You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

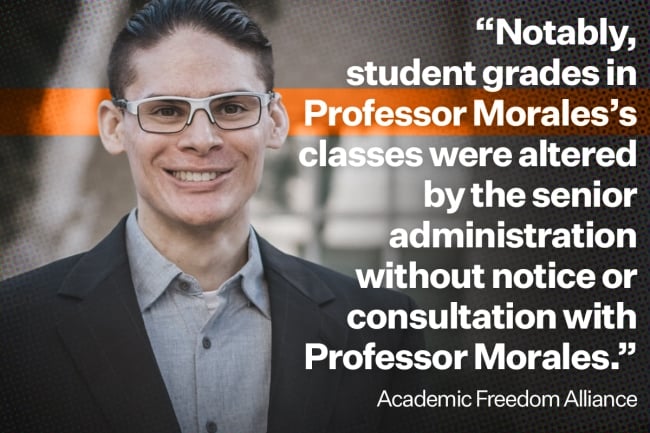

Kendrick Morales was a tenure-track assistant professor of economics at Spelman College.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Photo: Kendrick Morales

A former assistant professor of economics at Spelman College says the institution bumped up the grades he gave students without informing him beforehand and, after he complained, fired him without giving him the right to appeal.

Kendrick Morales said he worked at the college for two years, in a tenure-track position, before it ousted him this summer.

“I was planning to teach in the fall, which was like a couple weeks later,” Morales told Inside Higher Ed. “They didn’t give me any kind of warning.”

Calculations he provided suggested significant percentages of upperclassmen, including seniors in a thesis class, were set to fail a few of his courses even after his own substantial scaling up of their scores. He said the college surreptitiously intervened to further increase grades in two classes.

Among the emails and documents Morales provided about his situation is one suggesting that administrators changing grades might be a broader issue at Spelman.

“I brought your issue to Faculty Council and some of them experienced what you did,” Lisa B. Hibbard, the then president of Spelman’s Faculty Council, wrote in an April email to Morales that he provided Inside Higher Ed. “They all agreed that grades are at the discretion of the instructor only, no one else.”

Hibbard didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The private Atlanta institution, a historically Black college for women, responded to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for an interview with a statement that neither confirmed nor denied the authenticity of Morales’s documents. The individual leaders Morales mentioned as being involved in his situation didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“Meaningful and effective classroom engagement is the hallmark of a Spelman education,” the college said in the statement. “The college, its administrators, and faculty exercise appropriate judgment in the delivery of our learning activities in order to maintain consistency across Spelman’s campus.”

The statement also said the college “reviewed this matter and has no further comment on the opinions of this former faculty member. Since this is a confidential employment matter, we decline to comment further.”

The Academic Freedom Alliance—a group that supports faculty free expression, including through raising legal funds and promoting the Princeton Principles for a Campus Culture of Free Inquiry, which is supported by many political conservatives—issued a news release last week calling for Morales’s reinstatement. It noted it had sent a Nov. 12 letter to Spelman president Helene D. Gayle.

“If the grading is done pursuant to an honest evaluation, sanctioning a professor for grading students too rigorously amounts to punishing him or her for being truthful about the quality of the students’ work—that is, punishing the instructor for fulfilling the institutional and fiduciary duty to honestly pursue truth,” the AFA’s letter said. “Giving students grades that a competent instructor has concluded, using his or her professional judgment, are not merited is a form of intellectual fraud.”

Failure Rates

Morales said that, before going to Spelman, he was a solo instructor of probability and statistics one summer at the University of California, Irvine. As a Ph.D. student at Irvine, he was also a teaching assistant for 15 quarters and four summers, assisting in probability and statistics and applied econometrics, he said.

He taught three courses during his two years at Spelman: econometrics, principles of macroeconomics and senior thesis. He said the grade-changing issue began with his econometrics section in fall 2021, his first semester there.

He provided Inside Higher Ed calculations of how many students would have failed each of his classes without any of his own grade scaling. For that fall 2021 econometrics section, a class consisting of only juniors or seniors, the failure rate would’ve been about 89 percent.

According to a narrative Morales published in The Free Press, on the midterms for that class, during which he allowed students to use his lecture notes, the highest grade was a 95—but the next highest was a 72. He asked the economics department chair for advice. She told him he should raise all the midterm scores by 28 points, and he did so, he wrote.

That chair, Marionette Holmes, didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment.

Regardless, Morales wrote that the students “peppered me with complaints” about the midterm. But he wrote that he continued teaching the same way as before. The students all began attending virtually instead of in person, and most stopped doing the coursework. Many complained to the chair about their grades the Friday before the final, he wrote.

He wrote that their scores on the final exams were even worse, and he knew the chair would insist on raising them—so he “pre-emptively” raised them 36 points, making a 57 an A.

After his own scaling up of grades, 44 percent of that class would still fail it, according to the calculations Morales provided Inside Higher Ed.

He said the students complained to the undergraduate studies dean, Desiree Pedescleaux, who didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment. Morales said he didn’t hear from Pedescleaux about what she had done in response until February of this year—after pressing his department chair to learn what had happened.

