You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Anyone who has experienced long supermarket lines and empty Home Depot shelves where snow blowers once sat has witnessed the classic case of a sudden increase in demand creating a shortage in supply.

In higher education, there are demand drivers for different degrees and credentials: employers may need a workforce with new skills, a new regulation might be put in place, a shift in demographics may create a need, etc. -- and institutions can choose to respond accordingly.

Take the nursing profession, for example. It’s no secret that demand has increased, and nursing schools have responded.

.png)

Source: American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Research & Data Center, 1994-2011

However, according to the data released last week by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), 75,587 qualified applicants were turned away from nursing schools last year. This is not something new to education -- or nursing -- and it’s not necessarily the schools’ fault.

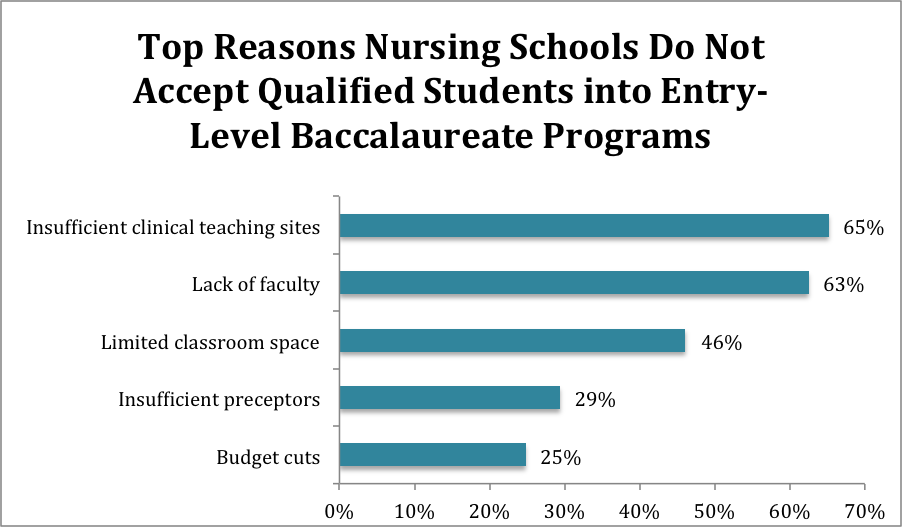

Shown in the graph below, the top reasons nursing schools could not accept all qualified students include insufficient teaching sites, lack of faculty, limited classroom space, insufficient preceptors and budget cuts. These are real challenges.

Source: American Association of Colleges of Nursing

Sometimes these are insurmountable, other times schools can get creative.

For example in veterinary medicine, according to Veterinary Information Network, “Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, CA., has the only accredited veterinary medical program in the United States that’s successfully bypassed the teaching hospital condition. Rather than having its students rotating through an on-campus hospital, Western U has adopted a “distributive model,” which involves a partnership between the university and 300 or so private practices. It’s in those private practices that third- and four-year students are expected to learn their clinical competencies.”

Then there’s the “2+2 arrangement,” in which new veterinary schools partner with existing schools that have teaching hospitals. Students start at the new school and finish their final two clinical years at the existing school.

Schools may find it easier to respond to trends outside the medical field. Here are just a few new degrees that have been announced recently.

- Alabama State University just announced a new master’s degree in applied technology.

- Husson University will offer four new undergraduate degrees: forensic science, software development, environmental science, and hospitality and tourism management.

- Fordham’s Graduate School of Business will introduce three master’s degrees this fall: marketing intelligence, business analytics and media entrepreneurship.

- Michigan State University is offering a new Doctor of Educational Leadership degree.

Finally, they say that what goes up must come down. It becomes more about timing. If a school expands late there’s a chance the demand may wane, or already be met by other schools. Sometimes anticipating and/or responding to those downward trends can be just as important. For example, according to Friday’s Chicago Tribune, law schools are experiencing a second year of application “double-digit percentage declines.” A sign of more declines to come? Too soon to tell.

One thing is certain - even a new degree or school created based on the most careful, accurate mapping of external trends with internal capabilities may fall short if the timing is off.

What do you think the next degree ‘bubble’ will be?