You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

SHEEO

It’s impossible to examine state higher education finances in 2016 without separating the collapse in Illinois from a more nuanced picture across the rest of the country.

State and local support for higher education in Illinois plunged as the state’s lawmakers and governor were unable to reach a budget agreement and instead passed severely pared-down stopgap funding. Educational appropriations per full-time equivalent student in the state skidded 80 percent year over year, from $10,986 to $2,196. Enrollment in public institutions dropped by 11 percent, or 46,000 students.

That situation proved to be enough of an outlier that it weighed down several key markers in the 2016 State Higher Education Finance report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers association, which is being released today. The report annually offers an in-depth look at the breakdown of state and local funding, tuition revenue, enrollment, and degree completion across public higher education, a sector that enrolls roughly three-quarters of students in U.S. postsecondary education.

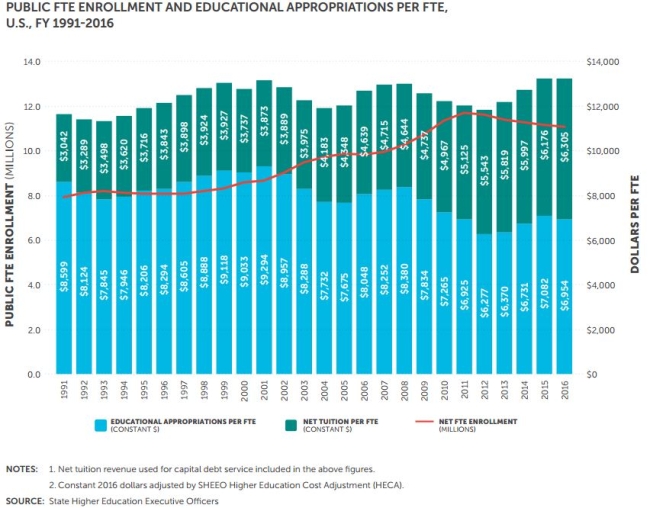

Include Illinois in the report’s key markers, and overall public support for higher education fell by 1.8 percent per full-time equivalent student in 2016, to $6,954, according to the report. Exclude Illinois, and overall support increased by 3.2 percent, to $7,116.

A 3.2 percent increase would have represented the fourth straight year of greater per-student public support for higher education across the country. However, it would not have matched the 5.2 percent increase reported last year.

“Our data is made up of so many different states,” said Sophia Laderman, SHEEO data analyst and the report’s primary author. “Without Illinois, we’re seeing an increase in appropriations per student, after adjusting for inflation. But it’s smaller than in the previous year.”

Breaking down the nationwide average shows significant variation between states, likely driven by localized economic and political conditions. Support for public higher education declined in 17 states in 2016, including Illinois. Support rose in 33 states. Oregon posted the largest increase in a state, of 14.6 percent. Oklahoma posted the largest decrease outside of Illinois, 12.6 percent.

Support fell by more in two other jurisdictions the report incorporates -- it fell by 42 percent in the District of Columbia and 17.6 percent in Puerto Rico.

The year before, in 2015, support fell in only 10 states. It rose in 40. The increase in the number of states cutting support per full-time equivalent indicates they could be dedicating more money to other priorities like health-care costs and pensions. It could also signal more financial pressures for colleges and universities. That in turn could lead to higher tuition at public institutions.

Yet public colleges and universities posted their lowest increase in tuition revenue in years in 2016. Net tuition revenue per full-time equivalent rose by 2.1 percent at public institutions across the country, including Illinois, from $6,176 to $6,305.

“You see some institutions in some states basically have frozen tuition,” said George Pernsteiner, president of SHEEO. “Some have actually rolled it back, but I think most institutions in most states are now much more cognizant of the affordability problems that their students are encountering and much more reluctant to push for big tuition increases.”

