You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Senator Michael Bennet

Jennifer Buckles, the director of financial aid at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, has seen about 2 percent of federal student aid applications filed this academic year by returning and incoming students at the campus flagged for changes in income data already filed with the federal government.

It’s a small number, but with more than 14,000 copies of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid filed by the university's students so far, that means several hundred financial aid flags that her department must sort through. And with many returning students having yet to file an updated financial aid application, Buckles's office could be staring down even more of those flags.

"Each one requires us to figure out if we need to resolve it. Each one is going to take some time," Buckles said.

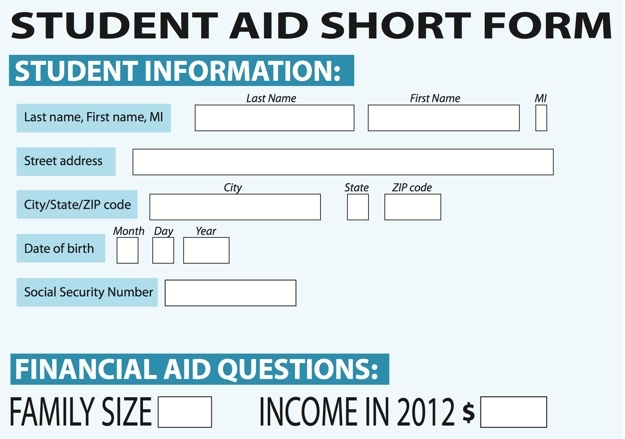

It's a problem affecting financial aid offices at campuses across the country to varying degrees. And it arises out of an attempt by the Department of Education to significantly streamline and accelerate the financial aid process for students this year. The department moved up the release date of the FAFSA application by three months to Oct. 1. And it introduced a long-discussed policy to have students use two-year-old tax information -- the most recently filed by their families with the IRS -- for income data on the application. The idea behind "prior-prior year" was that most households don't file their taxes until close to Tax Day in April, and the families of most students who qualify for aid don't gain so much income or wealth in a year that they would lose eligibility. If those students could also get notification of aid awards earlier, the thinking went, they would be more likely to enroll in college.

The new flag creating the additional work at many campuses -- known as Code 399 among financial aid administrators -- pops up when there is a change in the income data previously filed by a student's family with the federal government, possibly as a result of something like an amended tax return. The college or university must determine if the flag is valid and, if necessary, adjust the amount of a student's financial aid award based on the updated income information.

Justin Draeger, president and CEO of the National Association of Student Financial Aid Advisors, said the problem wasn't unexpected and it shouldn't continue beyond the current financial aid cycle. But that doesn't mean it hasn't become burdensome for many financial aid administrators this year.

"For some schools, it seems to be overwhelming," he said. "For other schools, we're hearing it's a pain, it's a nuisance, but they're able to work through it."

It's likely to be particularly troublesome for colleges and universities serving a high number of low-income students eligible for Pell Grants.

"This is a recurring theme in higher ed where sometimes the schools serving the highest-need students are also the least-resourced schools and struggle to keep up with these kinds of changes," Draeger said.

Gregg Scoresby, CEO of financial aid software firm CampusLogic, said the Code 399 was an example of unintended consequences of a policy switch that can become very material to many students. The company works with campuses like the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga to provide automated and mobile financial aid application products.

"The job that the school performs on behalf of the Department of Education is really an underwriting function. They don't call it that, but they are determining eligibility," Scoresby said. "And there are hundreds of these codes that a school is responsible for."

Where a legitimate discrepancy is identified by a financial aid office, a student could lose access to federal student aid they expected to receive this year, such as funds from Pell Grants or student loans. At Chattanooga, Buckles said, the typical loss of Pell awards is about $2,000.

"These are not students who have $2,000 that they can just come up with," she said.

The university is trying to make up the difference by locating institutional funds to cover that gap, but Buckles said it can't necessarily compensate every student affected. She said the campus has seen a decrease in the total number of verification checks that can slow down student financial aid applications and even deter some students from completing the process. But the income discrepancy issue has primarily affected returning students, many of whom likely won't file their FAFSA until January, as they have done in previous years.

"Returners aren't even thinking about next year. They're in 'now' mode," she said.