You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Some institutions, like the University of Texas at Austin, have had record enrollment this fall. Others are still struggling.

Xianghong Garrison/iStock Editorial/Getty Images Plus

After a bruising year of pandemic-related enrollment declines, higher education leaders across the country are anxiously waiting for this fall’s national enrollment picture to emerge.

Many of the signs suggest at least modest improvement over all, but with wide variation among sectors and institutions. National Student Clearinghouse data released in May showed the enrollment downturn slowing, but by no means reversing. The NSC is scheduled to release nationwide enrollment data for fall 2022 later this week. As the fog of the pandemic’s impact clears, those numbers could reveal the contours of a new landscape for higher education.

Enrollment officials at colleges that experienced robust increases aren’t even waiting for the official numbers and are instead publicly announcing enrollment upswings. Administrators at colleges that had modest gains are being more circumspect and have adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Meanwhile, those institutions where enrollments continued to decline are likely keeping that news to themselves.

“University of Arkansas enrollment is booming,” Charles Robinson, interim chancellor at Arkansas, said of the university’s preliminary numbers in a press release. Enrollment increased 8.3 percent compared to last year, and first-year enrollment rose 17.1 percent. “We have record overall enrollment and highest ever new freshman enrollment.”

While the pandemic certainly played a critical role in depressing enrollment rates, the declines also partly reflect long-term demographic shifts.

“We’ve had a long stretch now of declining matriculation rates. COVID amplified that and produced disproportionate deviations in other trends. That makes the numbers we’re going to see really interesting,” said Nathan D. Grawe, the author of Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education and The Agile College (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018 and 2021). He added that because government pandemic relief funds have stopped flowing, “it becomes important in a way that was a little bit less true for the last two years that colleges make their enrollment goals” and make up for lost revenue.

Enrollment seems to be a mixed bag this fall as preliminary numbers roll in from institutions and systems across the country. While some are reporting record first-year classes and enrollment increases, others face stunted growth or worsening declines.

“There are roughly 4,500 colleges and universities in the United States, so there are roughly 4,500 stories about fall ’22 enrollment,” said Terry Hartle, senior vice president of government relations and public affairs at the American Council on Education.

Some stories are more disheartening than others. One particularly troubling enrollment trend exacerbated by the pandemic, Grawe said, is the decline of underrepresented groups—specifically Black, first-generation and low-income students.

“These groups that have more tenuous connections to higher ed are exactly the groups you would hope to penetrate more if your response to declining demographics were to increase access … and yet, these are the groups who stepped away during the pandemic,” Hartle said. “Seeing whether those groups come back in force is going to be really important as we look forward and think about the work that needs to be done.”

Data from this year’s FAFSA applications offer some hope for at least a partial pandemic recovery, especially among minority and low-income students who did not enroll during the pandemic. There was a 4.6 percent increase in FAFSA applications from high school seniors from 2020 to 2022; at high schools that primarily serve Black and Hispanic students, there was a 9 percent increase in FAFSA applications over the last year alone.

“I think much of higher ed is hoping that the rebound we saw in the 2022 FAFSA cycle will bear fruit this fall,” Grawe said. “I’m sure it will bear some fruit … but we have to see whether that’ll turn into enrollments getting back to pre-pandemic levels.”

New Paths to Growth

Some large public university systems, especially campuses that are more selective and have strong academic reputations, are reverting to the positive matriculation rates they had before the pandemic.

“Selective schools have done very well,” Hartle said. “The enrollment at those institutions continues to climb.”

But some public institutions that aren’t necessarily household names have also come out on top this fall. Hartle said that colleges and universities in states such as Texas and California, where populations are growing, seem to be faring better than their counterparts in states facing demographic cliffs.

This past spring, the University of Texas system—one of the largest in the country—saw 2 percent total enrollment growth, despite a national dip of almost 3 percent.

