You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The funny man* drove down from Chicago last week in a rented jet-black Mustang, looking distinguished and prosperous in his subdued houndstooth jacket, dark jeans, and well-made loafers. It was fitting that the university was the last stop on his 12-city reading tour, since he did his undergraduate degree in English here 20 years ago and at least a couple of his former writing professors would be in the audience.

The funny man is himself now a long-time writing teacher, editor, and author, and the book he’s promoting is his first novel, just out from Soho Press. It’s called, appropriately, The Funny Man, and is a satire about a “middling” comic who scales the heights of fame and fortune when he develops a new act: Fist in mouth to the wrist, then impressions, which of course all sound alike. American audiences go apey for him.

At the start of the book he’s beyond all that and on trial for murder. His family has left, and he’s lost everything. But he’s in a better mood than you might expect, since something new and good is happening to him—there are second acts in American lives, apparently—unless he’s lost his mind and has taken us with him. The titular character goes unnamed; he’s just the funny man, which has echoes of The Falling Man, the everyman of our time, as there are many ways to fall now. The novel is both wonderfully comic and uncompromisingly dark.

In addition to reading at the campus bookstore, the real-life funny man was scheduled to participate in the creation of a fine-arts broadside from his work, visit creative writing classes, and attend a luncheon and a faculty dinner party held in his honor. He would perform all these tasks over two long days admirably, apparently happily, and with an unfailing sense of humor, considering he had pneumonia and wouldn’t know it until he’d left and was on the way home.

I caught up with him while I was walking through Greek Row on my way to the Soybean Press, where he was scheduled to watch the first of his broadsides being run. I looked up at an intersection, and the funny man was in his Mustang at the stop sign, struggling to roll down the window. He looked funny sitting there struggling in his lavender dress shirt, jacket, and wraparound shades, like a performer who can’t get the mike stand to cooperate and knows the audience is waiting. I stood applauding his return. He looked at me through the tinted glass.

“Hop in,” he said, when he’d finally gotten the window down. “I want to drive around a little.” We drove past his old fraternity—the building he’d lived in had been knocked down and a new one erected—and then through campustown, where students jammed the sidewalks on their way to morning classes.

“Murphy’s is still there,” he said, pointing.

“Zorba’s burned down though.”

“Yeah, a student told me that.” He leaned forward and peered out the windshield, distracted as returning alums often are by a flood of memories.

We finally pulled up to the Printing Services building on the edge of campus, out past the stadium. I expected to meet at least one other person from the English Department there, but we went in, got our badges from a secretary, and were led directly up to a quiet pressroom where Steve Kostell and Marten Stromberg of The Soybean Press were waiting to welcome the funny man. They wore printers’ aprons and were surrounded by many silent tons of modern presses made for huge jobs.

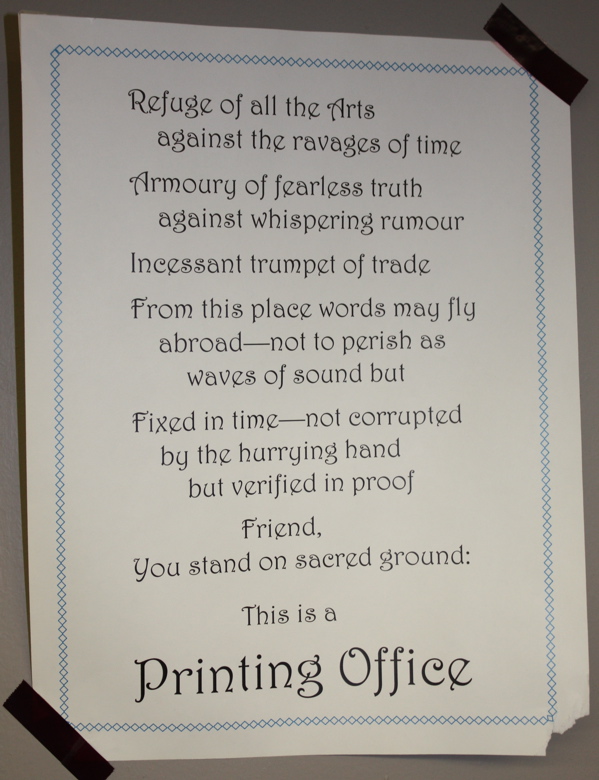

.JPG)

The funny man made small talk with Steve and Marten as they completed the make-ready on a small letterpress. Soybean inherited from the university both iron hand-presses and mid-century letterpresses, and it was one of the latter that would print the funny man’s limited-edition broadside on heavy art paper.

Steve explained that The Soybean Press is the brainchild of Valerie Hotchkiss, Head of the Rare Book & Manuscript Library. They teach classes “to expand knowledge of the traditional art of printing, while incorporating digital technology and other contemporary approaches to print-making.” He said the uni’s Printing Services unit had closed this past summer, and Geology would take over the enormous building.

“So for now, we’re squatting,” he said and laughed. “But it won’t be easy to get us out. We’ve got weight on our side.” He waved at the Heidelberg and other commercial presses, compositors, and mysterious, dangerous-looking machinery now sitting idle. He and Marten joked about getting in on the ground floor of a growing industry.

“In case of electromagnetic pulse weapon, you’ll be the guys, ” the funny man said.

