You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

One of the most important developments out of Silicon Valley in the past decade is not a technology but a concept. A minimum viable product -- or MVP -- is the simplest, smallest product that provides enough value for consumers to adopt and actually pay for it. It also is the minimal product that allows producers to receive valuable feedback, iterate and improve. A minimum viable product is one of the core tenets of the so-called lean start-up and explains why many technology entrepreneurs are able to launch businesses with practically no investment at all.

For example, the Zappos founder Nick Swinmurn famously launched his business not by investing millions in an e-commerce backend, but by simply taking photos of desirable shoes at shoe stores and posting them online. When customers clicked buy, Swinmurn went to the store, bought the shoes, shipped them -- repeating hundreds of times before getting the necessary feedback to validate further investment in Zappos.

College as we know it is the polar opposite of a minimum viable product. A bachelor’s degree is neither simple nor small. It wasn’t constructed to encourage colleges and universities to iterate and improve. And it’s certainly not minimizing anyone’s investment. Which is why the most important development in higher education in the next decade will be a College MVP.

***

Some of the lean start-ups proliferating in Silicon Valley and elsewhere are boot camps, providing “last-mile” training to unemployed, underemployed and unhappily employed young people and -- critically -- placing them in good jobs in growing sectors of the economy, like technology and health care. This largely technical training is increasingly referred to as last mile not only because it leads directly to employment, but reflecting the last mile in telecom, where the final telephonic or cable connection from trunk to home is the most difficult and costly to install, and also the most valuable.

Boot camps like Galvanize, Revature and AlwaysHired are busy installing these last-mile connections. Making and maintaining connections to employers is complicated and costly -- exponentially more so than developing new academic programs in isolation.

As these connections are made and reinforced, last-mile providers will be tempted. While today they’re serving a population that is roughly 90 percent college graduates, some are already spying a larger opportunity than simply serving as a top-up program for bachelor’s degree completers. Some will be inspired by the Silicon Valley ethos to ask this question: How do we move from “top-up” to “alternative”?

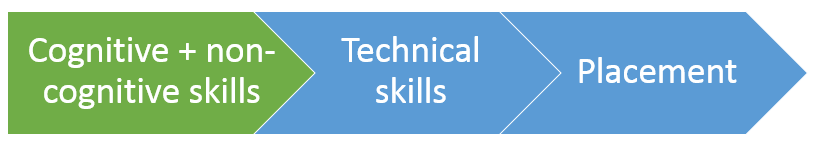

The answer, of course, is by adding a program ahead of the last-mile technical training to form the first stage of a comprehensive pathway to a good first job.

Such a program would equip students with cognitive and noncognitive skills -- not necessarily at the level one would expect of a college graduate, but at the (presumably lower) level employers require for entry-level positions. It would also be much shorter and less expensive than what we know and love as college.

The very concept of a College MVP raises a threshold question: Would any employer hire a candidate with this level of preparation rather than a college degree? Sure, most employers will continue to prefer whole bachelor’s degrees. And many will continue to insist on it. But what if employers could start MVP candidates off at lower salaries? Why? Because MVP graduates won’t have forgone four years of full-time employment and won’t have incurred tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debt.

Another reason to believe employers might take an interest in MVP candidates is that no one -- least of all employers -- knows what cognitive and noncognitive skills are expected of college graduates. Because no one -- least of all colleges -- is measuring anything. Meanwhile, you can bet that last-mile providers who add an innovative College MVP will be asking questions of employers, assessing constantly, measuring and communicating back to employers -- and almost certainly doing a better job of selling their candidates to employers than colleges and universities do.

Finally, employers with any sense of the broader socioeconomic context will - when presented with a potentially viable alternative -- recognize that requiring a whole bachelor’s degree excludes virtually half the work force, many of whom might be great fits.

***

Be disrupted or disrupt thyself? Many colleges and universities will face this choice in a few years. While last-mile providers will be first to market with College MVPs, some colleges and universities will see the writing on the wall and attempt to do the same. Here are the challenges they’re likely to face in doing so.

1) Associate Degree Paradigm. Most colleges and universities probably think they have a College MVP. It’s called an associate degree. The problem is that the associate degree is a flawed credential, failing in many cases to prepare students with the requisite cognitive and noncognitive skills required by employers, and giving rise to studies showing half of associate degree holders are underemployed.

The associate degree is a credential that’s derived from and beholden to the bachelor’s degree. In contrast, a College MVP won’t be organized around credit hours or precepts of general education, but will attempt to maximize development of critical thinking, problem solving, communication and teamwork skills in a minimal period of time.

It will also attempt to provide students with cognitive frameworks that facilitate future learning -- on the job and in continuing formal education and training. And while my guess is that College MVPs may look different depending on the industry or even the type of entry-level job, it seems likely that they’ll emerge from a paradigm shift from how we currently think about college -- much more than simply cost and length.

|

TRADITIONAL COLLEGE |

COLLEGE MVP |

|

Faculty-centric |

Employer-centric |

|

Learning outcomes |

Competencies/skills |

|

Curriculum |

Assessments |

|

Assignments |

Work product |

|

Liberal arts |

Critical thinking |

|

Electives |

Prescribed pathway |

Colleges and universities that aspire to develop a College MVP will need to disabuse themselves of the illusion that the associate degree provides a viable model.

2) Building the Last Mile to Employers. Building a College MVP only makes sense if institutions are able to build the last mile to employers, which requires a lot more contact with employers than most colleges and universities are used to having.

The vast majority of colleges and universities continue to believe they’re not in the business of preparing students for their first job, which runs counter to the top reasons matriculating students cite for pursuing postsecondary education, namely to improve employment opportunities (91 percent), to make more money (90 percent) and to get a good job (89 percent). Meanwhile, at most colleges, career services remains the Las Vegas of the university. Northeastern’s co-op program gets so much attention because it’s so rare. It’s also not replicable overnight. Building a network of thousands of employers has taken Northeastern decades.

3) Isomorphism. Perhaps the most significant impediment is cultural. The concept of a minimum viable product is anathema to the culture of higher education. Why would respectable institutions offer less than a bachelor’s degree when their models -- our most elite colleges and universities -- aren’t likely to consider doing so for a very long time? Moreover, higher education reveres tradition, which is too often taken for granted as a signifier of quality -- to the point that U.S. News might as well rank colleges each year based on age. As a result, it’s hard to imagine MVPs popping up at more than a handful of colleges and universities. Which is sad, because tens of millions of Americans could use them right now; college MVPs have the potential to be higher education’s most valuable player.

***

Even if colleges and universities are likely to lag in the emergence of college MVPs, they’re already leading the way in the development of master’s MVPs. When universities like MIT are comfortable rolling out MicroMasters credentials, thousands of institutions are sure to follow.

This is critical, as college MVPs won’t be the end of the postsecondary road for most students. After following a College MVP to last-mile training to placement pathway to a good first job in a growing sector of the economy, subsequent pathways will emerge to equip new employees with the higher-order thinking capabilities required for more complex and managerial positions. Higher education will go from a one- or two-time purchase for most students to a product employees consume as needed throughout their professional lives. And none of the aforementioned barriers to the College MVP are likely to stop colleges and universities from growing significant enrollment in thousands of master’s MVPs.