You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A growing number of college students are from poor families, but they’re mostly attending less selective institutions, which may decrease their chances of earning a bachelor’s degree.

A new report from the Pew Research Center released Wednesday found that the overall number of undergraduates at U.S. colleges and universities has increased during the past 20 years, with students of color and those from low-income families making up much of that growth. Those students are mostly attending the least-selective colleges and universities, which tend to have fewer resources to help students succeed.

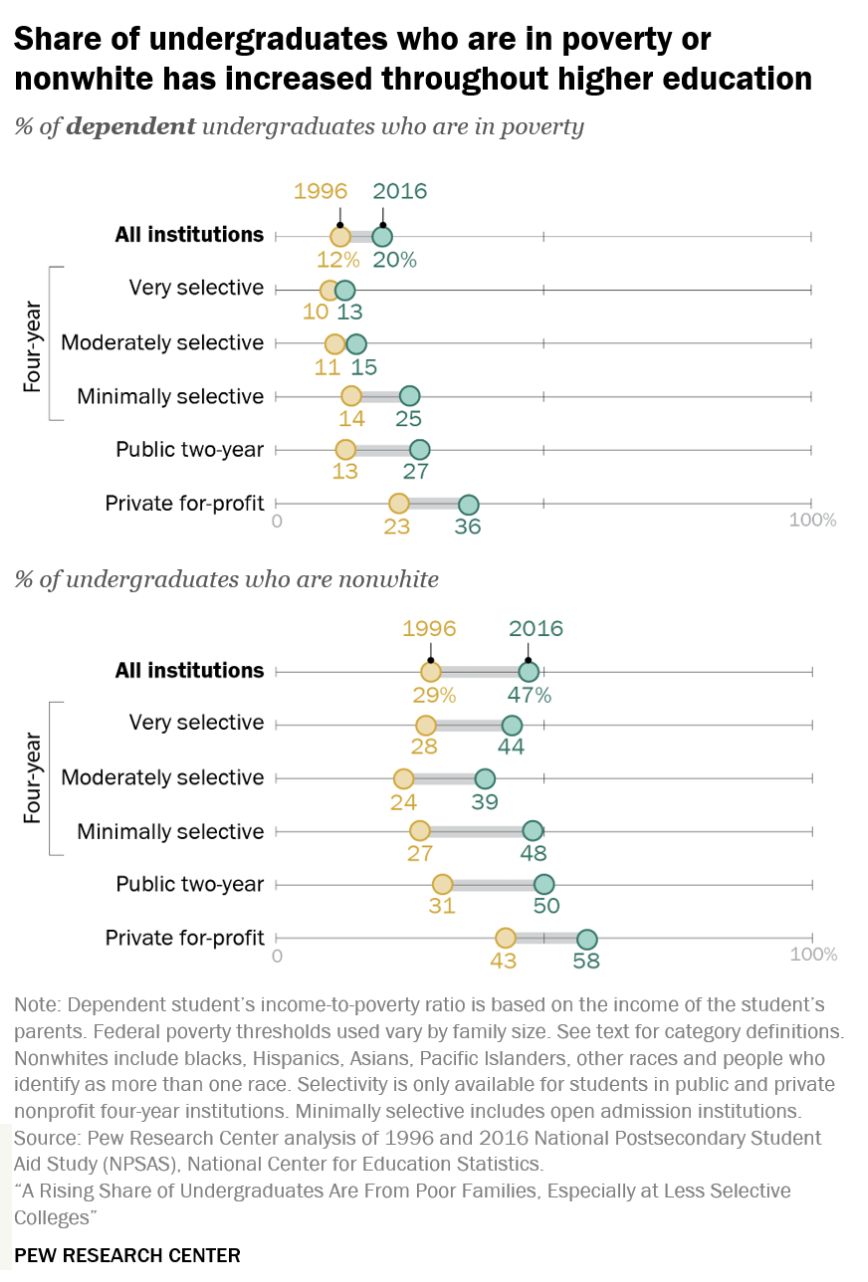

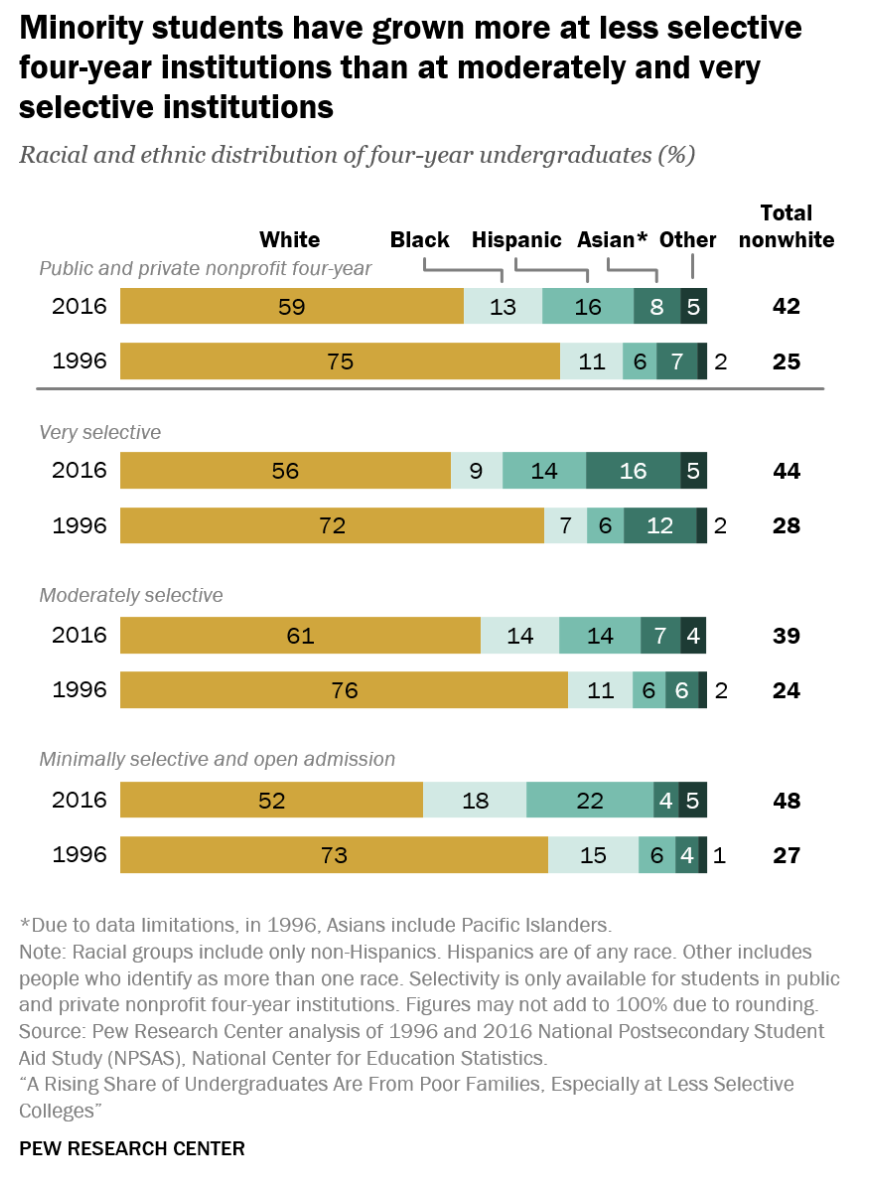

The total share of undergraduate college students who come from poor families increased from 12 percent in 1996 to 20 percent in 2016, according to the report. The number of undergraduates who are nonwhite also increased from 29 percent in 1996 to 47 percent in 2016. The report focused on the financial status of dependent students who are under age 23, unmarried and childless.

“This is a positive development of something that had been a concern, and what the data shows are that many more students from poor families are attending colleges and universities,” said Richard Fry, a co-author of the report and a senior economist at Pew. “On the other hand, when we look at what employers pay, there is a premium for bachelor's degrees … and you’re more likely to get a bachelor’s degree at more selective institutions or at a four-year college rather than a community college.”

While there are more students from low-income families attending all types of colleges and universities, Pew found that their growth at selective institutions is less pronounced than at less selective four-year, two-year and for-profit colleges.

The percentage of low-income, dependent undergraduates attending “very selective” institutions increased from 10 percent in 1996 to only 13 percent in 2016, according to the report. Meanwhile, at public two-year colleges, the number of low-income students increased by 14 percentage points, to 27 percent, over the same 20-year time period.

