You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Franklin University

Name of Institution: Franklin University, in Columbus, Ohio

The Problem: Most of Franklin's 5,000 students come to the university with some community college credits, but many of the mainly adult learners were struggling in the more challenging English and math gateway classes, said Karen Miner-Romanoff, associate provost for academic quality.

“We feel a great obligation to the student narrative,” she said. “Our adult students expect that from us. They especially want universities to be more accountable.”

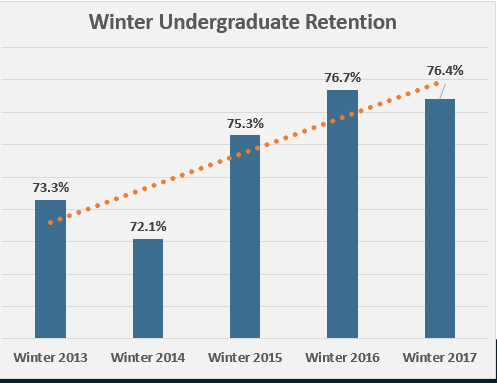

By the winter 2014 trimester, Franklin's undergraduate term-to-term retention rate had fallen to its lowest point, 72.1 percent, since the institution began collecting the data in 2008, according to Blake Renner, associate dean of students. Renner said Franklin defines term-to-term retention as students at any level who took classes one trimester and then registered for classes the next trimester.

The Goal: Build a data-based model to support student success in challenging gateway courses, utilizing all relevant data aggregated from across the institution to develop evidence-based interventions. Besides boosting success and retention of undergraduate students (85 percent of students take all classes online), Franklin also wanted to help its graduate students, especially those in Ph.D. programs. Minor-Romanoff said that 50 percent of doctoral students, in general, don’t graduate because they don’t finish their dissertation. “Our goal is 100 percent,” she said.

The Experiment: Franklin began an initiative to systemically improve its data collection and to add new sources of data, such as student and instructor reflections, to its course evaluations.

Minor-Romanoff said Franklin’s centralized curriculum development allowed for experimentation with data-driven design and teaching initiatives. She said the first goal was to assess what data were available, what information was relevant for student success and retention, and what models of analysis could direct decisions. The next step was to provide faculty course designers and content experts with the necessary information to develop courses that would lead to greater student success.

Franklin reviewed its most challenging gateway courses as defined by student enrollment and failure rates, and chose 24 to analyze with a variety of data, including students' stated reasons for withdrawal, grade distribution, course design, faculty and tutoring surveys, library support and instructor observations.

Then the university began building coalitions across campus to learn what qualitative and quantitative data needed to be collected. Minor-Romanoff said the formation of coalitions was important because, for instance, librarians collect student feedback on course assignments that use library services, and tutoring surveys provided information about where students were seeking additional course support.

While improving data aggregation, Franklin simultaneously developed new processes to analyze data to better allocate resources. Minor-Romanoff said the effort led to improvements in course evaluations, faculty observations and learning management system (LMS) analytics.

Several dashboards and data management systems work separately while Franklin staff members aggregate the data, manually in many cases, using homegrown technology, she said.

What Worked (and Why): The efforts helped boost undergraduate student retention from 72.1 percent in winter 2014 to 76.4 percent in winter 2017, Renner said. He added he expects that the winter 2017 percentage will match or better last winter's 76.7 percent retention rate when this trimester ends.

Although the percentage rise looks small, Renner said it translates into "hundreds and hundreds of students retained."

The initiative also led to increased focus on how to utilize data in a systemic, holistic way, Minor-Romanoff said. "In many ways, the university data and communication silos diminished because faculty, staff and administrators are sharing in the university’s efforts," she said.

New forums are providing other recommendations. For example, several faculty members recommended broadening data collection to show students’ academic pathways, the provost said.

What Didn’t Work (and Why): Some designers and instructors were reluctant use the data due to concerns about validity. Now Franklin is combining qualitative data, such as peer-teaching observations, with quantitative data, such as student assessment of learning outcomes, in hopes of “managing the difficulty of change,” Minor-Romanoff said.

And not every one of the 24 gateway courses experienced increased student retention. Minor-Romanoff said that instruction and student support, which are critical in gateway courses, may have significantly influenced the retention rates in specific courses.

Next Steps: Franklin soon will make data available in real time to students and instructors. Minor-Romanoff said that research indicates that students’ success and retention improves when they have access to personal data, and when instructors have data that pinpoints which learners need extra support and what type of support they need.

Working with faculty members, Franklin also is creating a universal outcome mapping project to allow assignments to be mapped with students’ learning outcomes so learners can see their progress.