You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Shaun Harper

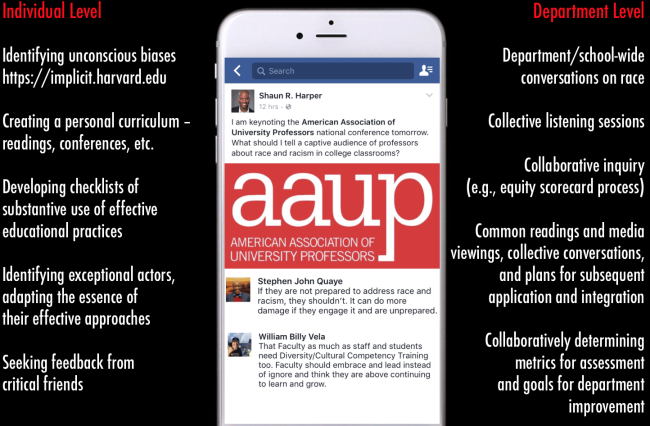

WASHINGTON -- What should faculty members know about talking about race in the classroom? Everything from “everything” and “When you do not interrupt racism in the classroom, you perpetuate it” to “Do better!” and “They’ve already got many of resources they need to do it well.” That’s what Shaun Harper, professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania, said Friday during a keynote address to the American Association of University Professors at its annual meeting here.

More accurately, that’s what Harper’s friends -- mostly fellow faculty members -- offered as advice when he posed that question to them on social media ahead of the conference. Harper originally thought he’d be talking about a chapter from this forthcoming book, Race Matters in College (Johns Hopkins University Press); the publication is based on personal and professional anecdotes as well as on both existing and original research -- much of which stems from his work as founder of the Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education at Penn. Yet Harper said that at the last minute he decided to crowdsource content for his speech to see what was on the minds and hearts of peers in the field.

Turns out, they had a lot to say, and their comments reflected themes expressed in a major subset of race- and diversity-based sessions at this year’s conference. In the wake of an academic year that saw an uptick of campus protests, with some focused on professors and the curriculum, the AAUP included many such sessions this year.

Perhaps one response to Harper’s question was most telling: “That you had to ask your colleagues … this question still in 2016 and you received 54 comments with keen observations and responses, tells us that the issue is alive and well in American higher education … but we are still fighting!”

Harper, a nationally known commentator on race in education, didn’t agree with all of his colleagues’ recommendations, however. “If they are not prepared to address race and racism, they shouldn’t do it,” one comment said, noting that “it can do more damage if they engage it and are unprepared.” While Harper agreed that preparation for talking about race is key, and that a lack of preparation can indeed be harmful, he said it was the duty of all faculty members to get prepared.

Ultimately, Harper said in an interview after his talk, the matter is one of “racial literacy.”

“It’s not necessarily your fault you don’t know how to have this kind of conversation, but it is your responsibility to amass the skills that are necessary for moving forward.”

Harper said during his talk that faculty members should understand that microaggressions are real and harmful in the cumulative. They’re not overt acts of racism, but rather subtle racial digs, such as asking an Asian-American person who says home is Columbus, Ohio, where she’s “really” from. It’s asking a Native American person to speak for all Native Americans, or expressing surprise that an African-American student can “write so well.”

Comparing such microaggressions to paper cuts, Harper said one won’t necessarily affect a student’s overall experience at college, but multiple ones over time will. Harper didn’t argue with research suggesting that retention and graduation rates for underrepresented minority students are lower than the overall average because of various external factors, such as that they are disproportionately first-generation college enrollees. But he said such data aren’t reason to deny that campus climate plays a role, as well.

Somewhat controversially, given that AAUP has been critical of some of the implications of trigger warnings for academic freedom, Harper also endorsed such warnings ahead of potentially upsetting course content. Asking the crowd who had a nut allergy, Harper said that just as it’s helpful and potentially lifesaving to warn people eating lunch ahead of time about what’s in it, trigger warnings make sense in the diverse classroom.

