You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Almost four months ago my EdX/WellesleyX course, “Was Alexander Great?” was launched to test three questions about online education: whether a Massive Open Online Course could be as intellectually rigorous as a brick and mortar history course; whether a MOOC could serve as a portal for both teaching and historical research; and whether an online course could engage and inspire students. The data are in and the answer to all three questions is an emphatic yes.

History 229X lasted 15 weeks and included 26 classes. For each of the classes there were assigned source and scholarly readings. Altogether there were 159 lecture modules that the students were required to watch and 116 forum discussion questions posted for students to respond to. Over the 15 weeks of the course the students posted thousands of responses to the forum questions. My two student assistants and I wrote hundreds of responses to the students every week.

The course also included 2 Surveys about Historical Leadership and Alexander, 21 multiple choice, factual quizzes, 4 map quizzes, 1 voluntary art historical exercise, 1 mid-term exam, 1 voluntary source critical writing assignment, a voluntary “Eulogy of Alexander” writing assignment, and 1 comprehensive final exam. I have never taught a course at Wellesley College (or anywhere else) that included so many exams and exercises that tested both knowledge of content and skills of so many different kinds.

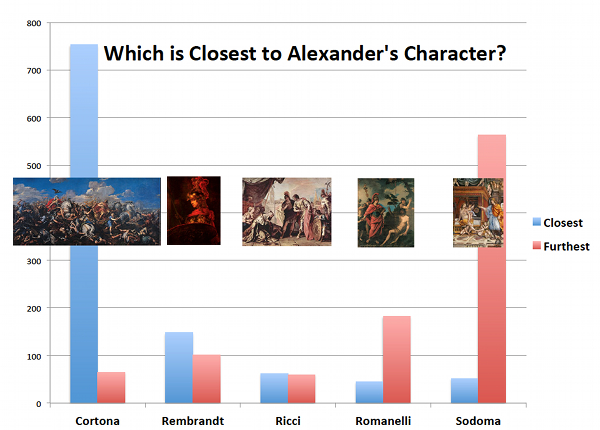

Over 1100 students chose to take part in our art historical exercise. The exercise involved choosing one painting from a group of five famous paintings of Alexander (by Cortona, Rembrandt, Ricci, Romanelli, and Sodoma), and then posting reasons why students thought the painting they chose came the closest to exemplifying “The Real Image of Alexander.” We then posted a graph that showed which paintings came the closest to or furthest from representing Alexander’s character according to the students’ votes.

At the same time, more than 850 students took our multiple-choice mid-term exam and an amazing 84% of the students passed it, most of them with flying colors.

For the source criticism writing assignment I asked students to write short essays on what the ancient sources report about what or who killed Alexander the Great. The class was also given the same set of instructions for how to go about writing a source critique that I give to my Wellesley classes. Over 170 students chose to write essays that would be critiqued by the whole class online. Many students wrote essays of 5 or more pages. I wrote online critiques of all the essays that were submitted. The class then voted for the three essays that best fulfilled the assignment, given the assessment criteria I had posted. I then posed a follow up question about Alexander’s death that the authors of the top three source critiques wrote short essays about; the class then voted on the best follow up essay from among the three.

Learning how to do source criticism is a crucial intellectual skill for all students of history and is taught in virtually all brick and mortar history courses. Our exercise suggests that this skill can be taught online using a combination of peer reviews, crowd sourcing, and qualitative assessments by professors.

An astonishing 1162 students took the final exam for the course, with 862 scoring 90% or higher on it. Some critics of MOOCs have pointed to the fact that only a small percentage of those who register for MOOCs routinely “finish” classes. Students in MOOCs can engage in such courses in a variety of ways, but it is true that about 6% of the students who registered for my class completed the final exam. But the total of 1162 students taking the final exam in this one course is more students than I have taught at Wellesley College over the past ten years. Even more incredibly 554 got perfect scores on the final. Overall, 1039 earned a passing grade in the course and received a certificate. Out of those, 760 finished with 90 points or above on all the exams and exercises and thus became members of our course Honor Roll.

History 229X also suggests that MOOCs can yield historically significant research. Throughout the course students contributed to our course glossary, our research bibliography, and our image archive. After the close of the course these research sites have been archived for future use.

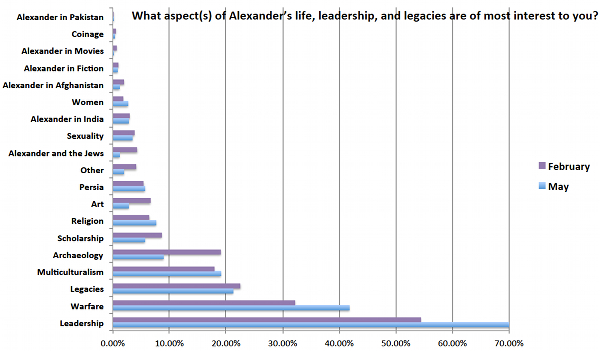

At the end of the course we once again surveyed our students about their attitudes toward Historical Leadership and Alexander. When we surveyed the students at the beginning of the course our students selected intelligence (17%), the ability to persuade others (13%), and vision (11%) as the three most important characteristics of an effective leader, and 64% of them thought that leadership was both genetic and could be taught. After taking our course an even greater percentage of students concluded that leadership is both genetic and can be taught, that courage and intelligence were essential characteristics of effective leaders, and that Alexander’s self-sacrifice and flexibility were characteristics that made him such an effective leader. (Please see the survey below.) These results represent a contribution to the study both of historical leadership and Alexander.

Inspiring engagement, passion, and a love of learning are of course harder outcomes to measure. At the end of our course however we asked the students to fill out course Evaluation Surveys and a very high percentage of the students highly recommended both the course and the instructor. Without any prompting from EdX or WellesleyX students also decided to form ongoing Alexander study groups, requested more history courses like the Alexander course, and asked if we could organize a study tour overseas to follow in the footsteps of Alexander the Great. We also received many unsolicited letters from students telling us how much our course had inspired them.

At the beginning of each course I teach at Wellesley College I tell my students that a Wellesley College education is an education for a life-time and the value of what they have learned at Wellesley may take years or even decades to appreciate. That is one of the primary benefits of a liberal arts education. If professors and those who assist them in creating MOOCs such as History229X are willing to engage students of online courses with passion and commitment, then MOOCs not only can teach students many of the historical skills that are learned in traditional classrooms. MOOCs can inspire students all over the world and change their lives too.

Guy MacLean Rogers is Kemper Professor of Classics and History at Wellesley College.