The University of Texas at Austin welcomed its largest incoming class this fall, 9,109 students, and had a record total enrollment of 52,384 students, surpassing its peak of 52,261 students in 2002, according to a news release from the university. The university also reached its highest-ever Hispanic enrollment, making up 27.9 percent of the undergraduate student body. Now 33.6 percent of undergraduates and 30.3 percent of all students come from underrepresented backgrounds, another record for the institution.

Some big publics that were struggling are still seeing overall declines, but the trends look to be reversing, especially with first year enrollment.

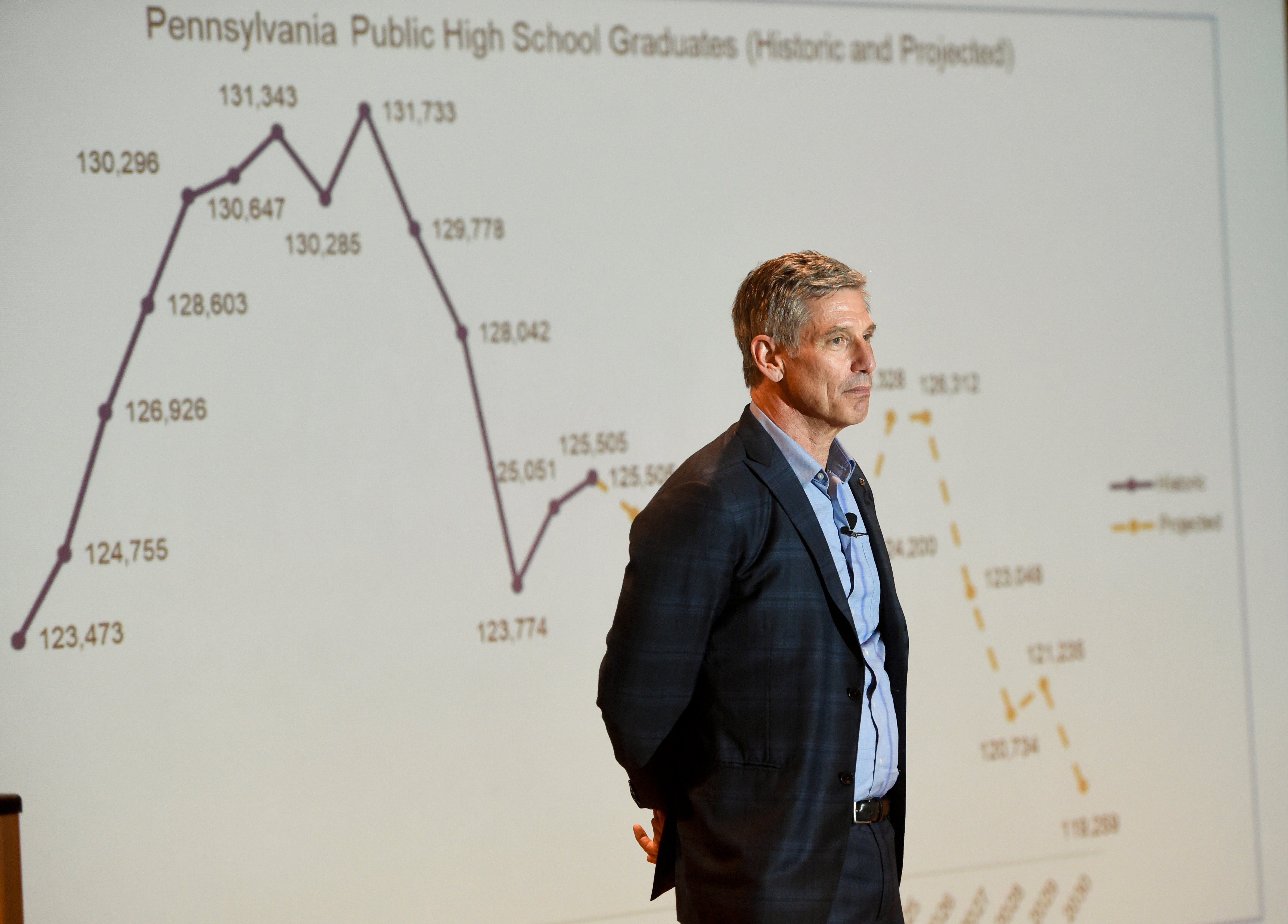

Enrollment in the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education fell almost 5 percent this fall relative to the year before, but enrollment of first-time students grew 7 percent, the largest increase in freshmen the system has seen in over a decade. If that growth in first-time students holds steady, Chancellor Daniel Greenstein estimates the system could stop its long-standing trend of declines in four years.

