You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

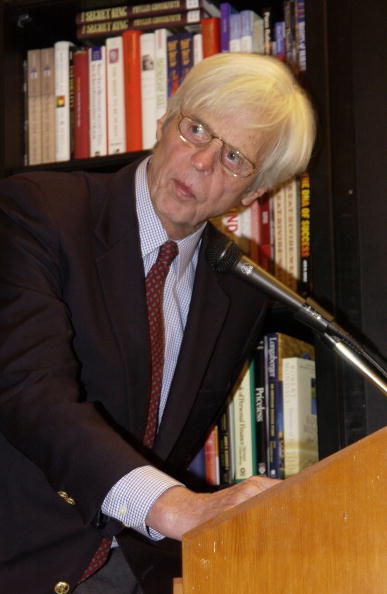

George Plimpton at the 50th anniversary of the 'Paris Review'

Getty Images

The leading contemporary theorist of identity Judith Butler is known for, and often attacked for, having a difficult writing style. But she once explained that, after studying difficult philosophers like Hegel and Heidegger, “I was very much seduced by what I think was a high modernist notion that some newness of the world was going to be opened up through messing with grammar.”

In a similar vein, the ecology-minded theorist Timothy Morton espouses the very abstract object-oriented ontology, premised on the idea that things have their own existence. But he succinctly distinguished it from a standard left position: “In Marxism, there are human economic relations and the universe. It’s a form of reductionism, and everything defaults to the human decider.”

Contrary to the reputation of literary and cultural theory for obscurity, such moments elucidate the thought of these critics. And they occurred not in an article or book but an interview.

Under the radar as a form of scholarly writing, the interview has become a major genre in literary and cultural studies, explaining the gnarly terrain of theory and arcane realms of scholarship. Indeed, in the past decade it has become ubiquitous.

Turn to the pages or scan the sites of Boundary 2; Minnesota Review; Public Culture; Social Text; Symploke; Theory, Culture & Society; Workplace or any number of other critical journals, and you’ll regularly find interviews with critics, theorists and other scholars. They also crop up in books like the Live Theory series from Bloomsbury or collections with individual critics. Added to those academic venues, look at new online reviews such as Los Angeles Review of Books or Public Books, and you’ll find more.

Alongside those, in the past decade, the interview has multiplied in audio or video formats, as well as text, for institutes, centers, departments, publishers and personal websites. The National Humanities Center, for example, features video interviews with selected fellows, and the publisher Verso has recently added text and video interviews with theorists such as Butler and Morton to its site.

The literary interview -- a long-form Q&A with a creative writer -- has been a mainstay of modern literature, as Rebecca Roach’s new book, Literature and the Rise of the Interview, recounts. Paris Review stamped the genre on the American scene, taking the form from an occasional journalistic sketch to a substantive 20- to 40-page account, and since 1953, it has run more than 400 with writers from Ernest Hemingway to Claudia Rankine. Many other literary journals have followed suit, with more than 190 literary journals carrying them, according to the writer’s guide Newpages.com.

Yet despite the flourishing of the literary interview, curiously there were almost no interviews with critics or scholars in the United States until the 1970s. For instance, Lionel Trilling, who was a major intellectual and whose 1950 book, The Liberal Imagination, a collection of essays on literature, culture and politics, sold almost 200,000 copies in its first two years of publication, never received a full-length interview in a literary or critical journal.

Nor did Edmund Wilson, perhaps the leading American critic from the 1920s through 1960s and the archetype of the public intellectual. That is, except for two mock interviews he himself composed, one called “Every Man His Own Eckermann,” with cheeky comments about authors and his love for yellow pads. It seemed that interviews flirted too much with popular culture, and critics were more serious.

Compare that dearth with the myriad interviews with contemporary critics Edward W. Said, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Cornel West, Slavoj Žižek, Jack Halberstam, Fred Moten, Sianne Ngai, Butler, Morton and many others. Not just short responses, but long-form explanations, which often give serious critical comment, useful overviews and helpful clarifications of their work.

