You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

With rising tuition, families are increasingly concerned about what students can expect after graduation in terms of debt, employment, and earnings. They want to know: What is the value of a college degree? Is it worth the cost? Are graduates getting good-paying jobs?

At the same time, state and federal policymakers are sounding the call to institutions for increased accountability and transparency. Are students graduating? Are they accruing unmanageable debt? Are graduates prepared to enter the workforce?

Colleges and universities struggle to answer some of these questions. Responses rely primarily on anecdotal evidence or under-researched and un-researched assumptions because there are little data available. Student data are the sole dominion of colleges and universities. Workforce data is confined to various state and federal agencies. With no systematic or easy way to pull the various data sources together, colleges universities have limited ability to provide the kind of analysis of return on investment that will satisfy the debate.

But access to unit-record data — connecting the student records to the workforce records — would allow institutions to discover those answers. What’s more, it would give colleges and universities the opportunity to conduct powerful research and analysis on post-graduation outcomes that could shape policies and program development.

For example, education provides a foundation of skills and abilities that students bring into the workforce upon graduation. But how long does this foundation continue to have a significant impact on workforce outcomes after graduation? Research based on unit-record data can also show the strongest predictors of student earnings after graduation — educational experience, the local and national economy, supply and demand within the field, or some combination of each.

President Obama and others have proposed that colleges share such information, and many colleges have objected. They have suggested that the information can’t be obtained; that data would be flawed because graduates of some programs at a college might see different career results than others at the same institution; that such a system would jeopardize student privacy; that it would penalize colleges with programs whose graduates might not earn the most one year out, but five or more years out.

At the University of Texas System, we have found a solution – at least within our own state – and, for the first time, are able to provide valuable information to our students and their families. We are doing so without assuming that data one year out is better or worse than a longer time frame – only that students and families should be able to have lots of statistics to examine. We formed a partnership with the Texas Workforce Commission that gives us access to the quarterly earnings records of our students who have graduated since 2001-02 and are found working in Texas. While most of our alumni do work in Texas, a similar partnership with the Social Security Administration might make this approach possible for institutions whose alumni scatter more than ours do.

