You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Geoffrey Stone, Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor of Law at Chicago, is something of a free speech purist. He chaired the committee that wrote the much-emulated Chicago statement on campus speech, for example, and he’s not afraid to make students uncomfortable if it helps them learn.

Until this week, that included saying the N-word in during a First Amendment law lecture he often gives on the fighting-words doctrine. That’s the legal line between free speech and words that would incite immediate violence or retaliation. Stone has previously argued that saying the N-word to illustrate it is useful.

This week, however, after meeting with a group of students who were hurt by his recent use of the word, Stone said that he won’t say it anymore.

“This is really important -- this is not about censorship, or about anybody telling me what to do or not to do,” he said. “This is something on which students have enlightened me. And that’s great.”

Stone’s been telling the following anecdote from early in his teaching career for years: a black student in one of his classes said the fighting-words doctrine might be outdated. To make a point, a white student in the class then said, “That’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard, you stupid [N-word].” As Stone tells it, the black student immediately lunged at the white student, illustrating that the doctrine was indeed still relevant.

This semester, however, the anecdote didn’t go over as he’d intended. Stone said he was visited by a white student in his class who was deeply offended by his use of the N-word and by a law school student leader who had heard complaints from several black students.

Stone said that he spoke with the two students and heard their concerns. He also explained his rationale for using the slur -- to educate, not to harm students -- at the next meeting of the First Amendment law class.

That’s something of a common distinction for professors to make: using the word because it appears in a text, case law or pertinent example of a concept is acceptable, while using it against a student or any other individual or group is absolutely not.

Increasingly, however, professors are facing complaints from students and, in some cases, colleagues, for using the word in any form. A professor of anthropology at Princeton University, lecturing on hate speech and cultural taboos, gave up teaching a class last year after students faulted him for using the slur in a manner that he believed was educational, for example.

Princeton supported that professor’s right to use the word. That isn’t always the case on all campuses. Augsburg University recently suspended a professor for using the N-word in a class lecture about a James Baldwin novel in which it appeared.

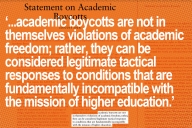

But Chicago supports Stone, saying in a statement that it is “deeply committed to the values of academic freedom and the free expression of ideas, and to fostering a diverse and inclusive climate on campus.”

Universities “have an important role as places where controversial ideas can be proposed, tested and debated by faculty and students,” Chicago said. “Faculty members have broad freedom in the choice of ideas to discuss in the classroom and in their expression of those ideas, and students are free to express their views on those subjects.”

Regardless of institutional responses, many professors have vowed on their own not to use the word at all.

In Stone’s case, he believed the matter was resolved after he clarified for his class why he’d used the slur. But the student who’d originally complained to him went on to publish an op-ed this week in The Chicago Maroon student newspaper about the incident.

A professor “doesn’t have to use the actual N-word to explain to students why that word could incite violence. We already get it,” wrote the student, David Raban. “And any point he tried to make was completely obscured because both his story and act of retelling it were racist.”

Raban added, “They were racist because he, as a white man, repeated a word used by white people to perpetuate the subjugation of black Americans for hundreds of years. He trivialized the word’s history and the lived experience of black students. He employed the word to highlight a white student’s reprehensible treatment of a black student. He lent credence to the false stereotype that black men are prone to violence. He primed black students through stereotype threat to learn less and perform worse.”’

A day after the op-ed appeared, Stone said, he left his office to get lunch and was approached by a group of black law students who asked to talk to him.

In what Stone said was productive exercise of the First Amendment, the students conveyed to him that the N-word was so loaded, hateful and ultimately distracting that using it in class negated any educational benefit.

Stone was persuaded.

“It was very illuminating, I have to say,” he said. “I then went into class and basically said that, having had this conversation with these students -- not because anybody made me do this, just from listening to them about what a distraction it is, and how much pain is caused -- I’ve decided not to use this example in class.”

Stone didn’t want to overstate the significance of this shift. He’s changed his mind about many other things many other times in his career, he said. But it is a shift. Just last year he told Inside Higher Ed that it is “perfectly appropriate to use such language in the classroom if the word is relevant to the material or issues being discussed.”

A literature professor teaching Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, a history professor teaching about racism or a law professor teaching a case involving the use of such language can “and in my view should use the word if using it is relevant to what is being taught,” he added at the time.

In 2017, he also publicly defended his use of the N-word in a lecture at Brown University, after a student present told him it had a chilling effect on the conversation.

Stone isn't sure how he'll talk about slurs in his class going forward, when necessary. He doesn't like to say "N-word" when it's clear the relevant content pertains to the actual word, he said. But he's confident he'll figure it out.

Things change, Stone said. Ten or 15 years ago, students probably wouldn’t have reacted to the word the way they do now, he added, saying he wished offended students had approached him sooner to express their views. Stone also said he has two small grandchildren who are black, and who he hopes won't be made to feel the way the group of students said they did, when they someday attend university.

“That’s why this a great example of free speech, which means not only talking, but also listening,” he said.