You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Truth of micro, lie of macro,

or,

the relative quality of stories

Imagine a certain kind of big-picture story from the American Century:

Son of a struggling Midwestern sharecropper—there’s already been a Fall in prehistory, you see, since it’s known the family is ancient and accomplished, as if these are seeds for future seasons—is born during the Great War, gets a New Deal as a teen, labors through the Depression. Goes to battle in history’s Greater War, on return is educated by a grateful nation. Becomes university faculty himself, serves on educational missions to Vietnam and Afghanistan. Does a sabbatical in Paris at a lost-wax gold foundry, tends to Beirut, advises Indonesia. Moves into administration.

His wife has her own career and is happy in her teaching. She’s also from a family broken in a previous generation—how often this happens in America—but her father did well. She’s known the good life and has been able to build on it. Writes and publishes poetry, takes classes in ikebana and languages. Volunteers as scout leader, nature conservator, humanitarian.

Through it all they love each other and raise three children from several marriages. The children thrive, are educated in turn at their father’s alma mater or their mother’s, or at The Point. They marry well, raise their own children to be strong and confident and to know what’s right and how to negotiate the social order, when to hold fast and when to let go.

The parents retire at an age they choose, are comfortable, healthy, and mobile for many decades. Then, offering wise and comforting words from a century of honorable good life, they die without pain within days of each other, surrounded by generations of loving family.

The United States, by the way, finally realizes and makes peace with its own nature, rights itself, and by most measures eliminates injustice and waste within its borders. It joins other countries, such as Vietnam, where The People are now unified and very happy, in the community of free nations. Human nature is subverted, unspeakable environmental disaster averted, the evaporation cycle turns out to meet all energy needs, and boundless love radiates through the entire world forever.

***

Consider the less epical scope of an article written by a family friend, Bill Bartlett, who worked for the SIU Printing Service and accompanied his wife, Professor Mabel Lane Bartlett of the University School, on the SIU/USOM mission to Vietnam.

“Assignment: South Viet-Nam” appeared in the September 1962 issue of Southern Alumnus. Its occasion was a two-week visit to Saigon (“halfway mark on their recent trip around the world”) by SIU President Delyte Morris, his wife, and son. There, “Mr. Morris familiarized himself with the work of the two contract groups that Southern had sent to the little Southeast Asian country in 1961.” (Photo used with permission of SIU Carbondale.)

“Assignment: South Viet-Nam” appeared in the September 1962 issue of Southern Alumnus. Its occasion was a two-week visit to Saigon (“halfway mark on their recent trip around the world”) by SIU President Delyte Morris, his wife, and son. There, “Mr. Morris familiarized himself with the work of the two contract groups that Southern had sent to the little Southeast Asian country in 1961.” (Photo used with permission of SIU Carbondale.)

The work of these groups was meant to help with specific problems, such as: “The national average of elementary students per teacher is 56; it is not unusual to find 75 pupils in a single classroom. And there are one-half million youngsters of elementary school age for whom there is no place in the schools of the nation.” “At present, few elementary pupils spend more than two hours each school day in the classroom. Hundreds of students crowd around the gates to the city schools, waiting for their two-hour turn in classes.” “The recent rapid trend toward mechanization in Viet-Nam has far outstripped the supply of skilled workers capable of maintaining, repairing, and building modern machinery.”

Progress had been made. “According to recently published Department of Education figures, 1.5 million uneducated Vietnamese adults have become literate during the past seven years. In the same period—1954 to 1961—the number of schools and classrooms increased almost fourfold, with the United States Overseas Mission cooperating in the school construction program.” The article provides details about normal and technical schools in Saigon, Vinh-Long, Ban Me Thuot, Qui-Nhon, Danang, and Hue, and sketches the lives of American teachers and families fulfilling the contracts.

