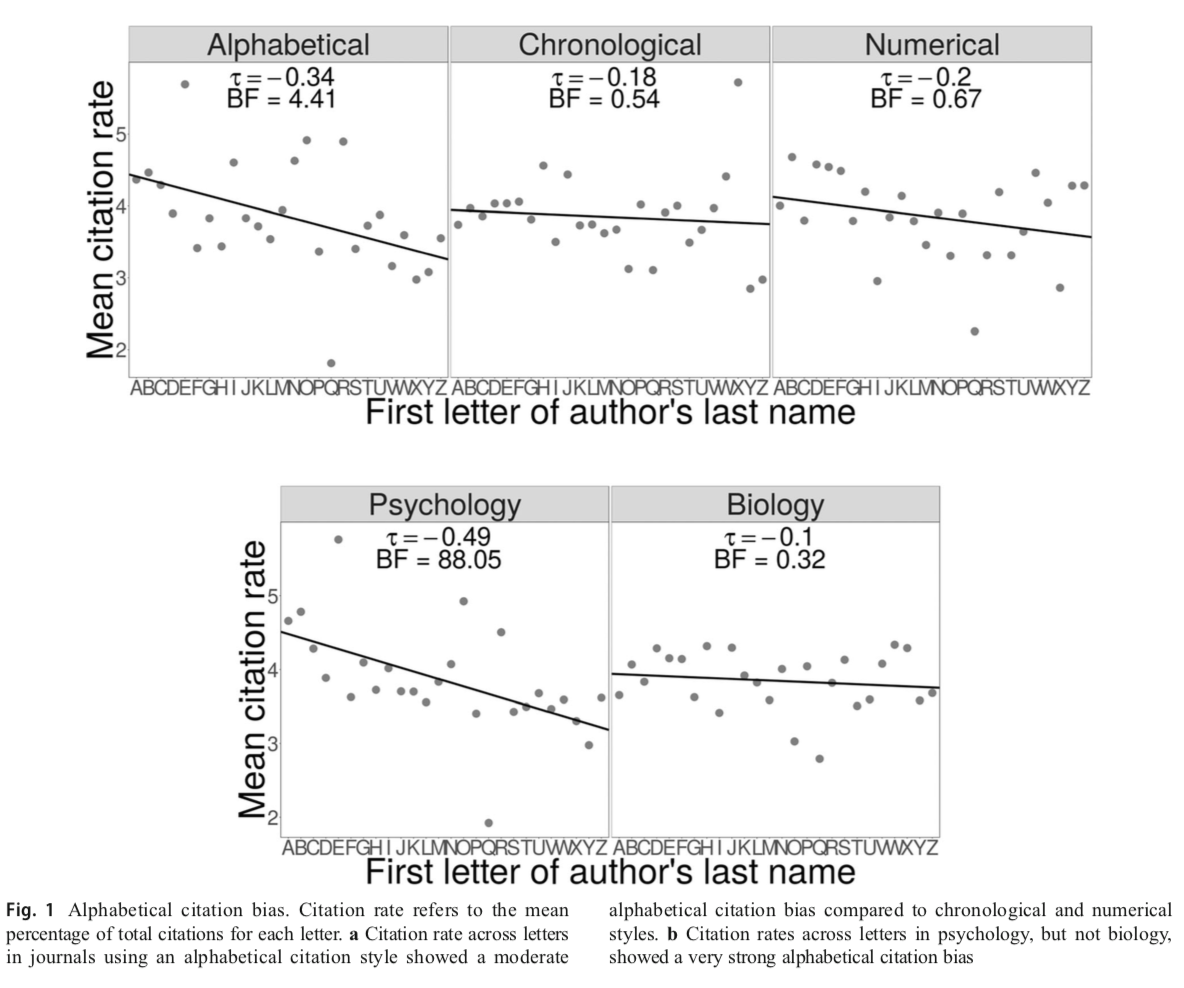

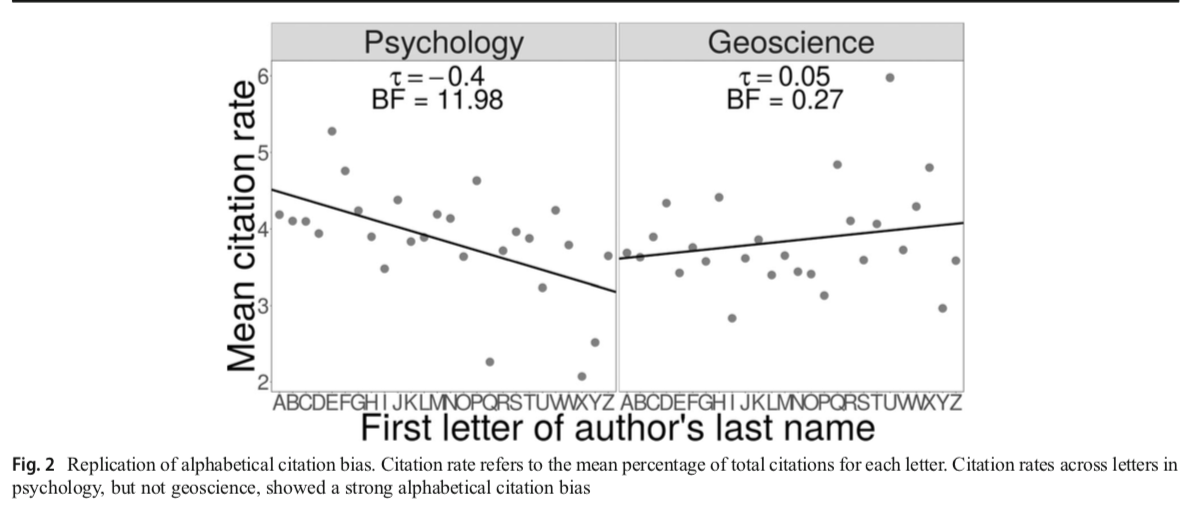

For their study, Stevens and Duque first looked at citation rates of tens of thousands of articles in 27 journals across psychology and biology. More precisely, they measured citation rates by looking at the number of times that each article was cited in Web of Science, and then calculated the average number of citations for each letter of the alphabet. Next, they divided that mean citation rate for each letter by the total number of citations, and multiplied that by 100 to get the average citation percentage for each letter. They next replicated their study, preregistering a very similar experiment involving psychology and geoscience journals.

As predicted, they found that in psychology, authors with last names early in the alphabet had more citations than those late in the alphabet. But that wasn't the case for biology and geoscience, which tend to order chronologically.

Categorizing the articles studied by field shows that the citation rate in psychology very strongly decreased with the letter of the first author's surname, the paper says, whereas biology showed no correlation. Comparing models without the field, and just by letter interaction, showed only weak support for any difference. But the replication involving geoscience journals also showed that alphabetical citation bias exists in psychology, and not where chronological lists exist.

Stevens said the findings matter because a seemingly arbitrary choice about ordering citations can influence citation rates, which have high-stakes implications for academics. And while psychology may be “relatively unique in forcing these arbitrary rules across the whole field,” he said, other disciplines, such as sociology and political science, at least allow that type of ordering.

“Though the effects might not be as strong, other fields could potentially have the same bias,” Stevens said.

Psychology’s citation rules are set by the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, which says that in-text citations must by alphabetized. (In-text citations include the author’s last name and year of publication.) Kim Mills, spokesperson for the organization, said via email that the “APA is constantly monitoring usage and feedback and we periodically make changes as we deem appropriate.”

Yves Gingras, a professor and Canada Research Chair in history and sociology of science at the University of Quebec at Montreal, who has written critically about how citation metrics are used to evaluate individual scholars, said that upon first read, the paper’s premise was interesting but that the effect size is relatively small and should be tested further. That said, he added that he had “no particular objection to the idea of making [citations] in chronological order from the older to the most recent or the reverse.”

It always always good to exercise caution when using citations for faculty evaluations, he said, and one way of doing that is looking at the way references are made.

Asked if his findings said anything bigger about the flawed nature of bibliometrics and the perils of relying on them too much for personnel decisions, Stevens said the question wasn’t necessarily relevant to his research.

“We used citation rates because they are easy to measure for our purposes,” he said. “The real issue is simply that authors early in the alphabet get more exposure or attention, and citation rates are just easy-to-measure proxies of attention.”