You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

It’s common advice: to increase faculty gender diversity, increase the gender diversity of institutional leaders. But what about department chairs, a kind of middle-management position -- do they make a difference? And beyond gender diversity, does having a female chair help improve the success of female academics?

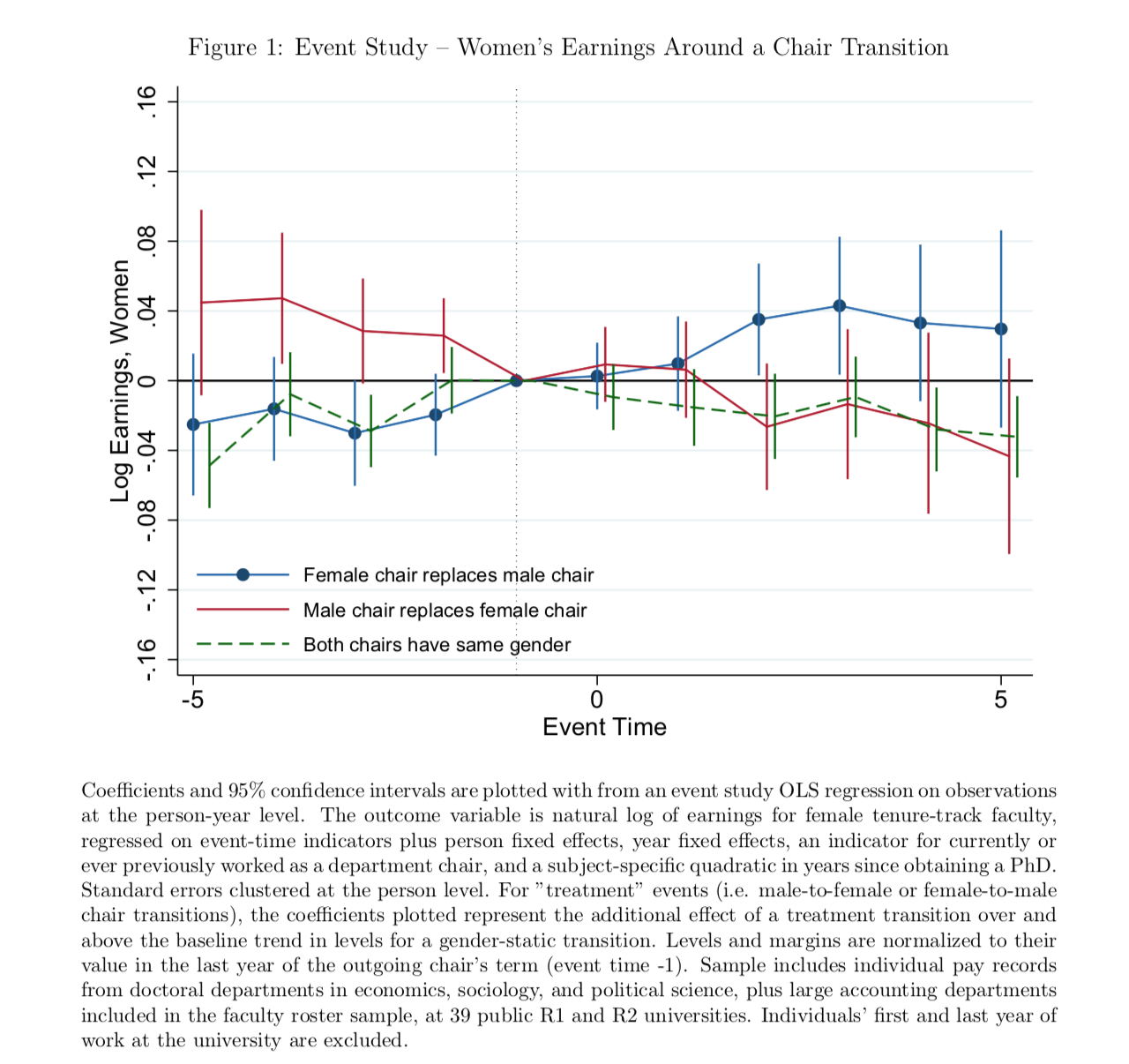

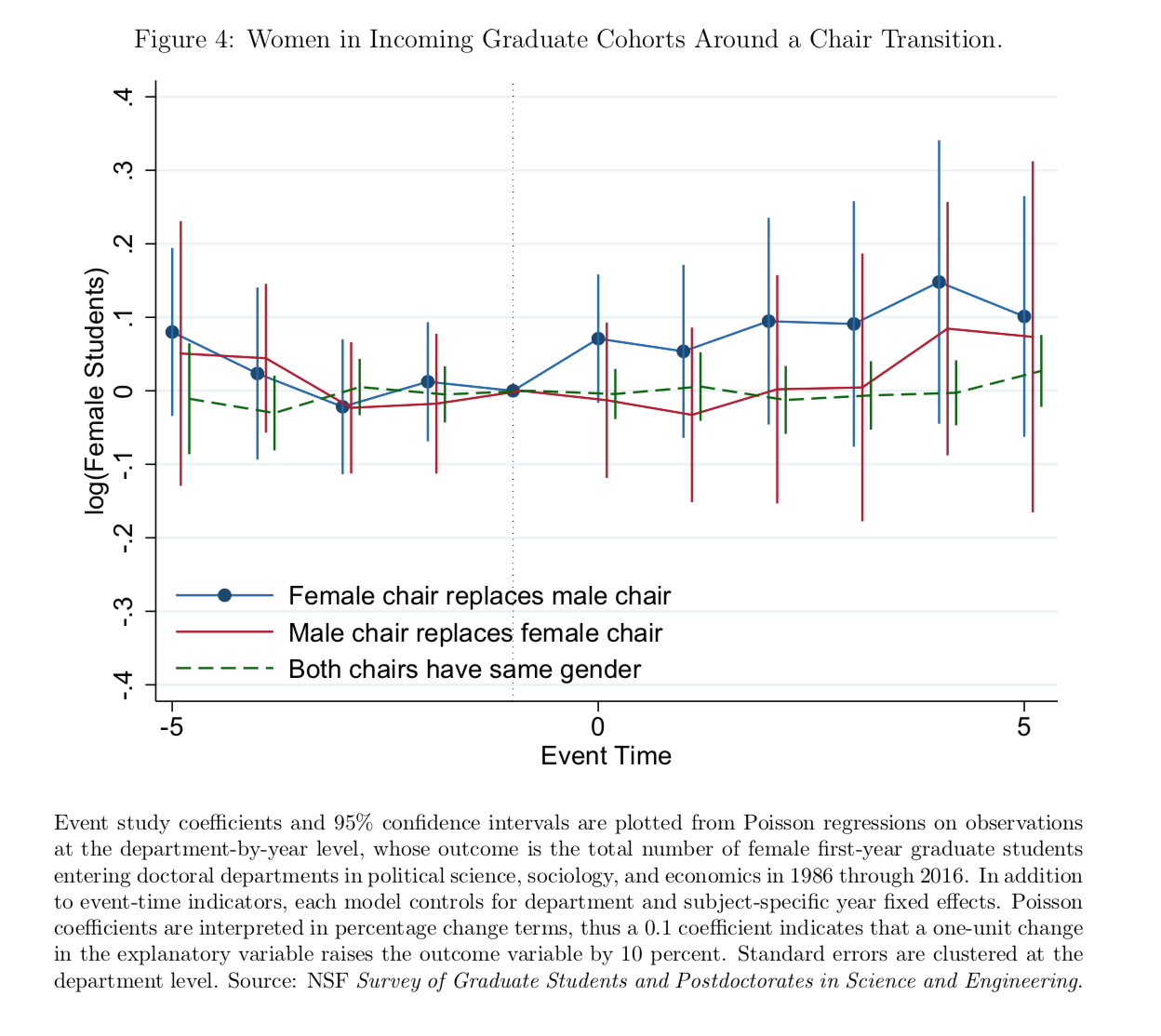

The answer to much of the above is yes, according to a new working paper finding that in departments with female chairs, gender gaps in publication and tenure rates are smaller among assistant professors. The pay gap also shrinks. After departments replace a male chair with a female chair, they see an increase of about 10 percent in the number of incoming female graduate students, with no change in students’ ability levels.

Yet the takeaway is not that it’s “always necessarily better for a woman to work in a female-chaired department, or that chairs show favoritism towards individuals of their own gender,” the paper cautions. Rather, it says, the results reinforce other findings suggesting that “managers from different backgrounds often take different approaches, highlighting the value of diversity among decision-makers.”

Further work is needed to understand the management practices that may “help all individuals and academic departments achieve their full potential, regardless of gender or other characteristics.”

The paper, “Female Managers and Gender Disparities: The Case of Academic Department Chairs,” was written by Andrew Langan, a Ph.D. candidate in economics at Princeton University who has previously found that graduate economics programs with better outcomes for women tend to hire more female professors, enable adviser-student contact, offer “collegial” research seminars and employ senior faculty members who are aware of gender issues.

Langan said this week that he wanted to study female department chairs in particular because academe is, “in many ways, an ideal setting to look at the impacts women have in management and how they differ from men.” That’s a major of area of research with many unanswered questions, he added, and academe is an “especially nice place to look for answers.” Why? Academe has long-run data on individuals' background and outcomes, to often include public salary data.

From a policy perspective, there’s big “interest at universities in reducing gender and other disparities in things like pay and promotion,” he said. And government, business and academe alike seek to increase gender balance in certain fields.

What A Chair Does