Bill writes with interest and appreciation. He notes the “magnificent abundance” of delicious food in this “cornucopia along the South China Sea,” the “warm hospitality and friendliness of the Vietnamese people,” the “cosmopolitan air” of its capital city. “Saigon streets are glutted with a fantastic assortment of vehicles. Fast, snappy foreign sports cars and long, black limousines of government officials share the tree-shaded boulevards with an unbelievable variety of lesser vehicles: passenger-carrying pony carts, an occasional oxcart, pedicabs, tiny Renault taxis, motorcycles, motor-scooters, bicycles—thousands upon thousands of bicycles which swerve in and out... [All] peacefully co-exist in a surprisingly well-regulated flow of traffic.”

He also drops hints of context, whether unconsciously or pointedly, setting them apart in italicized type, as if there are two stories to consider, one Romanized and one not: “It should be noted that all of this problem [of too few classrooms] cannot be attributed to lack of schools and teachers. The threat of terrorism by Viet-Cong guerillas, particularly grave in the rice-rich region of the south, has made it necessary for many rural schools to close.” “The government troops subdued the [Cholon River] pirates [after they ‘severely damaged’ the Saigon Normal School].”

One of the sections, about downtown housing for team members, is titled, “Behind Bars, Barbed Wire, and Broken Glass.” Where my own family lived “in a residential development in Gia-Dinh province outside Saigon...the entire housing area is protected by a high fence. Along access roads and at the two entrances to the area, Vietnamese soldiers man checkpoints where persons seeking to enter the compound must be identified and cleared. [T]he thunder of big guns and the crackle of smallarms [sic] fire frequently interrupt the quiet of the tropic night...sandbagged gun emplacements are constant reminders that the VTI [SIU’s Vocational Technical Institute] team is living in a nation at war.”

***

Consider Jessica Elkind’s recent Aid Under Fire: Nation Building and the Vietnam War (University Press of Kentucky, May 2016):

American nation builders believed that educational development offered an important avenue for bolstering the state of South Vietnam and for improving the lives of its people. Most aid workers had an idealized vision of the transformative effects of education. They believed that American education models, which emphasized scientific methods and English-language acquisition, could help modernize Vietnamese society, which they viewed as backward and traditional. They also believed that a Western education system might promote stability and economic development in South Vietnam. Such grand ideas about the power of education mirrored the goals of education reform in colonial settings. Like colonial administrators in earlier decades, American nation builders advocated using education as a means of uplifting a foreign population.

[...]

Although most US officials considered educational development to be a lower priority...many believed that reforming South Vietnam's education system might complement other efforts to strengthen the state while simultaneously countering the appeal of communism. They hoped that, by modernizing South Vietnam's education system and increasing access to it, they could help raise living standards and also train administrators and laborers who might work in service of the state. At the same time, they assumed that education might also contribute to their counterinsurgency efforts. In essence, many US officials thought that Americans could teach Vietnam's population to support the Government of Vietnam (GVN) and, by association, the American intervention. Aid workers at the US Operations Mission (USOM) and volunteers from International Voluntary Services (IVS) shared this conviction and eagerly offered their services.

Education advisers from USOM and especially IVS assumed an explicitly political role and served to implement US and GVN policies to a greater degree than most American aid workers in the country.

***

But:

“On September 19, 1967, forty-nine members of the volunteer humanitarian group International Voluntary Services (IVS) resigned from their positions in a letter to President Lyndon B. Johnson, stating that ‘to stay in Vietnam and remain silent is to fail to respond to the first need of the Vietnamese people – peace.’ [...]

...IVS refused to follow the demands or methods of the U.S. military because they ran counter to the mission of IVS, which decided to resist the U.S. government’s demands.”

***

And: I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say the SIU/USOM team risked their lives—all our lives—to do something for the people of Vietnam that went beyond personal ambition or some notion of American hegemony. Later we all try to feel our way through where one thing hazes into another. When exactly does “the merry dance of death and trade” begin?

And: I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say the SIU/USOM team risked their lives—all our lives—to do something for the people of Vietnam that went beyond personal ambition or some notion of American hegemony. Later we all try to feel our way through where one thing hazes into another. When exactly does “the merry dance of death and trade” begin?

