You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Michael L. Weinman

A former staffer at the University of Tennessee at Martin says she was fired after she voiced her support online for cleaning a filthy microwave oven, but her case against the institution will likely have more to do with the free speech rights and responsibilities of administrative employees than with dirty dishes.

The microwave in question was housed near the information technology security department’s help desk, where plaintiff Angela J. Fortner served as IT manager and supervisor of about 17 full- and part-time employees until her termination last October.

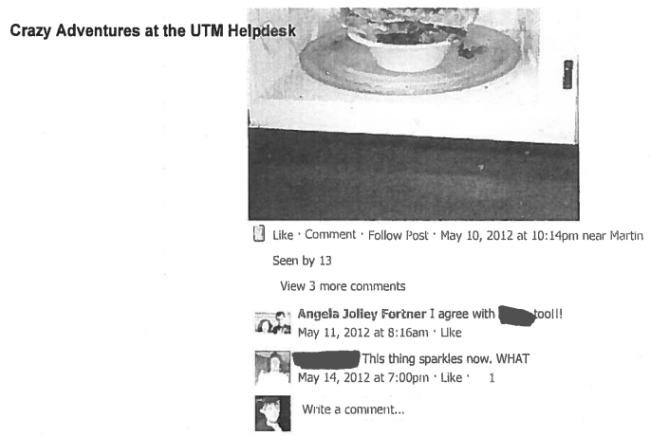

Nineteen months prior to that, in March 2012, Fortner was invited to join the private Facebook group “Crazy Adventures at the UTM Helpdesk,” created by a former student employee. On May 10, another member of that group posted a picture of and criticized a mess that had been left in the microwave, which drew comments from several members, including Fortner.

“I agree with [the original poster] too!!!” Fortner wrote the next day.

The engagement apparently led to action. On May 14, another member posted “This thing sparkles now. WHAT.”

A screenshot of those posts was provided to Inside Higher Ed by Fortner’s attorney, Michael L. Weinman. Dated Oct. 12, 2013, the screenshot suggests the group existed for more than a year before the university responded to it.

Fortner, described in the complaint as “an exemplary employee [who] had never been subjected to any disciplinary actions as an employee,” was on Oct. 11, 2013, asked to meet with J. Phillip Bright, director of human resources, and her supervisor, Terry Lewis, to “discuss issues involving her employment.”

“Lewis stated that because [Fortner] had joined the Facebook group, viewed some of the information on the group’s page, and did not ‘do’ anything about the group that she had two options: resign or be terminated,” the complaint reads. “Lewis and Bright then produced a resignation form that had already been prepared and ready prior to the meeting.”

According to the complaint, Fortner says her participation in the Facebook group was constitutionally protected speech, and that the institution’s handling of her termination violated both university policy and the due process clause of the 14th Amendment.

The group contained more than just banter about the state of the help desk’s appliances, however. In a May 7, 2012, post, one of the group’s members -- not Fortner, based on the profile picture -- poked fun at a person at the university for contacting the help desk.

“Got a call today from a lady who states having to put in 4 pieces of information to change her password is a nightmare,” the post reads. “[W]onder whats it [sic] like when she has a dream about killer zombie clowns......”

While faculty members, protected by academic freedom, are often free to gripe about their frustrations, those in non-faculty roles are at many institutions subject to the kinds of limits on public speech seen in the corporate world. Last year, for example, a University of Pennsylvania admissions officer was fired after quoting snippets from college application essays on her Facebook page.

Personal social media use -- and how, or if, to regulate it -- continues to be a tricky legal area for colleges and universities. The Kansas Board of Regents last fall reacted to one faculty member’s tweet linking the NRA to a shooting massacre with a new set of social media guidelines, which the American Association of University Professors slammed as “severely overbroad.”

Many institutions, including those in the Tennessee system, have avoided regulating social media specifically, choosing instead to include it in a broader IT policy. The policy allows students and visitors to access the the network for personal use, but in general “The university's IT resources are provided for use in conducting authorized university business.” The language is echoed in Tennessee’s general code of conduct, which also specifies that university resources should only be used for “legitimate business purposes.”

It is also the policy endorsed by the National Association of College and University Attorneys, which does not have a collection of social media best practices.

“I don’t have policies that are specific to specific media, because from a legal standpoint, the medium is not the message,” said Steven J. McDonald, a former NACUA board member who serves as general counsel at the Rhode Island School of Design. “It may be helpful to inform people that the same rules apply everywhere else apply here. For some reason, a lot of people’s brains turn off when they hit the button on their computer. Having a policy for social media and breaking it down even more -- a Facebook policy, a LinkedIn policy -- the sack of policies gets awfully big, and if nobody read the first one, it’s not likely they will have read the 14th through the 74th.”

Bud Grimes, a spokesman for the university, declined to comment, citing “ongoing litigation involving a personnel matter.” The case is awaiting scheduling in a Tennessee district court.