You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

27 January 2013

Dear [hypothetical] colleagues,

I am sure you, or some of your fellow trustees, noticed Thomas Friedman’s op-ed (‘Revolution Hits the Universities’) in this weekend’s Sunday New York Times. Friedman, author of The World is Flat, did a characteristically effective job in raising attention about a phenomenon (massive open online courses, or MOOCs) worth thinking about.

If you have not already pushed your senior leadership to respond regarding the MOOCs idea, I’m sure this op-ed will become the straw that broke the camel’s back, so to speak. The questions you might initially ask include, no doubt, are we in the MOOCs game? If so, what’s on offer, or in the pipeline? And if not, why not, or what’s the hold-up or valid counter-argument. This is, after all one of the issues that stirred up last summer’s brouhaha over governance at the University of Virginia.

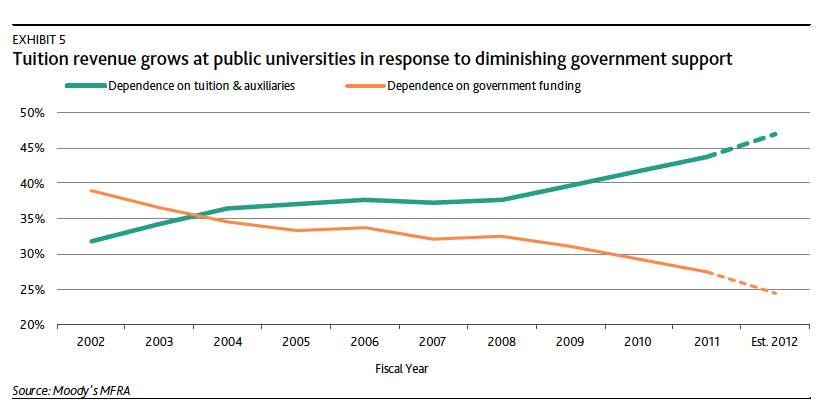

To be sure, it is an opportune time to engender a broader debate about the MOOCs phenomenon. This is an era of significant change in the nature and futures of higher ed. Moody’s, for example, downgraded the entire US higher education sector on 16 January and released a report that included this striking time-series graph:

As Moody’s also pointed in the same report, MOOCs are partially an outcome of a:

fundamental shift in strategy by industry leaders to embrace technological changes that have threatened to destabilize the residential college and university’s business model over the long run.

Thus MOOCs can be perceived of as a threat; a private authority-enabled mechanism that may lead to the unbundling and separating out of the provision of some teaching services from the faculty base at your institution, as well as many aspects of the direct and indirect credentialing process.

For those in the MOOCs game, are there at least some benefits for universities? In the same report Moody’s notes that there are, for some types of universities at least (the types Friedman praises in his op-ed), and these could include:

- New revenue opportunities through fees for certificates, courses, degrees, licensing or advertisement

- Improved operating efficiencies due to the lower cost of course delivery on a per student basis

- Heightened global brand recognition, removing geographic campus-based barriers to attracting students and faculty

- Enhanced and protected core residential campus experience for students at traditional not-for-profit and public universities

- Longer term potential to create new networks of much greater scale across the sector, allowing more colleges and universities to specialize while also reducing operating costs

- New competitive pressure on for-profit, and some not-for-profit, universities that fail to align with emerging high-reputation networks to find a viable independent niche.

There are some major caveats, though, to factor in when it comes to the Thomas Friedman/Moody’s/et al, argument; the one buzzing and humming through the system right now, propelled as it were by people, firms and organizations with vested yet often unstated interests in making you feel concerned, if not agitated.

The first caveat is that Friedman has seized upon the MOOCs platform as it serves as a defacto metaphor for his long held ‘world is flat’ argument. Friedman revels on the collapse of time and space brought on by MOOCs and notes, for example:

Yes, only a small percentage complete all the work, and even they still tend to be from the middle and upper classes of their societies, but I am convinced that within five years these platforms will reach a much broader demographic. Imagine how this might change U.S. foreign aid. For relatively little money, the U.S. could rent space in an Egyptian village, install two dozen computers and high-speed satellite Internet access, hire a local teacher as a facilitator, and invite in any Egyptian who wanted to take online courses with the best professors in the world, subtitled in Arabic.