As a former soldier, I know how it is to work in a system in which you have no say in the system’s use. We all do. But where does culpability stop? Should the foremen of those who poured concrete for US highways be held accountable for the collapse of small-town business in the interstate era? What about the brainworkers of academe, who sometimes profit by unsavory corporate investments or are complicit in the adjunct industry?

We make our best choices, apply ourselves, and live with the consequences—or else extricate ourselves and start over.

***

But: James Baldwin: 1969:

What must be considered is a final act of the white Christian European industrial drama. Speaking as an American and reading the news and looking at the pictures, the streets of Saigon resemble nothing so much to me as the streets of Detroit, and in both cities precisely the same war is being waged. That war may yet spread to engulf the globe, and let’s speak plainly. We know, everybody knows, no matter whatever the professions of my unhappy country may be that we are not bombing people out of existence in the name of freedom. If it were freedom we were concerned about, then long, long ago we would have done something about Johannesburg, South Africa. If we were concerned with freedom, boys and girls would not, as I stand here, be perishing in the streets of Harlem. We are concerned with power, nothing more than that, and most unluckily for the Western World, it’s consolidated its power on the backs of people who are now willing to die rather than be used any longer. In short, the economic arrangement of the Western World proved to be too expensive for most of the world.

***

“And all The People were Very Happy.”

-- Local guide, over and over, to those taking the tour at the Museum of American War Crimes, Ho Chi Minh City, early 1995, on reunification after the fall of South Vietnam

(NB: After Clinton normalized relations later that year, the prudent Vietnamese changed the name to War Remnants Museum. Change of title, change of story.)

***

One is forced to choose a story, of course. Not choosing is choosing. Keeping belief suspended in the name of rigor and sympathy is, after a time, madness.

***

So: middle-aged newlyweds move their combined family to a strange land. It’s revealed to be the wrong place and time, but they’ve committed in a way that makes return impossible quickly. Their attraction reverses polarity, almost overnight, and no doubt in inverse proportion to its original strength.

Letters, a diary, court documents, articles, photographs--all tell micro stories. Many conflict. Some claim discord, violence (on both sides), abuse, infidelity, cruelty, head games, gamesmanship, and social roleplaying. They imply the cowardice of university administrators, the helplessness of friends and family.