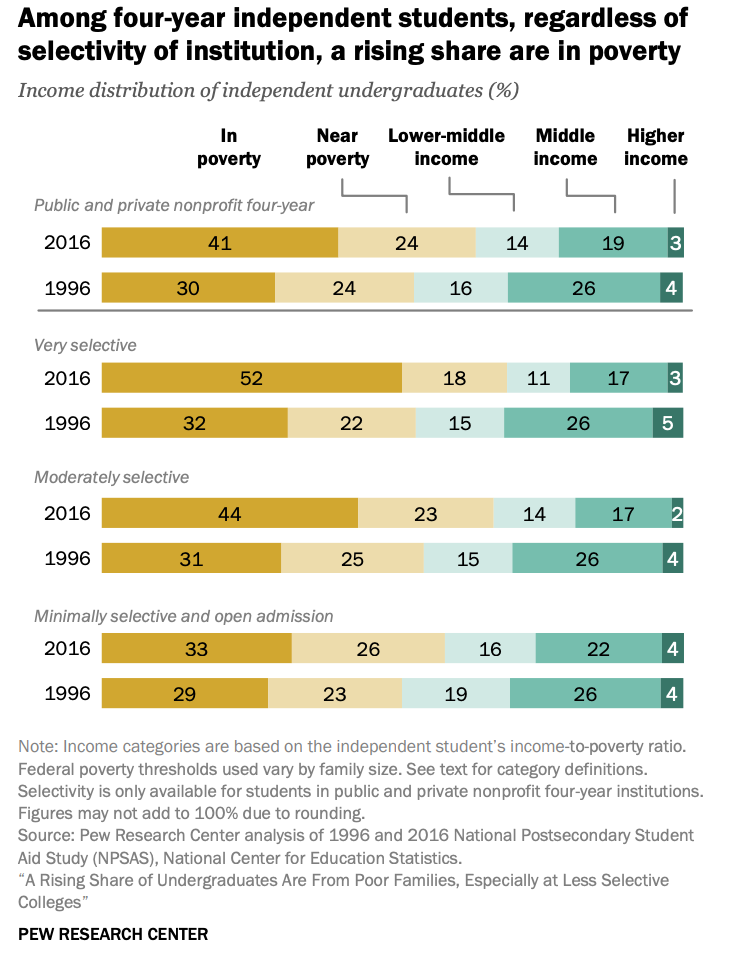

Although the report focuses on young, dependent students who presumably receive financial assistance from their parents or other family members, it also shows that there are more independent students living in poverty compared to 20 years ago. Among independent students, 42 percent were living in poverty in 2016 compared to 29 percent in 1996.

Jason Delisle, a resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, said selective universities should receive more credit from the Pew researchers for enrolling more low-income students today than they did 20 years ago. Furthermore, these institutions also are enrolling more independent students, who tend to be poorer than dependent students, he said.

The Pew study found that among independent students at four-year institutions, 52 percent were poor and attended a “very selective” institution in 2016, which reflects a 20 percentage point increase from 1996.

“For all the hand-wringing about affordability, it appears that … a larger proportion of the student body is low income despite all these scary stories about affordability,” Delisle said. “One thing we do know is that the selective colleges are keeping prices really low for these students. The net price after inflation that students pay for tuition at really selective colleges has barely budged in 20 years.”

According to the College Board, the average annual net tuition and fees over time for full-time students at private nonprofit universities declined from $15,500 a year in 2007 to about $14,600 in 2018. At public, four-year colleges, the average net tuition and fees increased by about $600, from $3,100 per year in 2007 to about $3,700 in 2018.

For-profit institutions saw the share of dependent low-income undergraduates increase, as well, from 23 percent in 1996 to 36 percent in 2016 -- a 13-percentage-point gain.

“Selectivity does matter,” Fry said. “It is noteworthy that students from lower-income backgrounds are in higher education but disproportionately at least-selective colleges and universities, and that will impact their likelihood of getting a degree.”

Robert Kelchen, an assistant professor of higher education at Seton Hall University, said this trend is concerning.

“These are the [institutions] with fewer resources, and among the public [colleges] they get less in state funding even as their students come with greater need,” he said.