However, as pointed out by economic geographers, and well known social scientists like Richard Florida and Saskia Sassen, we actually live in a ‘spiky world.’ This spikiness is a pattern associated with most factors of production and consumption, including internet access and the production and circulation of knowledge. Moreover, forms of knowledge do not travel in an uncontextualized nor uncontested manner; they are built upon societally-specific assumptions, depend upon years of prior learning to make sense of, and sometimes rely upon geographically- and historically-specific case studies to ensure effective transmission and learning. So yes MOOCs can jump scale, but they face the same problems most of our other technologies and knowledge transmission systems have had for decades. It is arguably ineffective to legitimize MOOCs at your university by implying they’ll help you save the (non-Western) world like Friedman does.

Second, while Friedman’s article implies a relatively easy Yes or No decision re. going ahead (we are, after all, supposed to be in the middle of a “revolution”) the direct and indirect resource base required to establish and maintain MOOCs is nothing to be sneezed at. For example, it was good to see that he profiled Mitchell Duneier’s Coursera course. What Friedman failed to note was that Princeton is an extraordinarily wealthy private university that has the capacity to provide undoubtedly brilliant and hard working Duneier with sufficient support to run his MOOC, including via designated assistants. Online teaching can scale more easily than in-person teaching, but the creation of the institutional space and support infrastructure to produce a series of quality MOOCs takes time, attention, resources, TLC, and so on. The production process also has to be preceded by the creation of a formal or informal governance pathway, as well as an assessment if your university has the technological and organizational capabilities to coordinate a legitimate MOOCs initiative.

Third, Friedman is portraying a phenomenon that is being deliberately stirred up by more than just an interest in enhancing innovation and global access via a scale jumping technology -- there is also a complicated and fast evolving political economy to MOOCs (and online education more generally). Narrowly, the phenomenon is well worth experimenting with, in my humble opinion. I would agree with Friedman that this is an amazing time to innovate and take advantage of the platforms and learning management and analytic processes engendered by the backers of platforms like Coursera, Udacity and edX. Yet if you follow the debate closely, some firms and political actors/advocates in the US have deemed online education and MOOCs, in particular, as an answer to fiscal constraints; a ‘silver bullet’ of sorts to ensure taxation levels do not budge, or indeed go down. But look again at the graph from the Moody’s report I pasted in above: this shift in financing is nothing short of a structural change that has moved beyond the notion that austerity is a response to a cyclical crisis.

We are now in a new (normalized) normal, at least in the US, where austerity is accepted and indeed viewed positively for it can be perceived as a mechanism to restructure higher education systems and institutions. In short, we are arguably (as noted by Dean Martin McQuillan in an article in Times Higher Education magazine) not in a state of ‘crisis’ as ‘crisis’ infers a cyclical dimension to the challenges facing the financing of higher ed. Austerity (the strategic and systematic reduction of state-financing levels), in combination with the contradictory/ironic desire to ramp up state governance power (including about online education and associated credentialing), is the new normal and this is what Friedman, amidst all his hype about MOOCs and online education, utterly fails to flag.

You obviously will have your own views about the validity of my argument and please feel free to disagree. But regardless of your view, let me point our that there is a real risk in the US higher education context that MOOCs will become a politicized platform: if they start to be perceived as a Trojan horse to dismantle the public university, or as a 'rope' to strangle ourselves, the 'baby' may get thrown out with the 'bathwater' and the positive features of MOOCs (and there are many!) will be lost amidst the associated conflict. In short, there are political and economic machinations associated with the stirring of interest in, and coverage of, MOOCs. Given this, and given the stakes at hand, it is important to address the MOOCs phenomenon is a serious, sustained, and reflective way, not in a knee jerk fashion, one way or the other.

My next memo will focus on the international dimensions of MOOCs, an issue also grappled with in two earlier entries in GlobalHigherEd.