You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Tired of students asking for a grade change for no particular reason -- other than a non-A might ruin their holiday? Clemson University’s English department has an idea.

Rather, it has a template.

“Dear All (especially lecturers),” begins an email circulated by Jonathan Beecher Field, associate professor of English, during his stint as director of undergraduate studies. “As the semester winds down, it’s as good a time as any to remind you that the department supports you and your grading decisions. Grading writing is inherently subjective. Subjective is not the same thing as unfair. You teach in the Clemson English department because we trust your judgment. Assigning a grade is the end of teaching a class, not the beginning of a negotiation.”

As these “conversations go back and forth,” Field added, “they become less productive and more volatile. As a way of ending such conversations, feel free to respond to any and all undergraduate grade complaints with an email like this.”

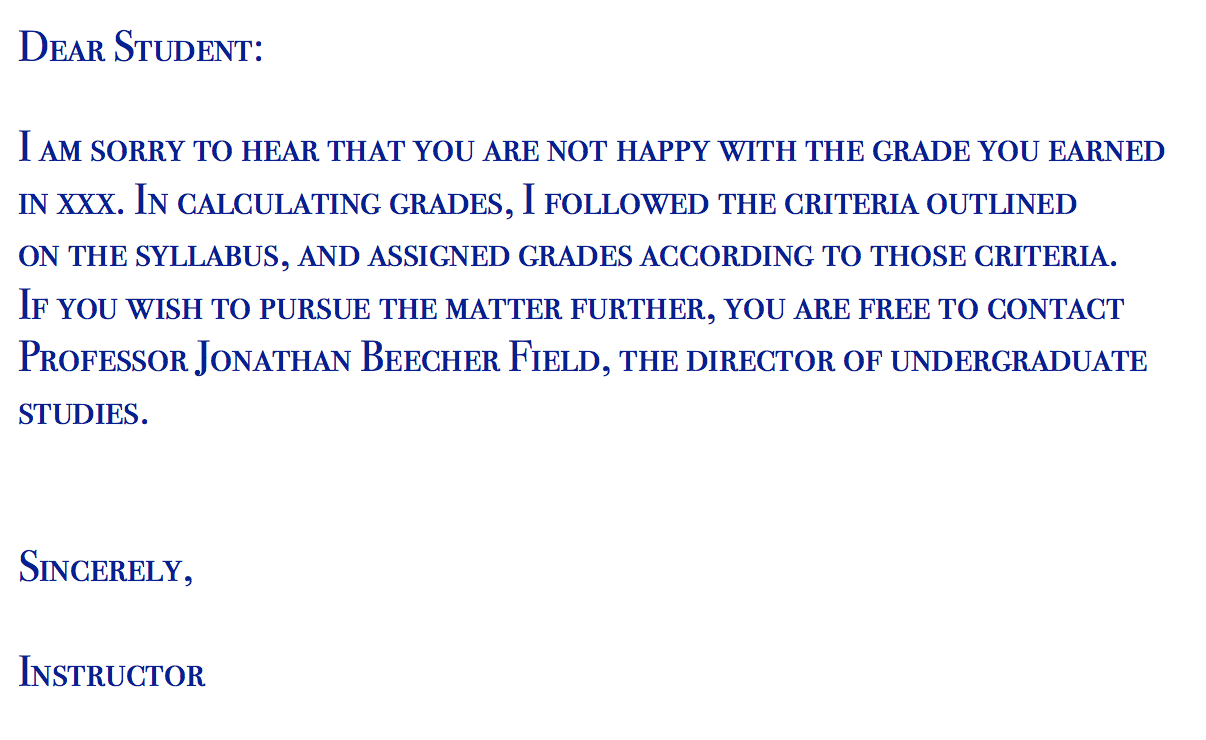

Field included the following template for instructors to use with students asking for or demanding a final grade change.

Field’s tradition has been continued by the department’s current director of undergraduate studies, Walt Hunter, assistant professor of English, who sends out a nearly identical email (his template says students also may contact the associate chair).

Horror stories about students demanding better grades certainly exist, but neither Field nor Hunter had any to share this week (both said they were relatively rare).

Instead, Field said he was more inspired to write his original email by empathy for non-tenure-track professors. Across academe, these professors’ future course assignments are most reliant on positive student feedback (a major criticism of standard student evaluations of teaching). So they’re therefore more vulnerable to student complaints about grades. They’re also more likely to feel like they don't have departmental support.

As director of undergraduate studies, Field said he shared the message with his colleagues near the end of the semester “to let them know the department supported them.” Rather than have an unhappy student “go back and forth with an instructor, the instructor can refer them to someone else in the department. If the student is still unhappy, they can talk to the associate chair, and then chair and so on.”

Field didn’t recall a complaint going beyond the associate chair. But the idea, he said, “is to have a structure where the student can express their frustration without beating up an instructor.”

Hunter said the note makes clear to “faculty of all ranks that the department supports them in their daily work in the classroom.” A few students “inevitably” can be “unhappy or frustrated with their final semester grades and ask for further explanation. Usually this amounts to a small handful of cases each year. I always offer to meet with the students and listen to them.”

Chris Blattman, Ramalee E. Pearson Professor of Global Conflict Studies at the University of Chicago, has policy-like statements about his approach to Ph.D. advising and whether or not he’ll write you a letter of recommendation and more on his impeccably organized website. But he said Wednesday that he’d never received guidance from any department he’s taught in on handling regrade requests.

Calling Clemson English’s approach “interesting,” Blattman said, “It sounds to me like they are encouraging a conversation to happen, but recognize that sometimes that conversation has to end with the instructor simply saying that they followed common criteria for the entire class.”

Does Blattman entertain grade changes? He said he and most people he knows generally do. But short of a grading error, he said, most regrade requests are “really chances to clarify the grade in terms of the student's relative performance.”

Blattman added via email, “Implicitly the question is usually ‘Why didn’t I get an A?’ and then I provide more context and detail. This might be because my grading rubric wasn’t transparent enough. But seldom do I receive a well thought out regrading request.”

Jennifer Diascro, associate academic director at the University of California’s Washington Program, said she has required students who want her to change their grades to demonstrate their knowledge of the material and how they think they have been misjudged. It’s an exercise in making compelling arguments, she said, and a bit of a sincerity test, as it “takes time and energy.”

Unless she’s made an “obvious mistake in grading something, I’m not inclined to change it,” however, she said. “Evaluating work, especially written work, is often subjective and it’s simply not fair to other students who are equally subject to my subjectivity to change grades for single students.”

Diascro mused as to whether certain kind of institutions see more requests, namely private versus public. In her own experience, she’s had “loads” of grade requests in certain jobs and few to none in others.

That said, Diascro added that she’s “pleasantly surprised” at how receptive students are to her arguments about fairness, and that most just seem to want to make sure they’re being treated fairly.