You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

Women are more likely than men to leave full-time careers in the sciences, technology, engineering and math when they become parents. But this is not just a “mothers’ problem” -- dads are leaving, too, at too high a rate, says a new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

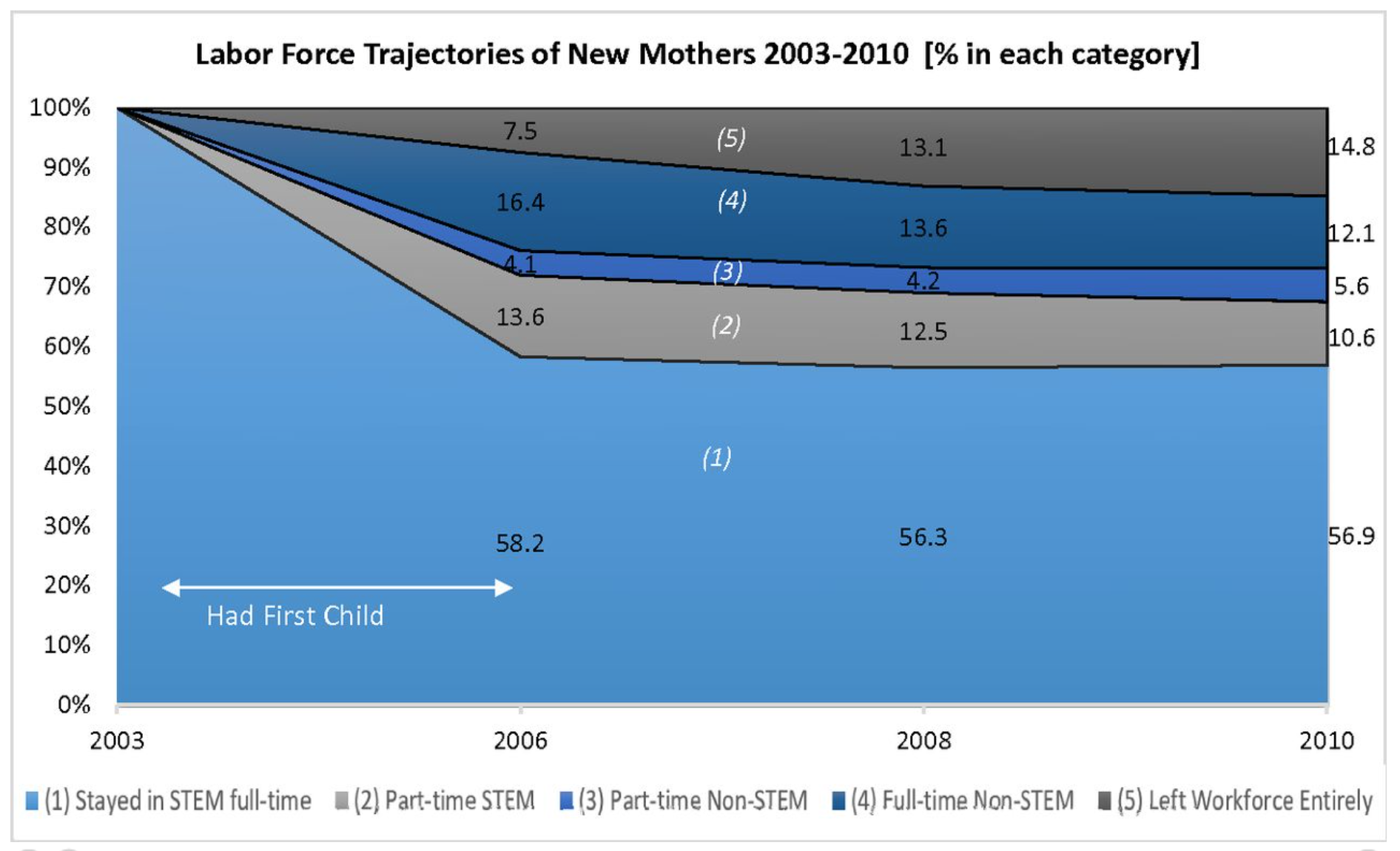

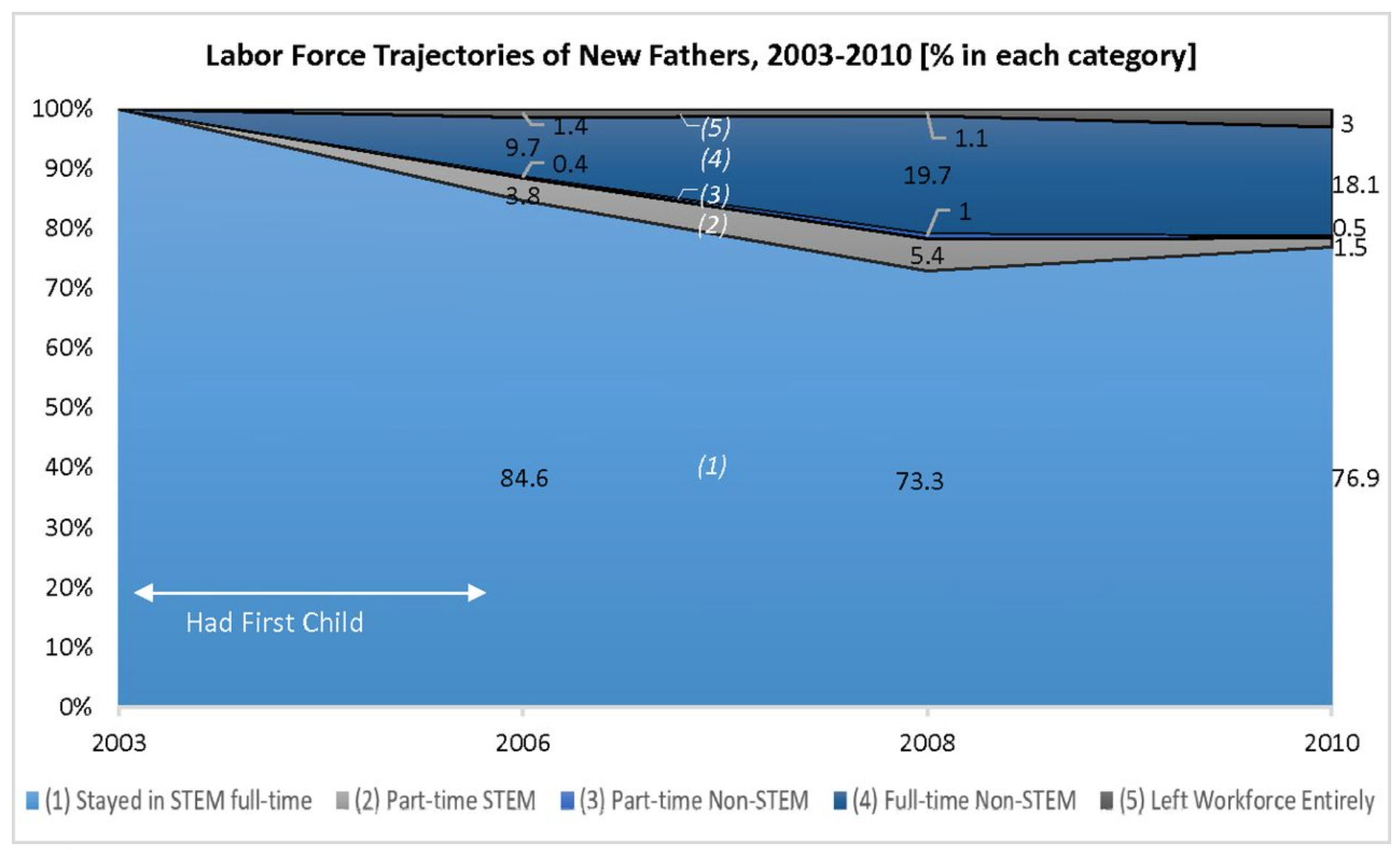

Using National Science Foundation data on STEM professionals -- about 10 percent of whom were academic scientists, representative of national trends -- the authors found that 43 percent of women and 23 percent of men left their full-time jobs within seven years of having or adopting a child.

The finding was consistent across STEM fields in the period studied, from 2003 to 2010. But parents in the life sciences were even more likely than their engineering peers to leave the work force.

New mothers were more likely than new fathers to switch to part-time jobs or cease working outside the home altogether. And both moms and dads were more likely than their childless colleagues to attribute their departures from the field to family concerns.

These parents didn’t appear to return to the STEM work force once their children reached school age, either.

The paper, called “The Changing Career Trajectories of New Parents in STEM,” argues that parenthood is actually an understudied piece of the attrition puzzle in the sciences: other points of the so-called leaky pipeline get more attention, it says. So using longitudinal survey information from the Scientists and Engineering Statistical Data System, the researchers followed a representative national sample of initially childless, full-time STEM professionals -- some of whom had their first child at the beginning of the eight-year study period.

Source: Cech and Blair-Loy

“These professionals were rich in human capital, having successfully completed college- or graduate-level training and being employed in a STEM field,” the study says. “They also demonstrated commitment to full-time work in these male-dominated, math-intensive fields and had moved beyond the key attrition points of education and the school-to-work transition. The exit of these trained and experienced professionals from the STEM workforce would be disadvantageous for both the organizations that employ them and for U.S. STEM industries broadly.”