Morales’s chair mentioned Pedescleaux helping the fall 2021 students, he said. After he asked Pedescleaux herself for more information, she sent him an email saying the college had increased grades in both his econometrics and principles of macroeconomics courses.

“Based on our fact gathering, our office determined that some adjustments were warranted,” Pedescleaux wrote. She said fewer than three “bonus points” were added for both classes.

“This resulted in a slight bump in the overall final scores, and in some cases, it resulted in grade changes, mostly for students already earning a C or better,” she wrote. “For students resting at the bottom of the grading scale, there was not much that could be done without drastically changing the grading scheme.”

Her email ended with “P.S. I regret to inform you that we have two additional class grievances. I will be in touch shortly to discuss them.”

‘Unsatisfactory’ Teaching

Morales said the only course in which he didn’t scale up grades himself was his fall 2021 principles of macroeconomics course, where the fail rate (he defined this as getting a letter grade below a C) was 22 percent.

A couple of classes, the spring and fall 2022 senior thesis sections, had no failures after he applied his scaling. But the fail rate, even after his scaling, was 43 percent for the spring 2023 senior thesis. Morales said he had agreed to teach two thesis sections at the same time that semester.

For that last course, Morales’s department chair and two fellow faculty members did a review and unanimously found his teaching to be “unsatisfactory,” according to the review Morales provided. Only one of the three reviewers responded to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for comment, but the one who did declined to answer questions.

“Over 24 semester class meetings, Dr. Morales meets with his students in person for 15 minutes twice a week” was among the reviewers’ comments.

“Dr. Morales MUST [emphasis in original] improve his feedback mechanism and communications in his syllabus,” they wrote. “Dr. Morales MUST meet for longer periods of time with the students (i.e. for the full 150 minutes of face to face contact hours per week).” They also said he was required to provide frequent assessments of students’ work and use a rubric.

Morales told Inside Higher Ed that he thinks the negative review was to “set me up for my ultimate dismissal.”

He said he had complained to interim provost Dolores Bradley Brennan about the grade changes and, while Bradley Brennan had said she was satisfied with Pedescleaux’s response, she set up a July 26 virtual meeting with Morales. He wrote in The Free Press that he looked forward to discussing the grade changes with her, but she used the meeting to fire him.

Bradley Brennan, now Spelman’s vice provost for faculty, didn’t respond to Inside Higher Ed’s requests for an interview. Morales provided the separation letter she signed, which mentions, among other things, students’ “significant complaints about certain of your grading practices” in fall 2021.

“As the fall 2022 semester was under way, student complaints regarding your courses quickly resurfaced,” she wrote, mentioning again grading issues, plus concerns about Morales’s “accessibility.”

“These concerns continued and grew even more significant in spring 2023, particularly in your thesis course,” Bradley Brennan wrote. “By way of example only, students complained that instead of conducting full class sessions, you only led brief meetings lasting at sometimes no more than fifteen minutes.” She said his contract wouldn’t be renewed and he shouldn’t return to campus, but he’d still be paid for fall 2023.

Was changing Morales’s assigned grades an academic freedom violation? In its letter, the Academic Freedom Alliance wrote, “Spelman College’s actions in this matter involve important issues at the heart of the academic and scholarly enterprise. Members of the faculty must have the freedom honestly to assess the quality of the academic work of students … Fundamental principles of academic freedom require assessment of individual student performance to be made by the teaching staff appointed to teach each course.”

Greg Scholtz, director of the American Association of University Professors’ Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance, said, “This is kind of Academic Freedom 101—that administrators don’t change professors’ grades.”

The AAUP does have a recommended policy in which the “department head” or “the instructor’s immediate administrative superior” can change a student’s grade. But that’s only after the professor is given a say before a committee composed of faculty members in the instructor’s department or closely allied fields, and the committee still recommends changing the grade. Of grading, Scholtz said, “This is a place where there’s a great deal of pressure on academic freedom—especially now, where many institutions are suffering from enrollment declines … the pressure to keep the customer satisfied is strong, and you also have parents paying much more attention.”

Morales said he doesn’t know whether it’s worth it to try to get his Spelman job back—he mentioned a lack of autonomy as a teacher, and he’s mulling leaving academia entirely.

In additional written comments to Inside Higher Ed, Morales said that if Spelman doesn’t respond to the Academic Freedom Alliance’s letter, “then I very much hope the AFA will continue to support me in taking further action (legal or otherwise) against Spelman to address my situation and further expose these administrator practices.”

He said it’s “not only in the interest of faculty to stand up for their academic freedom protections whenever they are violated, but it’s also in the interest of the public as well, particularly in my case, to make sure that colleges and universities cannot get away with potentially defrauding the public through the explicit falsification of grades and degrees.” He told Inside Higher Ed he was trying not to lower standards for students.

“I do feel like I gave them a very good chance to learn the material,” he said.

“There’s always going to be the opportunity to blame others for failure or not being the best version of yourself that you can be,” he said.