You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

UCSD

Academic advisers at the University of California at San Diego will this fall be able to tell on a scale from zero to 10 if the student sitting in front of them is on track to graduate within four years.

The university is in the process of rolling out its Time to Degree Early Warning System, which uses predictive models to determine if students are in danger of taking longer than four years to graduate. By combining historical data with data gathered from students as they progress in their studies, the university says, the system could one day be able to automatically suggest helpful programs and services to students who show signs of veering from the path that led former students to graduate on time.

At launch, the system will be fairly rudimentary, looking only at data such as grade point averages and units completed. But as it grows to include different kinds of data, the university hopes to one day offer what it describes as “the academic equivalent of preventive medicine.”

“We want to be able to identify students who are doing fine but are probably going to have troubles later on,” said Douglas P. Easterly, dean of academic advising at UCSD's John Muir College. “Our hope is -- and this may sound paradoxical -- by automating a lot of the screening, we can move students toward more personalized one-on-one attention.”

Many universities use an early warning system -- in many cases a commercial system. UCSD is building its own system from scratch, which Easterly said gives the university more freedom. The university can add new data sources, control how students’ data are used and repurpose the system for new tasks. While at launch the system will be used to boost the university’s overall four-year graduation rate -- a major priority in the state -- future iterations could look at specific courses, majors and students, he said.

Data from the federal government show UCSD's four-year graduation rate for students who entered in fall 2008 sat at 57 percent, lower than several other universities in the system.

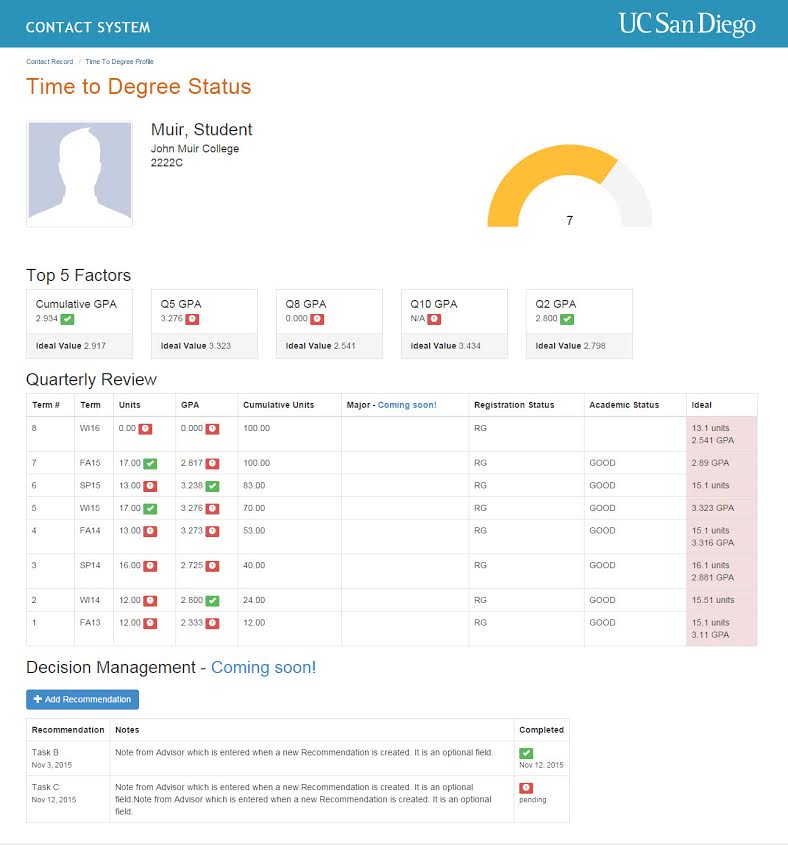

In its current form, the system presents data about a student’s likeliness to graduate within four years in a dashboard. It gives advisers a confidence rating -- a number on a scale from zero to 10 -- as well as the factors influencing that score. The dashboard shows information such as cumulative and quarterly GPA, academic and registration status, and -- importantly -- how those factors compare to what the system knows about past students. If a student is falling behind the “ideal” pace set by someone who graduated in four years, the dashboard flags it for the adviser.

At John Muir College, which has a student-to-adviser ratio of about 600 to one, that type of automated advising could free up time for advisers to spend on the students who need it the most, Easterly said. A student with a high confidence rating may only need a quick 10-minute degree audit, while a student not meeting the benchmarks may need more time to discuss how to avoid missing his or her intended graduation date.

A handful of advisers are testing the system this spring. A wider launch is planned for this fall.

Targeting the 'Murky Middle'

Research from the Education Advisory Board, a Washington-based research and consulting firm, has suggested that colleges can maximize their graduation rates by targeting students doing fine but not great. The EAB calls that segment of the student population, defined as students who end their first year with a GPA between 2.0 and 3.0, the “murky middle.”

Ed Venit, a senior director at the EAB, said UCSD is about to encounter the same questions facing members of its Student Success Collaborative, a group of dozens of colleges and universities working together to improve student persistence and retention.

“UCSD is at the beginning of a journey,” Venit said. After the system launches and the focus shifts to connecting students with low confidence ratings to relevant support services, he said, the university will need to ask itself, “What’s the infrastructure needed to build that out?”

UCSD is already planning for the next stages of the system’s development. While the dashboard is only viewable by advisers at the moment, students could possibly gain access to it in the future. The more substantial changes to the system, however, will come from the university vetting and adding new sources of data, Easterly said.

At the moment, the university is pulling the data influencing the confidence rating from the student information system, but Easterly said there are many other potential sources. “We’re awash in student data,” he said.

That presents two main challenges, Easterly said. First, the university has to make sure the data it adds to the system are statistically significant when it comes to determining if students will graduate within four years. Second, the university has to decide where to draw the line between what is useful and what is an invasion of privacy.

“We’re taking time to figure out how to do that without closing doors,” Easterly said. Mainly, he said, the university wants to avoid a situation where an adviser looks at the dashboard and tells a student, “You have low incoming test scores and you’re a low-income Latino -- maybe you shouldn’t be an engineering major?”

Easterly said one long-term goal for the system is to make it adapt to students depending on where they are in their academic careers. Using standardized test scores to inform the advising process likely yields valuable information for freshmen, but for upperclassmen, using grades they earned in college probably makes more sense, he said. Including information about parental income may make some uncomfortable -- household income quintiles could be an alternative.

“The ethical concerns of privacy are always part of the discussion,” Easterly said. “We try not to touch anything unless we have a real reason to suspect it’s useful.”