Langan said his results indicate that “something about how the department is managed actually matters,” whoever the chair happens to be. Again, these results don’t seem to merely come from having a female chair, but rather what that chair does, he said.

“I think departments who are interested in changing their outcomes would do well to take that into account, and to look at their practices.”

For his study, Langan collected a database of department chairs in economics, accounting and political science across nearly 200 institutions, spanning 35 years. (He estimates that his paper represents the largest compilation of faculty rosters to date.) He then examined cross-department variation in the timing of transitions between department chairs, along with variation within a department of the chair's gender over time.

Among assistant professors, working more years under female department chairs is associated with smaller gender gaps in publication and tenure rates. The wage gap across a department also shrinks in the years after a woman replaces a man as chair. And female chairs raise the number of women in incoming graduate student cohorts without affecting the number of men, or proxies for ability.

Source: Langan

Interestingly, Langan found no increase in women’s representation on the department faculty under female chairs. There was also no effect, either way, of a female chair on the number of top papers published per person at the department level.

As to why female chairs appear to have some positive effects, Langan in his paper guesses that chairs act as mentors or role models “and steer the culture and tone of the department.” Having a female role model as chair might “increase women’s demand for spots on the faculty or in the student body,” he adds. That assertion is supported by many other studies on role models. But Langan said more is at work than seeing oneself in a mentor, namely the chairs’ wheelhouses: dividing and negotiating for departmental resources, staffing admissions committees, and dealing with professors who have received outside offers.

Langan's paper includes an advanced analysis to estimate the change in gender representation that would result from a policy that replaced some male chairs in economics with women. Even a major effort to replace male chairs at 25 percent of departments would result in “fairly small impacts on the number of female faculty 20 years in the future, relying on mechanical effects alone,” he says.

“So while female chairs meaningfully increase gender equity in outcomes, this exercise suggests some other important factors lay behind long-run demographic shifts observed in some fields.”