Greenstein partly attributes the surge of freshmen to system leaders holding tuition flat for the last four years and increasing financial aid. He also praised campus leaders for their efforts to expand online program offerings in high-demand fields to attract adult learners.

“You’re seeing all sorts of really interesting pathways that are really designed for working learners to come in and out … and continue to build their credentials,” he said.

Greenstein believes as the number of high school graduates declines in the state, public four-year institutions will have to market to a wider range of students, including students who started college but never graduated or students looking for fast credentials rather than traditional degrees.

“There’s no way to fill that gap on the back of what I’m going to call traditional students, high school age,” he said. “And there’s no way to fill that gap on the back of students who can afford the relatively high price of higher education. You’ve got to figure out a way to open the aperture.”

The pandemic has given some long-struggling public institutions an opportunity to shift gears and develop new strategies for opening that aperture.

After 14 years of steady enrollment decline, leaders at Western Illinois University knew something needed to change. The overhaul came in 2021, with a new president and a slate of fresh administrators.

One of them is Amber Schultz, WIU’s first vice president for enrollment management. She said in order to boost enrollment, the university had to get smarter and more serious about recruitment. (Editor's note: This paragraph was revised to correct a name.)

“We’re not just facing fierce regional competition because of the demographic decline; now we’re also facing competition from employers, because the message to high school graduates from employers in western and central Illinois is, ‘we need you right now,’” she said. “So we realized that if enrollment is our biggest vulnerability and priority, it needs to be one of our main focuses.”

The effort paid off: WIU had a 2.5 percent overall enrollment bump and a 16.7 percent increase in freshman enrollment this fall. It also enrolled more than 1,000 international students, the most in the institution’s 123-year history.

Finding a Foothold as Cliffs Loom

Other public systems are still struggling more than their leaders expected because the pandemic exacerbated the impact of already-worrisome demographic trends.

Robert Placido, vice chancellor of academic affairs at the University of Maine system, said the demographic cliff has been a looming concern for a decade. Still, the almost 6 percent decline across the system this fall, compared to prior to the pandemic, was steeper than he predicted. The system’s most recent enrollment data show student head count fell to 24,817 this fall from 26,394 students in fall 2019.

Part of the problem is that college-going rates among the state’s already dwindling high school graduates fell during the pandemic, Placido said. The share of Maine high school graduates who enrolled in college immediately after graduation had hovered around 66 percent since 2014, according to data from the New England Secondary School Consortium. That share fell to about 55 percent in 2020.

“We absolutely believe COVID is a factor in this—the stunting of the social development of our kids in high school, isolation, anxiety disorders, mental health issues,” he said. He added that high school graduates are eager to take jobs and save money, especially those from families that struggled financially during the pandemic.

Some campuses in the system have fared better than others. Placido noted that rural institutions are struggling more than their urban counterparts. For example, head count at the University of Maine, the state’s flagship, fell 5.1 percent this fall compared to last fall, while University of Maine at Fort Kent suffered a 16.1 percent loss.

However, enrollment in the system’s online programs more than doubled in the last two years. Placido hopes online offerings will attract adult learners as the number of traditional-age students wanes. System administrators also plan to double down on efforts to recruit out-of-state and international students, especially those from nearby Canada.