Steve said there are a few book arts programs around the country—Iowa, Alabama, Wisconsin—but they’re often found in different departments. Soybean is a cooperative effort of The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, The School of Art + Design, and The Graduate School of Library and Information Science. The press has worked with student literary groups, visiting artists (such as the Combat Paper Project), authors (Audrey Niffenegger, Time Traveller’s Wife), and internationally-known poets (W.S. Merwin). This year they began partnering with the Creative Writing Program to print broadsides for the Carr Reading Series visitors. The funny man was one of them.

“Is it walking off?” Steve said, holding up the first sheet, about the size of a piece of poster board. The text on it was an excerpt from the funny man’s new novel, in two columns. Marten looked at it with the printer’s meticulous eye. “Yeah.” They ran it again and then again, unsatisfied with tolerances invisible to the layman.

“We’re getting it so it registers on the second side,” Marten said apologetically.

“This is where the deckled edge starts to haunt me,” Steve said.

They consulted again, intent on their problem and ignoring us. The funny man recalled seeing complaints about deckled edges on Amazon reviews of Toni Morrison’s Love. Some readers had never seen them before and thought they were a mistake. Sometime after that, he said, Amazon started posting warnings on the pages of books with deckled edges.

They consulted again, intent on their problem and ignoring us. The funny man recalled seeing complaints about deckled edges on Amazon reviews of Toni Morrison’s Love. Some readers had never seen them before and thought they were a mistake. Sometime after that, he said, Amazon started posting warnings on the pages of books with deckled edges.

“I’m going to clean the plates and try again,” Steve said. He put down the first flawed sheets.

The funny man admired them. “What font is this?” he asked.

“Bodoni.”

“How do you choose your fonts?”

“Dynamic aesthetic,” Steve said.

“You got some nice serifs on there,” the funny man said.

Marten explained they’d had three jobs that week, so they had already used a lot of their cold type. The funny man’s type was set with a custom-made magnesium plate, which would be donated to University Archives after the print run. This seemed to please the funny man. The funny man thought to tell a humorous anecdote about editing profanity from the passage, just for the broadside, so his mom could hang one on her wall.

The two printers cleaned the press, re-inked it, and ran sheets through eight or ten times, painstakingly checking each one for flaws. The funny man yawned a little behind his hand. There was an early morning feel to the place, and no coffeepot. I asked the funny man if he’d discovered that he’s a beach guy, now that he’d moved recently to the coast. He said he never liked laying out or doing beachy things. “But I have to say, it’s awfully nice to walk on the beach near sunrise and watch the world wake up.”

“Looks good,” Steve said. “Now we can start printing them.” He explained they’d do a run of 40. Half would be mailed to the funny man to give away as he liked. The rest would be put up for sale on their website—they hoped to have a physical space in the campus bookstore soon—and a few would be “clamshelled” with other examples of the Press’s work for display.

Steve fed each sheet by hand onto the rotating drum cylinder, which made the impression against the plate; Marten took them off carefully and lay them out to dry, end to end, on long white tables. Later the sheets would have to be run through again to imprint the colophon that would appear on the second side.

“What do you do if the press breaks down?” the funny man asked. Steve explained that Fritz Klinke—“great name, right?”—an older man who lives in Colorado had bought all the copyrighted manuals for the press they were using that day and was one of the few press mechanics around. “I’m a bastard printer,” Steve said, “and I rely on people like Fritz. A true letterpress craftsman. He had a heart attack, but he’s still working.”

Steve said the Press hoped to get increased funding, maybe an endowment, to create an entire curriculum and hire a shop manager who could focus only on the operations of the Press.

“Institutional memory,” the funny man said.

“Right. Because the goal is to make art accessible. It’s still a precious object, but not to the point of being unattainable. Raise the awareness of art printing and literature.” He said there were many ways to have printed material, and they didn’t have to be mutually exclusive. He mentioned the campus bookstore’s new print-on-demand book dispenser and was excited by the application for reading copies.

They cut the funny man loose when they had a dozen or more of the oversized sheets drying on the white tables. He’d go back the next morning to sign them before he left town.

At lunch the funny man ordered the venison risotto. Those present included 2½ of his former teachers. One of them told a story about his house being TP’d the night before. He had found one of the culprit’s bicycles, TP’d it to look like a mummy’s bicycle, and left it at the curb. It turned out to belong to his daughter’s boyfriend, who wasn’t even involved.

“That’s irony,” the funny man said graciously. His former teacher graciously declined to suggest it wasn’t irony. The funny man smiled when the professor pulled out his credit card to pay the check. At least there wasn’t wine.

After the reading students asked all the questions, always a good sign. The funny man spoke about how as an undergraduate he changed majors several times, took a studio art class and painted paintings just because he was interested. He got a lot of Bs, he admitted, and didn’t like everything, such as the enormous lecture hall classes where people read their newspapers and fell asleep. He talked about his experience earlier in the day at The Soybean Press and pointed to the opportunities a large land grant university provided, how there were hidden wonders to engage with at every turn. As a student he hadn’t ever expected to be standing there at the lectern, he said, sounding a little like his character, but he thought his own curiosity and what the school had offered as a whole had helped shape him into the person he was. Looking at the young faces in the audience, one could tell they thought he too was one of those added benefits, like the Press, and that’s no joke.

***

*The funny man is my old friend and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency editor, John Warner, whose previous books are My First Presidentiary; Fondling Your Muse: Infallible Advice from a Published Author to the Writerly Aspirant; and So You Want to Be President. He co-runs The Morning News Tournament of Books, and he is the Biblioracle. He currently teaches at College of Charleston. Buy The Funny Man here.