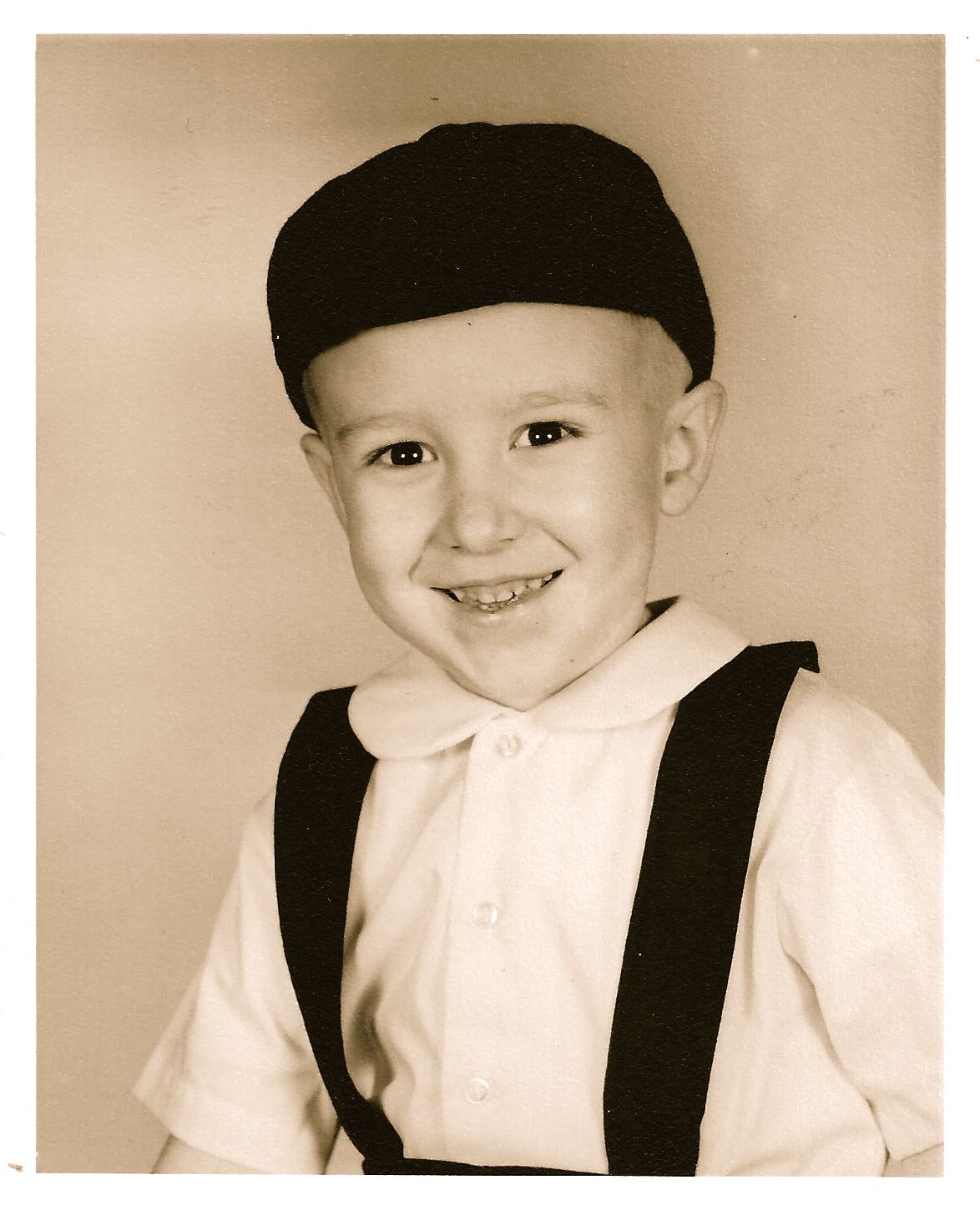

Amid the pain, perfectly literary details. He’d restricted her use of a car, a sore point, so when, two nights before I was born, he “came home with [illegible] white Buick convertible,” she writes: “Had on stupid cap.” Everyone knows that stupid cap. It stands for qualities we’re drawn to, then rage against in disappointment.

The State Department knew of the likely coup against South Vietnamese President Diem; the Kennedys were in support of it. SIU families appear to have been sent home in anticipation of the event. We came back to the States in September 1963; Diem was killed November 2. (JFK, 20 days later.) Supposedly we were meant to go back but didn’t. Then my father was gone for good.

I have a clipping about him from a local paper. The writer stresses that South Vietnam is about the size of the state of Illinois, and that “[d]uring the six dry months the [southern Vietnam] countryside is as dusty as rural Hamilton county has been this fall.” Then, in perhaps accidental free indirect speech, she writes, “The women of Saigon are among the most beautiful in the world, Griswold thinks. She wears the native ‘oua ghai’ (literally meaning long trousers), a practical, graceful long gown with high collar, long sleeves and split skirt work over long trousers. The form fitting gown is concealing yet revealing, feminine in its brocade, and embroidery, silks, and satins. They wear their hair in lovely high fluffs, showing the French influence, and always look well groomed.” The irony may confirm part of the problem.

None of this story is extraordinary, except maybe that stupid cap, and the fact that after the split my parents did paper combat for 13 years. In a strange coincidence, the divorce came about the same time as the close of the war.

None of this story is extraordinary, except maybe that stupid cap, and the fact that after the split my parents did paper combat for 13 years. In a strange coincidence, the divorce came about the same time as the close of the war.

By the end of the story, my father will have had the life portrayed for him at the start of this post. My mother will raise me alone in her hometown, at great personal cost, and her story will go another American way.