The growth in online students has been one predictable outcome of the pandemic, though that’s often little consolation for public institutions that are also seeing their more lucrative in-person enrollment decline on ever-steeper gradients. At William Paterson University in New Jersey, matriculation rates fell by over 10 percent this fall; meanwhile, enrollment in its online programs, collectively known as WP Online, grew by 57 percent.

“Our online growth is good news and a testament to the quality and appeal of our offerings,” the university’s president, Richard Helldobler, wrote in a letter to faculty. “However, the full-time, main campus population is the biggest source of revenue, so reversing these declines is imperative.”

Across the Washington State University system’s five campuses, enrollment dropped by almost 8 percent this fall. The drop-off was largely due to a steep decline in transfer enrollment. At WSU Pullman, the system’s flagship campus, freshman enrollment was higher than it had been in four years, but transfers were down by 20 percent. The result was an overall enrollment drop. Two other campuses, WSU Everett and Spokane, experienced close to a 30 percent drop in transfers.

The system’s struggles reflect a broader, troubling trend in transfers from two-year colleges to four-year institutions nationwide, but it’s particularly pronounced in Washington State, where community and technical colleges experienced a 24 percent drop in enrollment from 2019 to 2021.

Saichi Oba, the WSU system’s vice president for enrollment management, said public universities that rely on community college student transfers have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic.

“We were feeling pretty good right up until about the beginning of the term,” Oba said. “That’s been an important indicator of where COVID’s effects are lasting for us—namely in the ripple effects from community college declines.”

Washington’s public universities were already struggling with low interest from in-state students before the pandemic. Despite having one of the most generous state-run financial aid programs in the country, only 60 percent of high school students in the state enrolled in college in 2020, which is below the national average. Of the students who did enroll, only about half enrolled in a four-year college.

“There’s not really a college-going culture here,” Oba said. “Washington has invested a great deal of resources into helping families pay for their education, and yet we’re still having a difficult time breaking through the barrier.”

Oba said that means the competition is stiffer than ever for local applicants, and recovering from the loss in transfers is going to be crucial moving forward.

“We have to show that the investment is worth it,” he said. “Our focus is going to be on transfers, because the decline was so precipitous this past fall that we’re gonna have to work doubly hard just to get back to even.”

Hard-Hit Community Colleges Shift Gears

Community colleges suffered especially staggering losses during the last two years, in part because they disproportionately serve low- and middle-income students whose enrollment took a “deep dive” during the pandemic, Hartle said. Students are also increasingly choosing jobs over college as employers raise wages to attract workers and fill labor market shortages.

Russ Deaton, executive vice chancellor for policy and strategy at the Tennessee Board of Regents, said adult learners have left Tennessee community and technical colleges in droves. The state system enrolled 70,313 students this fall, 18,633 fewer students than 2019, according to preliminary data provided by the system. Enrollment is at its lowest since 1990, and the number of adult learners in the system dropped a staggering 30 percent between 2019 and 2022, a development Deaton finds “really troubling.”

“You can make decent wages in certain entry-level, customer-oriented jobs … I think that’s probably changed students’ calculus a bit,” he said. “The economy is offering wages that it did not just a few years ago.”

But he also highlighted some “bright spots” in the preliminary data, including growth in the Hispanic student population. Ten colleges made gains this fall in Hispanic enrollment, which rose 8 percent over all across the system compared to last year. The number of dual-enrollment students also increased by 1 percent compared to prior to the pandemic, and dually enrolled high school students outnumbered freshmen in the system for the first time.

“I was an optimist early in the pandemic about enrollment, and then reality set in and we’ve had declines ever since,” he said. “But I’m still optimistic long term that we’re going to turn it around.”

Some community college systems have started to recover but still have a long way to go before they reach pre-pandemic enrollment numbers. The number of students attending Colorado community colleges increased about 3.5 percent this fall compared to last, but that doesn’t make up for the almost 16 percent drop in head count since 2019, said Joe Garcia, chancellor of the system. Students are also taking fewer credit hours in order to have more time to work.