How did this colloquial form make its way into the academic repertoire? And why its current proliferation?

A Conversational Bridge

The interview roots back to Plato’s and other ancient dialogues that present ideas in a fictitious tableau of conversation. It also descends from an 18th- and 19th-century subgenre offering the thoughts and opinions of major writers or artists, such as James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson and Johannes Wolfgang Goethe’s Conversations With Eckermann.

But the interview did not take its more contemporary stance until the late 19th century, when newspapers started using direct quotes from sources and also featured “Visits With the Author,” giving personal glimpses of a writer. In the early 20th century, the film production system made ready use of the form, presenting profiles of movie stars as part of that industry’s promotional machinery. The connection with movie publicity is probably what causes some suspicion of the genre in academic environs.

In 1953, Paris Review included an interview with the esteemed British author E. M. Forster in its inaugural issue. It was not a mere “visit with the author” but presented reflections about his work, his views on literature and his ambivalent assessment of his own novels, at a length equivalent to a standard short story. Paris Review made it a habit thereafter, expanding to two or three interviews in each issue by the 1970s, and spinning off two multivolume book series collecting them, Writers at Work, and, most recently, The Paris Review Interviews.

They did not interview critics, though. In fact, Paris Review started doing interviews as a counter to all the criticism that bloomed amid the expansion of the post-World War II American university. In a famous phrase of the time, the poet and critic Randall Jarrell called it “the age of criticism,” with a variety of active schools, such as the New Criticism, myth criticism, Freudian criticism and even Marxist criticism. Paris Review aimed to counter that: as one of its founding editors, George Plimpton, remarked, “In an Age of Criticism, when so many magazines were devoted to explanations and exegeses of contemporary texts, the notion was to skip the indirect approach and seek out the authors in person to see what they had to say.”

Criticism built up its side of the institutional street, filling the pages of new academic journals such as Modern Fiction Studies and Twentieth-Century Literature. They diverged from the journals that carried creative writing, and they did not do interviews. Criticism was presumably a subordinate service to literature, plus it was relatively accessible in its own right, as the critic tended to speak to an “educated reader” -- an audience bolstered by the increasing numbers of college graduates in the post-World War II era. Surprisingly to our ears, the New York intellectual Irving Howe remarked in the introduction to a 1959 anthology of criticism that, “in some ways [the critic] seemed even more accessible than the poet or novelist.”

The critical interview -- with a critic instead of literary author -- emerged during the 1970s, alongside the new, difficult French theory. One would think that they were strange bedfellows, mixing arcane wine in popular skins, but that combination might have been their strength. The interview entered the scene in the pages of a wave of journals founded through the decade to feature theory, or what I’ve called “the theory journal.” In particular, the journal Diacritics, founded in 1971, ran regular interviews with critics and theorists, as well as creative writers, over its first two decades.

One influence was the Paris Review model, while another was a European model, where there was a more robust tradition of intellectual interviews, in newspapers as well as more cerebral journals, and little distinction between creative writers and critics or theorists. Other influences in the background were history, particularly the emergence of oral history, and ethnography.

The first wave of critical interviews were often occasional, about a book or specific issue, but by the late 1980s and early 1990s, the genre had coalesced, typically providing a substantive account of a critic’s work and thought. Several journals embraced the form, notably Journal of Advanced Composition, under the auspices of Gary Olson; Radical Philosophy, under the editorship of Peter Osborne; and Minnesota Review, under my editorship, which together carried more than 50 interviews through the ’90s.

What prompted this turn? In a recent study, “The Rise of the Critical Interview,” I offer a few explanations. One is that they provided an accessible channel to otherwise inaccessible -- specialized, technical and difficult -- discourse, figuratively and sometimes literally translating what critics were saying into a more colloquial form. Despite complaints about theory at that time and since, they compensated for its distance, building a conversational bridge for scholars across fields and for students wanting to get a hold on the new theory.