Taking a cue from another colleague’s suggestion, Harper said it’s imperative that faculty members understand the biases with which they enter the classroom -- because everyone has them.

“This necessarily demands that we do some really deep and honest reflective work right now,” Harper said, regarding “the ways in which you might have been inadvertently socialized by parents and family members and messages in the media -- for example, ‘black dudes are dangerous’ -- and the other kinds of things we’ve been socialized to believe about the racial other.”

He said it’s also important to think about where that was “disrupted for you, where was your consciousness raised in your own sort of life journey?”

Harper recalled visiting the campus of an unnamed small college several years ago to speak with students about race; he also often visits campuses to perform climate surveys and offer suggestions for improvement. After his speech, during a question-and-answer period, Harper said an undergraduate asked him, “Why ‘coloreds’ do this and ‘coloreds’ do that.”

Taken aback, Harper said with a wink that he adopted a “loving, educational stance” and offered the student a brief primer on the historical “baggage” attached to that term. Later, the student approached him to apologize, saying it was a word his family used and that he meant no offense. Harper accepted the apology and made small talk, asking the student where he was from and what he was studying. Surprisingly, the student was a senior -- and it was the middle of his final term.

Astoundingly, Harper said, the student was about to leave college without the skills to talk about race and engage people of other backgrounds. Such is the danger of avoiding or neglecting such discussions in college -- and why it’s every faculty member’s responsibility, he said.

Yet while students arguably have some room to make mistakes as they’re gaining such skills, faculty members who may be equally clumsy don’t have the same kind of flexibility, Harper said.

Harper suggested that education was partly to blame, since many graduate students are lucky to take one course on how to teach before they become faculty members themselves -- and that should be a floor on which to build. Yet despite that lack of training, professors must assume responsibility for and close their gaps in knowledge before they can effectively lead class discussions, Harper said. That means seeking out training and even practicing talking about race with colleagues.

Yet in a time of heightened consciousness about race on campus, even prepared faculty members may still be too afraid to engage their students. In a recent case at the University of Kansas, for example, a tenure-track professor who used the N-word in an admittedly clumsy attempt to illustrate this was not the kind of language she heard on campus was not reappointed after students complained about that incident, among others. (The case is complicated. Read about it here.)

Asked about such potential anxieties and that case in particular, Harper said they’re no excuse to stay quiet. Professors “have to learn to engage in and eventually lead these conversations in productive ways. It is a university, after all. People are learning new techniques and theories and methods and new things all the time -- and this has to be part of one’s professional learning and responsibility. There’s a responsibility to become more highly skilled.”

Talking about race in the classroom was the topic of several sessions at AAUP’s conference this year, including one called “Courageous Conversations: Teaching About Human Diversity in the Classroom,” by Katherine Morrison, an associate professor of community health and wellness at Curry College.

Morrison, a competitive public speaker, said that confronting such issues will always stir up emotions, including fear, and she encouraged audience members to write down three or four anxieties the idea evokes -- from dealing with emotionally charged conversations to responding to anger to dealing with different readiness levels and possibly getting negative student evaluations of teaching.

She asked audience members to think about their own identities, racial and otherwise, and then suggested a series of teaching strategies for such conversations. Those include limiting lectures and allowing discussions (but not debates), encouraging a nonjudgmental atmosphere, letting students set ground rules and managing class size, if possible. It’s helpful to make courses heavy in such content reading and writing enhanced. Inviting guest speakers is encouraged, as is giving students “space to admit their prejudices.”

Asked about how much room a professor has for error, Morrison said via email that “there is space in the classroom for clumsiness and error, given the learning environment that you build. I try to build an environment where the students are fully aware that I am fallible. They feel safe enough to engage me in discussions with their own opinions based on their life experience. And that's what I want and nurture because I want to learn.”

At the same time, she said, the Kansas case -- in which multiple students complained about the professor -- seems different. “If we are talking about such sensitive issues, a professor can't believe she can dance between raindrops and talk so disparagingly about race with her limited understanding of the pressures that weigh heavily on the souls of people who have been pushed to the margins of society,” Morrison said.