You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

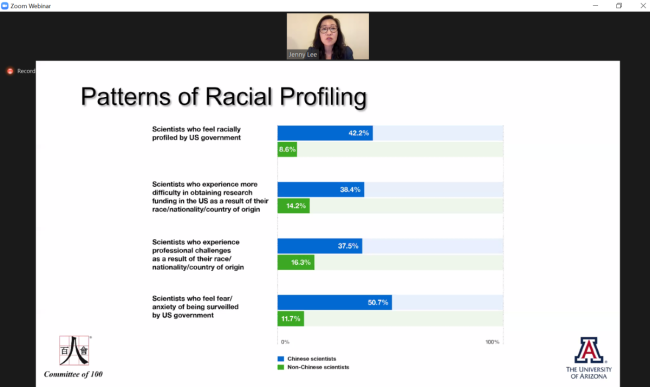

Jenny J. Lee, a professor at the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona, presents survey research Thursday.

Screenshot by Elizabeth Redden

Some U.S.-based scientists are withdrawing from collaborations with Chinese scientists due to concerns such engagements could attract scrutiny from federal prosecutors, according to a new survey finding evidence that the U.S. Department of Justice’s China Initiative is having a chilling effect on scientific research.

A growing number of scientific groups and civil rights organizations have raised alarms over the past year about what they see as racial profiling of scholars under the China Initiative, a Department of Justice program launched by the Trump administration.

Ostensibly aimed at targeting economic espionage and trade-secret theft, the initiative has fueled unprecedented scrutiny of researchers’ scientific ties to China. About a dozen university-based academics have been charged under the initiative for fraud-related charges, typically based on accusations they lied about Chinese affiliations or funding sources on federal grant applications or other federal forms.

Apart from the criminal prosecutions, federal scientific agencies including the National Institutes of Health have launched probes into whether scholars are disclosing their foreign affiliations and funding sources, with most of the investigations focusing on China. Scientists have lost their jobs as a result.

“There is indeed a chilling effect,” said Jenny J. Lee, a professor at the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona who led the survey, which was commissioned by the Committee of 100, a self-described “leadership organization of prominent Chinese Americans” working in academia, business, government and the arts.

“Others have speculated on that before, and now we have empirical evidence that it is affecting everyday scientists, Chinese and not Chinese, in different ways,” said Lee, whose research focuses on the internationalization of higher education, scientific collaborations and issues of neo-racism and neo-nationalism. “This is actually undermining the U.S.’s ability to be globally competitive. We’re finding that scientists are less likely to collaborate with China, less likely to host Chinese scientists, less inclined to apply for federal funding, which means smaller projects, and more inclined to work in domestic teams.”

“Additionally concerning,” Lee said of Chinese scientists, “they are less inclined to stay in the United States.”

The survey, which was sent to scientists, including professors, postdoctoral fellows and graduate students, at 83 highly ranked universities in the U.S., found that 42.2 percent of Chinese scientists feel racially profiled by the U.S. government, compared to 8.6 percent of non-Chinese scientists.

Chinese scientists -- for the purposes of the survey, the term “Chinese” referred to any individual of Chinese descent or heritage, regardless of citizenship -- were more likely than non-Chinese researchers to say they experienced difficulty obtaining funding in the U.S. due to their race, ethnicity or national origin than non-Chinese researchers (38.4 percent versus 14.2 percent). And slightly more than half (50.7 percent) of Chinese scientists reported feeling considerable fear and/or anxiety that they were being surveilled by the U.S. government, compared with only 11.7 percent of non-Chinese scientists who said the same.

The survey found evidence of reluctance on the part of the U.S.-based scholars -- in particular those of Chinese heritage or descent -- to work with scholars based in China. Among Chinese respondents, 19.5 percent reported having prematurely or unexpectedly ended or suspended collaborations with scientists in China over the last three years, compared to 11.9 percent of their non-Chinese counterparts. The top reason cited was a desire to distance themselves from collaborators in China due to the China Initiative (61.2 percent).

Among Chinese respondents, 78.5 percent cited the China Initiative as the main reason for ending their Chinese collaborations, while among non-Chinese respondents, just 27.3 percent cited the DOJ initiative.

The survey also asked non-U.S. citizen scientists about their plans to stay in the U.S. Among non-U.S. citizen scientists in the sample, 42.1 percent of Chinese scientists said the China Initiative and related investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation have affected their plans to stay in the U.S., compared to 7.1 percent of non-Chinese scientists.

A report about the survey includes quotes from respondents, including U.S. citizen respondents, questioning their plans to stay in the U.S.