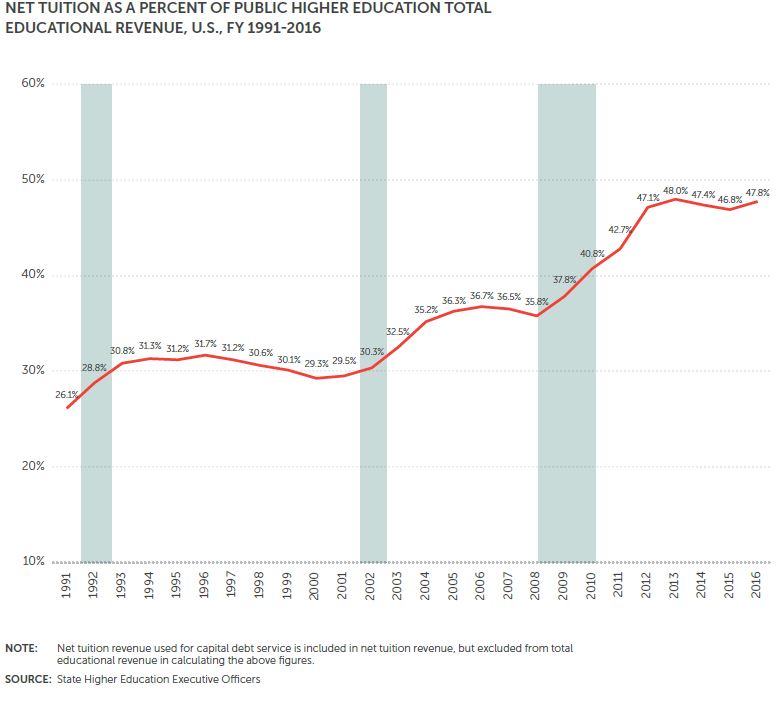

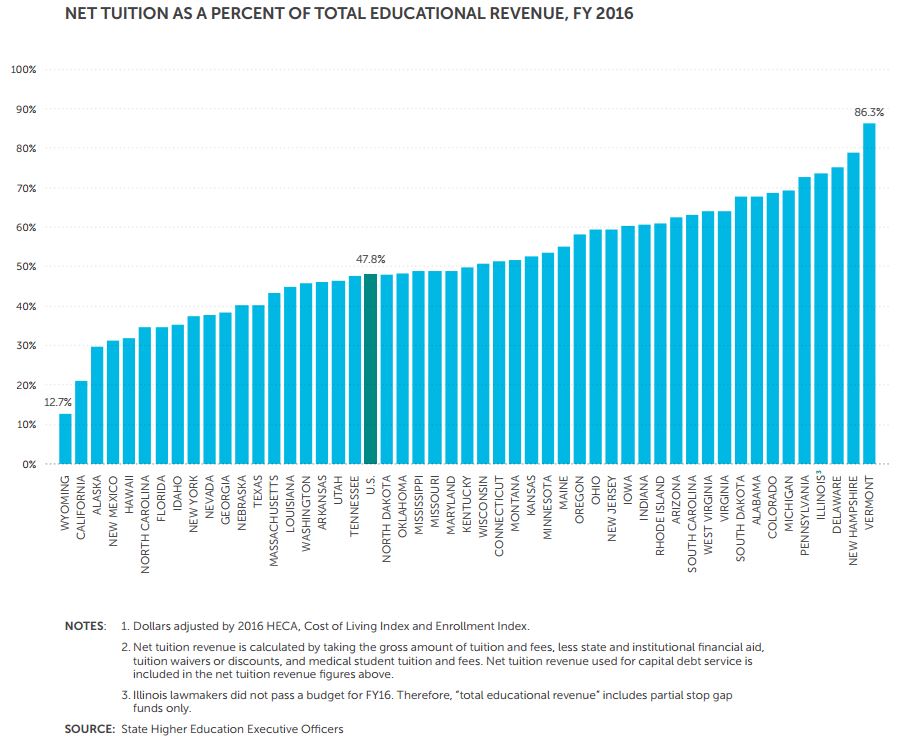

Still, tuition took on increasing importance in public institutions’ budgets. The share of total educational revenue represented by tuition increased to 47.8 percent in 2016, up from 46.8 percent in 2015. It climbed near an all-time high of 48 percent recorded in 2013. Excluding Illinois, tuition income would have been 47.2 percent of educational revenues.