The researchers compared respondents who had their first child between the first and second survey waves (841 scientists) with those who remained nonparents through 2010 (3,365 scientists).

Asked about the implications of her work for academic STEM in particular, co-author Mary Blair-Loy, professor of sociology at the University of California, San Diego, said there is “some evidence that faculty are subject to challenging cultural pressures to demonstrate their devotion to academic science as a vocation.”

Family caregiving or other aspects of a “rich personal life are still often viewed as distracting and even polluting to a scientific calling,” Blair-Loy said. Such “devaluation of motherhood and caregiving” is a historical artifact from a time when women were excluded from academic life and men weren’t (for a variety of reasons) involved caregivers, she added.

Artifact or not, parent pressure is real -- and “arbitrary,” she said. That is, a “meaningful and close set of family and personal obligations” does not automatically reduce academic productivity, Blair-Loy added. But women face the assumption that it does. And these cultural pressures may even discourage talented early-career scientists, including Ph.D.s and postdoctoral fellows, from entering faculty work.

Lead author Erin Cech, assistant professor of sociology at the University of Michigan, said that from a business case perspective, the level of attrition she and Blair-Loy found is a problem across STEM. It may be “especially problematic” within colleges and universities, though, she said. That’s because it’s “expensive and time-consuming to replace highly educated STEM professionals in academia, and taxes the resources and people power of departments and institutions.”

Robust parental leave policies may help mitigate that, Cech said. But they must "be matched with institutional and departmental cultures" that don't "stigmatize faculty and research staff for taking advantage of those policies.” (Cech and Blair-Loy have previously studied the negative effects of “flexibility stigma,” or the devaluation of workers who need or use flexible work arrangements, on academic scientists.)

Cech said that academic positions often offer greater day-to-day flexibility than positions in industry or government. But that flexibility is not matched by cultural expectations about making use of that flexibility for caregiving.

Jessi Smith, associate vice chancellor for research and professor of psychology at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, has studied women in STEM and advocated work-life integration -- not work-life “balance,” which she said indicates that something “has to give.” She said the new paper illustrates “the big-picture problem of a work force developed by men, for men, at a time when men were the traditional breadwinners and women were the traditional caretakers.”

Why hasn’t the workplace changed, she asked? The STEM workplace, academic or otherwise, "is simply not set up to support parents.”

Smith said that those who are so motivated will “want to interpret" this new research as supporting a kind of “choice narrative” that blames parents for opting out of work. But not only does that view “let the workplace off the hook for taking any responsibility” to change to support parents, she said, “it also assumes that choices are made in a vacuum.”

Parents are choosing to leave a “hostile, nonsupportive workplace” because there is no “viable alternative, except going part-time or exiting altogether.” In other words, Smith said, “Childcare is so very expensive, the tenure-track punishes people who cannot devote 80 hours-plus a week to their work, and the tenure clock timeline coincides with women’s reproductivity years.”

People can pause the tenure clock, Smith added, “but then bias creeps in with, ‘Well, she really had an extra year,’ and, ‘She just had another child because she was in research trouble.’ Yes, I have heard it all.”

Over all, Smith said the new paper is important because it's important to understand that parenthood is a barrier to participation in any work force, “even within academia, where we assume autonomy and flexibility reign supreme."

Just “don’t be tempted to call it a choice,” Smith warned. “The choice between rock and hard place is never a real choice.”

Stephen Ceci, Helen L. Carr Professor of Developmental Psychology at Cornell University, has found that women’s life choices, whether voluntary or constrained, have more to do with their underrepresentation in STEM than gender bias in those disciplines.

Of the new paper, Ceci said that Mary Anne Mason’s “baby penalty” and other, similar research have long documented that even the intention to become a parent comes at a career cost for academics. So what Cech and Blair-Loy’s paper “tells us is that the magnitude of this attrition is large,” or nearly twice as large for women than men, and not confined to academic STEM, he said.

Ceci and his longtime collaborator Wendy Williams, professor of human development at Cornell, have faced criticism -- including from Smith -- for framing the work-family issue as one of choice. But Ceci said that he and Williams have long pushed for institutional policies on caregiving leave and “massive changes in the cultural expectations about caregiving responsibilities and whose career should be privileged.” Examples of the latter include allowing greater flexibility on grants to accommodate new parents, travel with children to conferences and flexible work scheduling.

Noting that the situation might even be worse in nonacademic STEM jobs, Ceci said that employers “really must acknowledge" the substantial burdens of parenthood, which should "not be shouldered largely by new mothers and new fathers.”

Why? When highly educated professionals leave the work force, he said, echoing the new paper, it’s “a loss for all of us.”