“The bad news is the areas where we saw the biggest loss, and still do, are among the lowest-income students and students from communities of color,” Garcia said. “We had been working for decades to make progress—we did make progress—but we’ve lost a lot of that progress over the last two, three years.”

He believes some statewide efforts are helping to bring these students back. State lawmakers launched CARE Forward Colorado this fall, which uses COVID-19 relief dollars to cover tuition, fees and books for a range of short-term certificate programs in health-care fields at Colorado community and technical colleges. Garcia said the short-term, free programs are a draw for students who want to swiftly get back to the workforce in a strong economy.

He said community colleges nationally are increasingly competing with more selective universities for the kinds of students two-year institutions historically enrolled in large numbers, such as adult learners and low-income students. He’s heartened, however, to see universities working to attract and support these students.

“Those name-brand institutions see the demographic changes, that writing on the wall, and they’re going after students who previously they just would have assumed would come to one of the open-access institutions and they weren’t really targeting them,” Garcia said. “Now I really do think the competition for bodies has caused some of those more selective institutions to adopt a broader view of who could be successful at their particular university.”

Private Colleges Branch Out to Stand Out

The most troubling enrollment story of both the pre- and post-pandemic eras is that of small private colleges, mainly in the Northeast and Midwest, beset by shrinking applicant pools and surrounded by similar competitive institutions. The pandemic pushed many of them over the financial brink.

Some of these institutions successfully filled their classes last year. But the latest National Student Clearinghouse data show enrollment at private nonprofit colleges over all fell 1.7 percent in spring 2022 compared to the year before, putting private college leaders on edge ahead of this fall.

“I think that the 2025 demographic cliff a lot of people in the field talk about, the pandemic has actually sped that up,” said William Bisset, vice president for enrollment management and student affairs at Marymount University, a private Catholic institution in Virginia. “I think we’re starting to see that happen sooner than expected.”

Grawe said one notable exception to the demographic decline has been in Hispanic students, who are “steadily becoming a bigger part of the higher education market.” A Pew Research Center analysis released this month noted that Hispanic enrollment more than doubled in the last two decades, growing from 1.5 million in 2000 to 3.8 million in 2019.

But he added that certain institutions have been more likely than others to capitalize on this.

“It’s interesting to note that, disproportionately, this convergence has been driven by the public four-year sector, which suggests that some other parts—the private four-year sector, for instance—are missing out on opportunities.”

Marymount is not among those colleges. Last year it became the only federally designated Hispanic-serving institution in the state after surpassing the threshold of a 25 percent Hispanic student body. This fall the university saw an 11 percent increase in first-year enrollment, Bisset said.

While it’s hard to draw a conclusive correlation between the two, Bisset said it’s clear that the institution benefited from focusing on the Hispanic and first-generation markets, which helped offset the effects of other pervasive demographic declines and pandemic-related retention challenges.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence that in the first year of our designation, we saw a 41 percent increase in applications, many of them from completely new markets,” Bisset said. “There are people in the college counseling world reaching out to me who’d never heard of Marymount before, and applicants from areas of the country we’d never seen.”

Chris Domes, president of Neumann University, a small private Catholic institution in Pennsylvania, also believes his university was spared the declines faced by some other small private institutions thanks to its focus on underrepresented students.

Enrollment at Neumann fell from 2,506 students to 2,212 last year, but it held steady this fall, and first-year enrollment rose 9.5 percent compared to last year. The majority of the freshman class, 63 percent, are first-generation college students. About 40 percent of the student body are students of color, and more than 40 percent are eligible for the Pell Grant.

“We serve a big percentage of underserved populations,” Domes said. “The demographic shifts are primarily in white and wealthier communities … We feel the community we’re serving is another piece of headwind against the demographic shift, because those are not where the drops are.”

“I do believe that enrollment management is a science, but it’s also an art form … that’s where getting out there and making the case for your institution comes in,” Bisset said. “It’s never been more important to do that. If you can’t make an effective value proposition for your institution to prospective students, you’re going to have a hard time meeting your enrollment goals.”