Kelchen said states ultimately need to rethink how they fund their colleges and universities.

“It’s not enough to get a small number of low-income students into a flagship university,” Kelchen said. “How are states funding their colleges in a way that helps reduce gaps in degree attainment?”

A recent report from the Century Foundation called for more public investment in the country’s community colleges because of the growing number of low-income students enrolling. The report blamed low completion rates on a lack of state higher education funding. The report states that private, four-year colleges spend an average of $72,000 per full-time student each year, which is five times more than the $14,000 community colleges typically spend per student. Public universities spend $40,000 each year on each full-time student.

Even when research spending is excluded, private universities spend triple what community colleges do, and public four-year institutions spend 60 percent more.

“The research suggests going to a flagship public university pays off in the long term, but for many students, going hundreds of miles to a flagship isn’t possible,” Kelchen said. “The open-access institution is what’s close by, and that’s why they’re going. Even giving students more financial aid to go to a selective college may not be enough to change their decision if they have to go 300 miles away.”

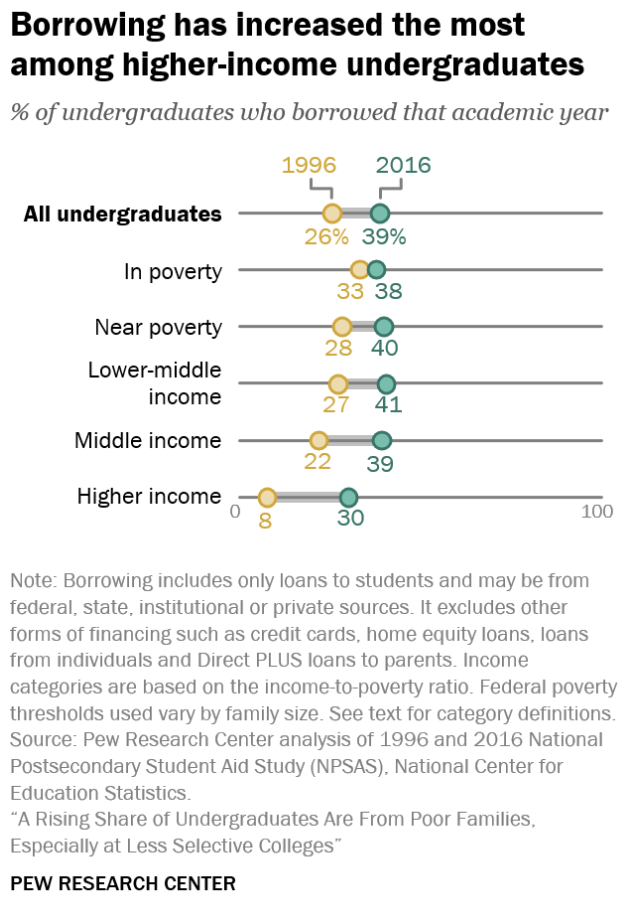

Even with significant numbers of low-income students going to college, they are no more likely to take out loans than any other undergraduate, according to the Pew report. Borrowing has increased the most among higher-income students, the report said.

Thirty-three percent of students in poverty borrowed for their education in 1996, compared to 8 percent of higher-income students. But in the years since then, borrowing increased among high-income students to 30 percent, while 38 percent of poor students took out loans in 2016.

"High-income families are choosing to attend very expensive schools, and they may need the loans to do it," Delisle said. "The student loan program is as much a loan program for high-income families attending elite institutions as it is low-income families attending less selective ones."

Delisle said another reason low-income students' borrowing habits haven’t changed much is that they’re attending less selective, lower-cost colleges and receiving financial aid packages that will cover their tuition and fees.

“The amount of loans they have to take out is covering living expenses, and the decision around how much to borrow can be flexible,” he said.

Despite the increased numbers of poor students attending community college over the past 20 years, the overall share of undergraduates at two-year colleges has decreased. Community colleges educated 44 percent of the undergraduates in college in 1996, but only 36 percent of all students attended a two-year college in 2016, according to the Pew report.

“What used to be classified as a two-year college or community college has shifted over the past 20 years, and now, they’re granting bachelor’s degrees,” Fry said. “But I don’t think it explains it all -- there have been some other demographic changes in the nation’s undergrads. More of them are traditional age, 18 to 24, fewer are older or nontraditional students, and that sort of demographic shift lends itself more to a four-year college than community college.”

