You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Faculty members at the University of Maryland University College – whose president, Susan C. Aldridge, was placed on indefinite administrative leave last week – have repeatedly expressed dissatisfaction with the university’s administration, raising concerns about pay, shared governance, and professors' views that the administration lacked interest in academic standards.

When they received no response from the university's administration, based in Adelphi, Md., they took their concerns to the University System of Maryland, which oversees the institution and 11 other public universities in Maryland. In November 2010, faculty members in the university’s Asian division, which serves students in Japan, Korea, and Guam, sent a letter to William E. (Brit) Kirwan, the system’s chancellor, highlighting the findings of a survey they conducted among themselves.

“The attached faculty survey is a de facto vote of no confidence in the present administration,” wrote Mervin B. Whealy, a former member of the Faculty Advisory Council representing the Asian division, who wrote the cover letter to the survey. “Issues that have degraded faculty morale in Asia include the declining economic value of UMUC employment, a lack of shared governance, problems associated with the appointment of the next Asian Director, the Aldridge administration’s insufficient interest in academics, and the management of the Asian division and Adelphi.”

The University System of Maryland has not yet offered an explanation for why Aldridge was placed on leave. UMUC faculty members do not have tenure, so those asked to comment declined to speak on the record or be quoted. Several said they do not think faculty complaints were the reason Aldridge was placed on leave, since the complaints have been on the books for a while and the system has shown no hint of action until last week.

UMUC is one of the largest public universities, serving more than 90,000 students in the U.S., Europe, and Asia, including many active military personnel. It has grown significantly in the past two decades. In 2000, the university reported that it enrolled 71,560 students. In 2011, it reported that it enrolled 96,342. Many of these students are part-time, so the full-time equivalent enrollment is about 32,000.

UMUC has often been held up as a model of how public higher education can take advantage of tools often employed by for-profit institutions – such as online education and sped-up course schedules – to reach a group of nontraditional students that four-year, residential campuses rarely do. The survey from Asia and other complaints from faculty members in the United States show that the university’s notable gains haven’t been made without some resistance from faculty members and that problems have existed beneath the surface for several years.

A spokesman for the University System of Maryland said there has been no public airing of the issues raised by the survey, and that any concern about the manner in which an employee has conducted his or her duties is a personnel matter and therefore confidential.

The survey was sent to 104 faculty members in the Asian division, and 53 of those faculty members responded -- a fraction of the university’s total of about 2,200 faculty members. The overwhelming majority of UMUC faculty members work for the institution part-time.

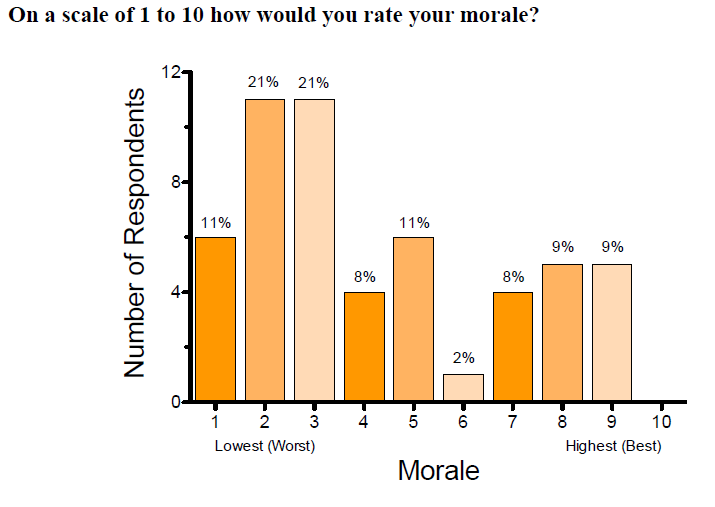

Rating their morale on a scale from one to 10, with 10 being the highest morale, more than half of the survey respondents said their morale was a three or lower.

The issues that most faculty members said contributed to low morale were tied to compensation, including a lack of raises in the previous three years; the currency-adjustment formula; and their housing allowance.

“Morale is low in the Asian division because the administration seems to have little regard for our economic condition and basically gives us the choice of ‘quitting’ if we do not like these conditions,” one survey respondent wrote. “We need some encouraging word about their intentions regarding our economic condition in the future.”

Many respondents also said administrative turnover, academic issues, and a lack of shared governance were factors in the low morale. “At UMUC, shared governance has little practical meaning,” Whealy wrote in the letter. “When the Asian faculty sent a letter to Dr. Aldridge in 2010, expressing concerns about its degraded financial condition, she did not respond.”

Responses to open-ended questions throughout the survey decried the university’s top-down leadership style. Respondents said the administration was not open to input from faculty members, even on questions of academics, where faculty members at most traditional colleges and universities tend to exert significant authority. They also complained about the departure of several administrators whom faculty respected.

“The mysterious firings and resignations of competent [administrators] tell us that the integrity and high standards of our university are not a priority in Adelphi,” one respondent wrote, referring to the university's headquarters. “When our best advocates leave, and cannot tell us why – something is very wrong. It harms morale and increases distrust of administrative policies.”

Faculty members outside the Asian division have also complained about the university’s rapid embrace of technology and course restructuring over the last five years, which have placed an increased workload on them while, in their opinion, diminishing the quality of the education offered, faculty members said.

The university has moved quickly to reformat classes to make better use of online technologies and to transform the schedule. Classes have been pared down from 14 weeks to eight weeks to make offerings more flexible, particularly to accommodate military personnel who often don’t have a full 14 weeks to take a class.