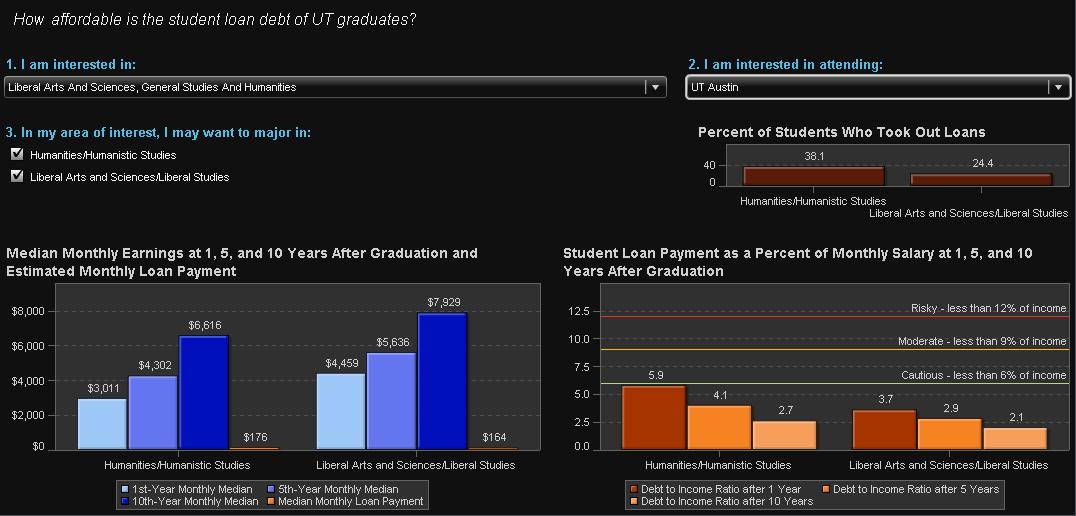

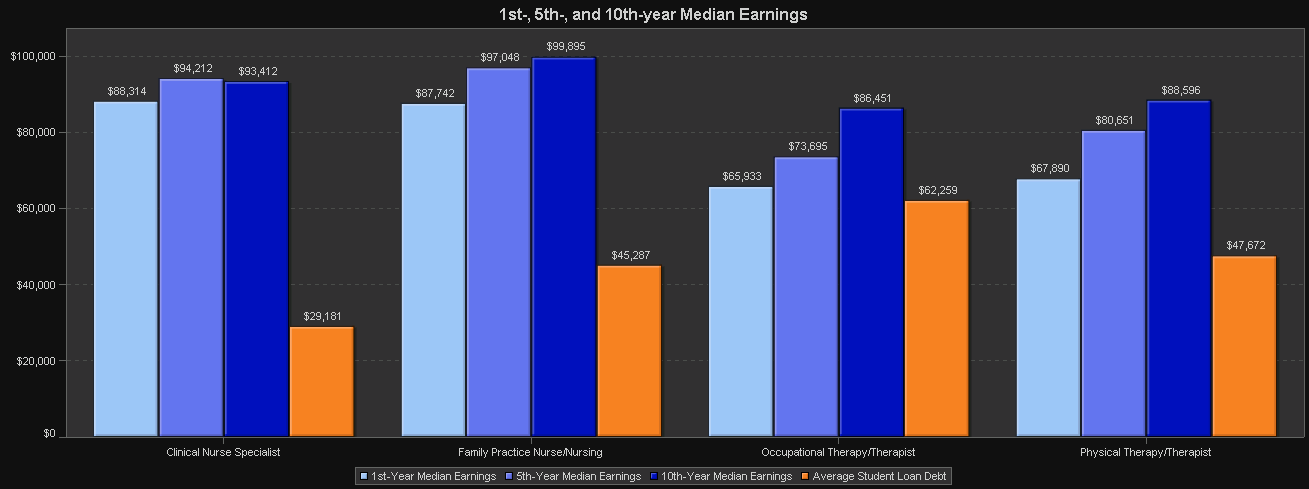

With that data, we created seekUT, an online, interactive tool — accessible via desktop, tablet, and mobile device — that provides data on salaries and debt of UT System alumni who earned undergraduate, graduate, and professional degrees for 1, 5, and 10 years after graduation. The data are broken down by specific degrees and majors since we know that an education major and an engineering major from the same institution – both valuable to society – are unlikely to earn the same amount. Also, seekUT introduces the reality of student loan debt to prospective and graduate students. In addition to average total student loan debt, it shows estimated monthly loan payment alongside monthly income, as well as the debt-to-income ratio. And because this is shown over time, students get a longer view of how that debt load might play out over the course of their career as their earnings increase over time.

When we present data in this way, we provide students information to make important decisions about how much debt they can realistically afford to acquire based on what their potential earnings might be, not just a year after graduation, but 5 and 10 years down the road. Students and families can use seekUT to help inform decisions about their education and to plan for their financial future.

Admittedly, it is an incomplete picture. Many of our graduates, especially those with advanced degrees, leave the state. If they enroll elsewhere to continue their education, we can discover that through the National Student Clearinghouse StudentTracker. But for those who are not enrolled, there is no information. In lieu of a federal database, we are exploring other options and partnerships to help fill in these holes, but, for now, there are gaps.

With unit record data we can inform current and prospective students about past performance for graduates in their same major; this is a highly valuable product of this level of data. Access to this information in a user-friendly format can directly benefit students by offering real insights — not just alumni stories or survey-based information — into outcomes. The intent is not to change anyone’s major or sway them from their passion, but, instead, to help students make the decisions now that will allow them to pursue that passion after graduation.

There are a multitude of areas we need to explore, both to answer questions about how our universities are performing and to provide much-needed information to current and prospective students. The only way to definitively provide this important information is through unit-record data.

We recognize that there are legitimate concerns, especially given the nearly constant headlines regarding data breaches, about protecting student privacy and data. And the more expansive the data pool, the larger and more appealing the target. A federal student database may be an attractive target to hackers. But these risks can be mitigated — and are, in fact, on a daily basis by university institutional research offices, as well as state and federal agencies. We safeguard the IDs, locking down access to the original file, and not using any identified data for analysis. And when we display information, we do not include any data for cell sizes less than five. This has been true for the student data that we have always held. Given these safeguards, I believe that the need for the data and the benefits of having access to it far outweigh the risks.

seekUT is an example of just some of what higher education institutions can do with access to their workforce data. But for all its importance, seekUT is a tool to provide users access to the information, to inform individual decisions. It is from the deeper research and analysis of these data, however, that we may see major changes and shifts in the policies that impact all students. That is the true power of these data.

For example, while we are gleaning a great deal of helpful information studying our alumni, this same data gives us insights into our current students who are working while enrolled. UT System is currently examining the impact of income, type of work, and place of work (on or off campus) on student persistence and graduation. The results of this study could have an impact on work-study policies across our institutions.

Higher education institutions can leverage data from outside sources to better-understand student outcomes. However, without a federal unit record database, individual institutions will continue to be forced to forge their own partnerships, yielding piecemeal efforts and incomplete stories. We cannot wait; we must forge ahead. Institutions of higher education have a responsibility to students and parents and to the public.