“I was born in China, and became a U.S. citizen,” said one respondent, identified as a Chinese American professor of astronomy. “I would never do anything that betrays or harms the U.S. I have been successful in my career because of the U.S., for which I am grateful. I want to build a bridge between the U.S. and China so that the two countries can collaborate in science and live in peace. But the ‘China Initiative’ makes me think that I may not belong to the US, and motivates me to move back to a position in China at some point. (I do have a lot of opportunities in China).”

A Chinese associate professor of chemistry wrote, “As a Chinese professor who is trained and has been working in the US for nearly 20 years, these investigations and restrictions against Chinese scholars make me feel unwelcome and somewhat discriminated and I sometimes feel my Chinese identity may be the limiting factor for my career advancement in the U.S. In the past few years, I felt for the first time since I have been the U.S. that Chinese scientists are not valued as much as before and politics is intervening in academic freedom. This makes me seriously consider moving to China if the current trend continues or even worsens.”

The report also quotes scientists, both Chinese and non-Chinese, who reported limiting collaborations with Chinese scholars to limit potential risk -- or hassle.

“The atmosphere in the U.S. [is] making collaboration with China complex and somewhat risky, so many U.S.-based researchers now avoid it to avoid the hassle,” said one non-Asian professor of environmental science.

The report also says “numerous” respondents “described a detriment to their research projects and productivity … Some indicated a change in their research topics and plans towards those deemed less sensitive … Some scientists reported less interest in applying for federal grants, as NIH [National Institutes of Health], for example, was repeatedly noted as a threat in over scrutinizing collaborations with China. Others wrote that they would only work in domestic teams. And others indicated limiting their work to open-source data.”

The Department of Justice did not respond to a request for comment Thursday.

Justice Department officials have previously defended the initiative, rebutting allegations of racial profiling and justifying the focus on China in light of what they have described as the unique scope and scale of Chinese government programs aimed at stealing sensitive technology. They also have defended the decision to prosecute alleged nondisclosures of Chinese affiliations and funding sources on grant applications and other federal forms, saying that lying to the federal government is a crime and there is no carve-out for professors.

The Justice Department has had a string of legal losses related to the initiative in recent months. Just last month, a federal judge acquitted a University of Tennessee at Knoxville professor who was accused of lying about an affiliation with a Chinese university on a National Aeronautics and Space Administration application. And in July the department dropped cases against five visiting Chinese researchers accused of lying about ties to the Chinese military on visa applications.

Many of the researchers who responded to the survey expressed confusion about their university’s disclosure policies. The survey found that 24.7 percent of Chinese scientists and 20.2 percent of non-Chinese scientists said their academic institution had not provided clear guidelines on how to report conflicts of interest.

The survey sample consisted of 658 Chinese and 782 non-Chinese scientists, and another 509 scientists who did not report their racial or ethnic background. The response rate for the survey was 6.8 percent.

Lee said she received inquiries from Chinese scientists after the survey was distributed questioning whether it was real or whether it was a trap set by the federal government. Chinese colleagues she knew personally told her they completed the survey because of their personal connection, but they otherwise would not have participated. One survey respondent admitted to changing answers due to concerns about entrapment. Together, she said, these experiences suggest some survey respondents may have self-censored and underreported the extent of the problems.

Lee presented the research Thursday evening at an event that featured prominent university leaders and scholars.

“The last few years have been particularly difficult for Chinese and Chinese American scholars in the U.S.,” Stanford University president Marc Tessier-Lavigne said during Thursday’s event. “I remain deeply concerned about the uptick in acts of racism and hate directed toward people of Asian descent throughout the pandemic, and I’m equally alarmed that Chinese and Chinese American scholars and students report feeling increased pressure and scrutiny of their academic pursuits, much of it triggered by policies in Washington.

“In recent years policy makers have raised concern about the potential for misappropriation of intellectual property,” Tessier-Lavigne said. “Universities have a responsibility to attend to these issues, but it’s also essential that these concerns are handled in a way that preserves our ability to collaborate on important research.”

Zhengyu Huang, president of the Committee of 100, said the China Initiative, it “has ushered in heightened suspicions about scientific collaborations with China.”

“In the African American community, there’s a term, ‘driving while Black,’ that refers to African Americans being pulled over by police at a much higher rate because of the color of their skin,” Huang said. “In the Chinese American community, we now have a comparable saying -- ‘researching while Chinese American’ -- that refers to scientists of Chinese descent who are more likely to be suspected of spying for China simply because of their ethnicity or national origin.”