You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

American Institutes for Research

Lot of research says that having kids puts women at a disadvantage on the academic job market, especially in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields. But a new study suggests that kids are equally, and in some cases more, hazardous to men’s academic career prospects.

“Pathways in STEM: Do Gender and Family Status Matter?” is based on survey data tracking the first jobs of math and science Ph.D.s upon graduation. The report, out today from the American Institutes for Research, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, finds that the rate of employment of men in any kind of job – within academe or outside – upon finishing a math or science Ph.D. is 70 percent, compared to 65 percent for women.

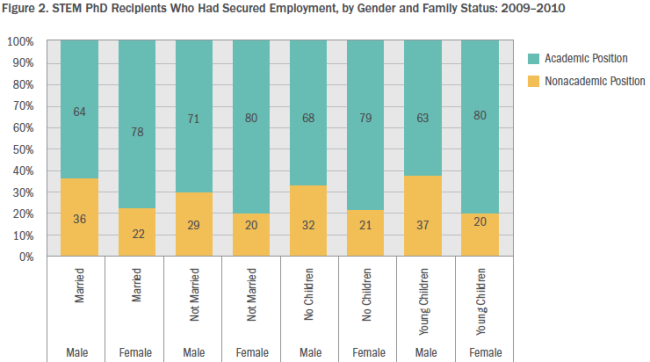

Of those employed, women are much likelier to take jobs in academe, (79 percent vs. 67 percent, respectively), defined as tenure-track and postdoctoral positions, than in non-academic fields, such as government and the corporate world. Married men and men with young children were the least likely of all recent Ph.D.s to begin their careers in academe, at 64 percent and 63 percent respectively. That’s compared to 78 percent for married women and 80 percent for women with young children.

But men still land first jobs at a higher rate at research universities (13 percent, compared to 10 percent of women), which are considered the “most prestigious” kinds of positions, the report says. Married recipients with STEM doctorates are significantly less likely to begin their academic careers at a research institution, regardless of gender. And both men and women with children are even less likely to secure first jobs at research universities than their childless, married cohorts.

“These results seem to affirm (but also complicate) prior scholarship suggesting that women, over all, may be getting pushed out or may be pulling out of research-intensive and more prestigious pathways early in their careers,” the report says.

It continues: “Institutions of higher education have a critical opportunity to capitalize on women’s early career interest in STEM academic positions, but only if they and their STEM departments are willing and able to create cultures and infrastructures that are welcoming to women and that can promote their successful transition into and retention in rewarding academic careers, even within the most research-intensive environments.”

“Pathways in STEM” is based on 2009 and 2010 data from National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates. The authors considered data from 27,724 respondents, all of whom had secured jobs upon graduation.

Courtney Tanenbaum, co-author, said in an interview that, as is made clear in the report, women who want academic STEM careers still face challenges. She noted that the report deals only with women who have finished their degrees, and doesn’t take into consideration women who have left programs due to family status or biases.

But the data show that men with children take on academic positions at lower rates than their peer groups, Tanenbaum said. So institutions that are serious about supporting faculty members with children need to rethink the traditional professor career arc, which is unforgiving to those who take time off and seek greater work-life balance.

“Men are taking care of children and playing a bigger role at home and if we don’t change these policies and practices, men, too, are going to be pushed into other types of career choices,” she said.

Nicholas Wolfinger, an associate professor of family and consumer studies at the University of Utah, co-authored the book Do Babies Matter?, part of a well-known long-term project of the same name on gender and family status in academe. Researchers involved in that project have found that the academic pipeline is leakier for women – and women with children in particular -- than for men early in their careers, especially in STEM. Wolfinger said that the new report was “unconvincing,” in part because the data “misses everyone who finishes graduate school before seeking employment.” Do Babies Matter is based on a more comprehensive data set, including the Survey of Doctorate Recipients, which tracks Ph.D.s throughout their careers. "Pathways to STEM" is a "snapshot" rather than a complete picture, he said.

The new report acknowledges Wolfinger's and his colleagues' work, but says it wanted to explore gender and family status among STEM Ph.D.s "at the onset of their careers." Tanenbaum said it's meant to add to existing research on the topic, and that it raises questions for further study. For example, she said, what kinds of “biases” are motivating these early career choices?

“Are women not being offered jobs [at research institutions] or are they opting themselves out? ...That qualitative data, we don’t have that.”