You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Higher education workers don't have the same purchasing power as they did before the pandemic.

mphillips007/iStock/Getty Images Plus

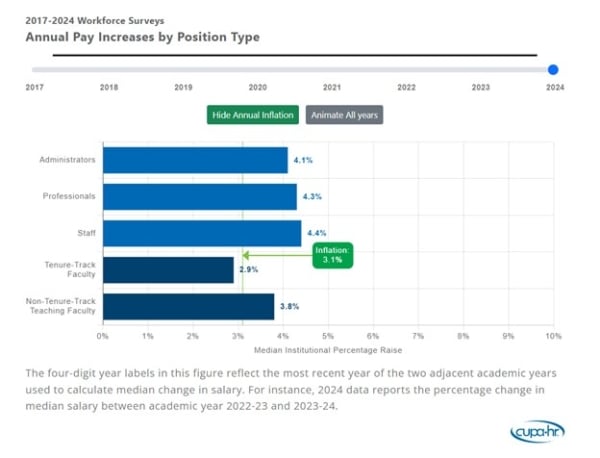

Many higher ed employees got pay increases this past year that exceeded the inflation rate for the first time since the pandemic, but they still don’t have the same buying power as before the public health crisis/emergency, according to a new report by the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR).

“The great news is that it seems like higher education institutions are trying to find the money in their budgets to respond to the fact that inflation has been high. But it’s not been enough,” said Melissa Fuesting, senior survey researcher at CUPA-HR and lead author of the report. “All higher ed employees’ purchasing power has been eroded since the pandemic.”

The organization analyzed eight years of salary data for tenure-track, nontenure track and staff positions from more than 450 colleges and universities to calculate the median institutional change in average salary. It used the Consumer Price Index to compare inflation with the percentage in change of the average salary paid by an institution from year to year.

College and University Professional Association for Human Resources

This was the first year since the pandemic that the median pay increases for the majority of employees surpassed the annual inflation rate (which was 3.1 percent), according to the report.

“Raises this last year beat inflation, but they haven’t been beating inflation since the pandemic,” Fuesting said. “The consequence is that it could have an impact on retention, which can really impact an organization. You lose institutional knowledge and great talent.”

A 2023 report from CUPA-HR showed that turnover for higher education employees doubled between 2020 and 2022, and that an opportunity for higher pay was the single biggest reason why those workers quit. The report the organization released Wednesday offers more insight into how different employee groups’ salaries have fared since the pandemic.

Compared to teaching positions, median salaries of staff members saw the largest increase over the past year (4.4 percent) and have experienced the smallest inflation-adjusted pay gap since the pandemic. Adjusting for inflation, their median earnings during the 2023–24 academic year were 0.3 percent less than during the 2019–20 academic year.

And while nontenure-track teaching faculty received their biggest annual raise in eight years (median salaries increased by 3.8 percent), their post-pandemic purchasing power is 8.2 percent less than what it was in 2019.

“Some of what we see there could be a reflection of the success of unions and collective bargaining,” said Kevin McClure, an associate professor of higher education at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, who noted the surge in organized labor campaigns among higher education workers. “They’ve been able to secure substantive pay increases and in some cases, bring up the minimums they’re paid per class or per year.”

Tenured track faculty, however, were the only group whose median pay raise (2.9 percent) this year did not surpass the annual inflation rate. Adjusting for inflation, they earned 9.7 percent less this academic year than they did prior to the pandemic.

It’s not necessarily surprising that faculty—who generally have two chances at promotion throughout their careers—have experienced much bigger dips in the purchasing power of their salaries than staff, said McClure.

“We also tend to not have as many opportunities to move to other jobs. Faculty jobs can be in some cases scarcer compared to staff positions. We can be more bound to an institution if we’ve earned tenure there,” he said. “Whereas staff have greater opportunities to move into new positions. And when there’s been turnover in institutional staff, when they hire someone new that person is almost assuredly going to be making more than their predecessor.”

Although many institutions operating with limited resources have offered low salaries for decades, McClure said this new data from CUPA-HR bolsters supports the need for change.

“For a long time, even when pay wasn’t great, institutions could still post a position and a lot of people would apply for it because colleges can still be a really attractive place to work,” he said. “That’s not as much the case anymore. There are some positions that it’s getting really hard to recruit for.”