The increasing reliance on tuition is likely due to several factors beyond the situation in Illinois. Notably, enrollment in community colleges has fallen in the years since the recession. That shifted the overall student body to be more heavily enrolled in higher-tuition four-year colleges and universities.

The SHEEO report’s authors noted that more and more states are relying heavily on tuition revenue, though. A handful of large states that heavily subsidize public institutions, like California and New York, pull down the U.S. average for tuition as a percentage of educational revenue. A total of 31 states relied on net tuition for a higher-than-average percentage of total educational revenue in 2016. Just two years ago, only 28 states did so.

A future U.S. recession or economic shock will likely push the country past the point where net tuition accounts for half of U.S. educational revenue, said Andy Carlson, SHEEO principal policy analyst. Many individual states are already past that point, he said.

“Probably during the next official downturn, the U.S. number will hit 50 percent,” Carlson said. “But the reality is that in 25 states we’re already there.”

Recessions typically lead states to cut educational appropriations as their own tax revenues fall. That in turn leaves public colleges and universities more reliant on tuition as a source of revenue.

Looking ahead, several states cut their support for higher education in 2017, according to another report, the Grapevine survey, released earlier this year. Still, that report showed appropriations across all states growing 3.4 percent in 2017.

Over all, state and local governments provided almost $90.5 billion in higher education support in 2016, counting Illinois, according to SHEEO. That’s down slightly from about $91 billion in 2015. It represents the first decline in four years.

Public support has generally yet to recover from a high point in 2008, the year before the Great Recession devastated state budgets. Just five states offered more public support per student in 2016 than in 2008. Institutions are still collecting more dollars per full-time enrollment thanks to higher tuition revenue, however. In 2008, educational appropriations per full-time-equivalent student averaged $8,380, while net tuition was $4,644. In 2016, educational appropriations per student were $6,954 and tuition was $6,305.

States have increased support for student financial aid. State funding for student financial aid programs at public institutions jumped 2 percent, to $7.1 billion, in 2016. That’s up from $5 billion at a previous peak in 2008.

Money dedicated to financial aid has been rising slowly but steadily, according to Pernsteiner, SHEEO’s president.

“I think some states are recognizing that if they do not believe they can afford any longer to support every student, then they’ll support those with the most need,” he said.

Full-time-equivalent enrollment at public institutions fell about 1 percent nationwide, to 11.1 million. It’s the fifth straight year of an enrollment decline after a peak of 11.6 million in 2011. Enrollments rose in the early years of the Great Recession but have been declining since then. Such a pattern is common during and after recessions, as students gravitate toward education when the economy struggles and move back into the job market when it improves.

Degree completion has been on the rise, however. The SHEF report only has degree completion data available through 2015. But it shows that certificate completion rose 3.6 percent between 2014 and 2015 and associate degree completion rose 3.2 percent during that time. Meanwhile, bachelor’s degree completion rose 2 percent, master’s degree completion increased 1.4 percent and doctoral degree completion climbed 1.5 percent. Full-time-equivalent enrollment dipped 1 percent during the time frame.

Over the 10-year window between 2005 and 2015, total certificate and degree completion at public institutions across the country jumped 35.5 percent, to about 2.9 million, according to the report. Enrollment grew more slowly, by just 12.9 percent, to about 11.2 million.

In other words, completions per 100 students rose by 20 percent over the decade, to 26.3.

That’s an important point, according to Pernsteiner.

“It says the institutions are more effective and the students are more focused on earning degrees than they were a decade ago,” he said. “I think part of that is the drumbeat of the economy. Part of that is the focus that states have put on attainment goals. But regardless of why, it is occurring.”

.JPG)