Another factor might be a change in cultural taste. Critics at midcentury, like the New York intellectuals and New Critics, averred the high cultural value of literature, whereas subsequent generations have been less preoccupied with the distinction between high and low forms. The sociologists Richard Peterson and Roger Kern adduce that, since the 1980s, the purveyor of culture has morphed from the snob to the “cultural omnivore.” You might have both Mozart and Mac Miller on your playlist, and many things in between.

Similar to the way that contemporary fiction since the 1990s has assimilated what were deemed lower genres, critical writing has assimilated the interview, as well as other modes, like memoir. Particularly in the age of cultural studies, we have become “critical omnivores,” so we might draw on many different bodies of thought, as well as forms that deliver them. You might check out a thinker via an academic article, a YouTube lecture or an interview.

The Ubiquity of the Interview

In the past decade, the critical interview has become even more common. They are an established entry in a number of journals, in their print platforms as well as their new online subsidiaries. For instance, Boundary 2, Public Culture, Social Text and Symploke ran about 50 from 2010 to 2015, a number of them exclusively online. And they crop up in journals such as Diacritics, differences, New Literary History and many others. The article no doubt remains the primary academic form, but interviews might gain more readers per entry, as they tend to speak to a broader audience than most articles, which usually address specific topics and fields.

Yet more prominently, the critical interview has cascaded in various new media venues, formal and informal, in text, audio and video versions. As I mentioned, they are a regular feature in crossover journals like LARB and Public Books, and they form the main content of new ventures such as 3:AM Magazine, which has run hundreds with philosophers and some critics and theorists. Beyond those more formal sites, there have been countless others from publishers, institutions and personal sites. One can also see revived videos of, say, Foucault, interviewed on French television in the 1960s. Indeed, it seems the age of the interview.

This profusion still serves to elucidate theoretical material, but it also answers an increased need in the era of cultural studies and interdisciplinarity: with the seemingly fractal-like multiplication of fields, subfields and innovative intersections of fields, interviews help explain the otherwise disparate tracks of scholarly and critical work. The sociologist Andrew Abbott has pointed to “the chaos of disciplines” in our time, as disciplines expand and add new pursuits to old. Interviews offer a generalist discourse to negotiate the chaos.

In addition, interviews offer one answer to the demand for the public justification of academic work. In presenting more accessible explanations, they fashion a tool for the public humanities. Their grafting with a popular form is not a deficit, in this respect, but perhaps their adaptive strength.

The downside is that sometimes interviews, especially in short form, seem to echo other media promotional systems, serving primarily to sell a book, idea or career rather than to contribute to professional debate and knowledge. That tension has run through the history of the interview. On the one hand, the form flirts with the transitory and superficial, whereas, on the other hand, it forges a colloquial bridge to serious intellectual material.

The rise of new media has clearly spurred the proliferation of interviews: new media encourages short, quickly absorbed material, and the interview’s ready production satisfies new media’s demand for continuous content. New media, however, does not necessarily disrupt the established form of the critical interview, which proceeds apace; rather, the long-form version exists symbiotically with the short take, as does the long-form article.

However, the expanding mediasphere of scholarship and criticism does suggest a shift in the modes and audience expectations of academic writing. Ironically, while postmodern theory claimed to question conventions, it saw the reproduction of the conventional scholarly article -- typically 6,000 to 9,000 words, with paraphernalia like notes or works cited. Now it seems that, alongside the scholarly article, there is a more variegated range of genres, such as the interview, the short response and the 2,000-word essay, not to mention the podcast or YouTube clip.

Rather than its just being a result of new technology, a key factor in the rise of the interview has been the political economy of literary study, its support and its rewards. As the younger critic Nikil Saval, an editor of n+1, observed, “The reward structure of academic life has quite obviously broken down,” leading graduate students to question, “‘Why should I participate in this?’ And they write for the places they want to.” When the large majority of newly minted Ph.D.s cannot attain fully franchised professional positions, then they have less reason to reproduce the forms and norms of the profession that has shortchanged them -- and look to forms that they actually like to read.