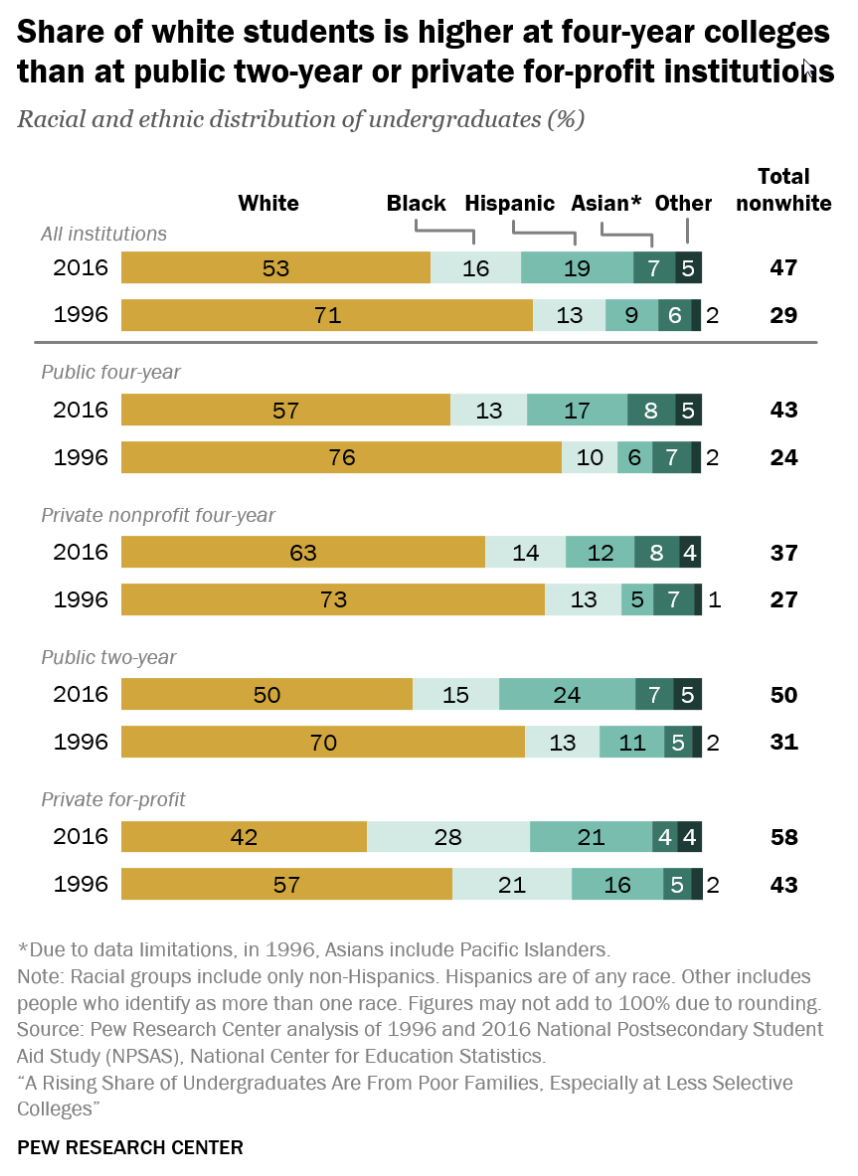

The Pew report also found that the growth of nonwhite students in colleges and universities reflects the growing number of Hispanic students pursuing education beyond high school. And for the first time, Hispanics are now the largest minority group among the nation’s undergraduates over all; there are now as many Hispanic undergraduates as African Americans at moderately selective institutions.

Fry said there shouldn’t be much surprise that the population of Hispanic undergraduates has grown, since they became the largest minority group among high school graduates in 2008. But another reason why more Hispanics are attending college is that high school dropout rates among this group have decreased.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the Hispanic high school dropout rate decreased from 27.8 percent to 8.6 percent from 2000 to 2016.

“Both higher education and K-12 can take some credit for this,” Fry said. “Yes, the high school dropout rates have come down a lot, but among the high school graduates, there is a notable increase in the share of Hispanic graduates going on to college.”