You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

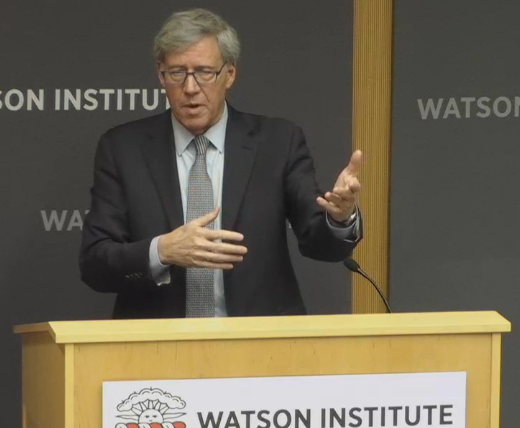

Geoffrey Stone

Brown University

Campus speech debates have become heated, and even violent, in recent years. What happened at Brown University recently isn’t one of those incidents. Instead of protests, a visiting speaker -- and his controversial comments, including the N-word -- prompted discussion.

Geoffrey R. Stone, the Edward H. Levi Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, was at Brown this month as part of the campus’s “Reaffirming University Values: Campus Dialogue and Discourse” program. Richard M. Locke, Brown’s provost, introduced the series of lectures and workshops last semester as a way to “consider how to cultivate an environment in which we, as a community, can discuss conflicting values and controversial issues in constructive and engaging ways.”

The role of “dialogue on campuses and in public life more broadly has become of increasing concern in recent years,” Locke said in a letter to the campus. “The ways in which we talk across difference have become as important as the substance of the issues we discuss, especially the divisive ones.”

Like a number of other institutions, Brown has seen student unrest over on-campus race relations since students at the University of Missouri at Columbia staged protests on their campus in 2015. While it wasn’t seen as a national hotbed of such protests, as a famously liberal university, Brown still was taking something of a risk in attempting to tackle today's campus speech issues head-on.

Locke described the worthiness of the cause like this: “At the core of these efforts is a robust recognition of our fundamental commitment, as an institution of higher education, to learning -- on the part of students, faculty and staff. Our success in these endeavors rests on the commitment of members of our community to this approach.”

Conversations about serious issues are “too often characterized as polarizing, and occur in a highly charged, rancorous atmosphere where speakers often anticipate being criticized, ridiculed or ‘called out.’ Those who are uncertain or uncomfortable often remain silent or are reluctant to engage,” he added. “We must work to empower all individuals to share their viewpoints, even if it makes some of us, at times, feel uncomfortable. Creating an environment in which productive dialogue occurs is essential for our university."

Stone, a First Amendment scholar and former provost at Chicago who chaired its Committee on Freedom of Expression, delivered a speech at Brown called “Free Speech on Campus: A Challenge of Our Times.” He began with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s dissent to a 1919 decision, Abrams v. U.S., in which the court upheld a ruling against a group of young Communists who opposed American involvement in World War I.

Holmes, Stone said, “warned, ‘We should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression’ even of ‘opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten’ compelling government interests that an immediate check is necessary to save the nation.”

Stone said the passage had animated his career, and said that it’s “important to understand that, like the freedom of speech, academic freedom is not a law of nature. It does not exist of its own force. It is always vulnerable, and should never be taken for granted.”

Indeed, he said, academic freedom didn’t really exist for much of the 19th century, and that any “student or faculty member who dared argue, for example, that women were equal to men, that blacks were equal to whites, or that homosexuality was not immoral would surely [have been] expelled or fired without hesitation.”

Similar issues arose again during the more recent McCarthy era, he added, proving that “academic freedom is, in fact, a hard-bought acquisition in an endless struggle to preserve the right of each individual, student and faculty alike, to seek wisdom, knowledge and truth, free of the censor’s sword.”

What does that have to do with today’s students? Stone said that anyone who benefits from academic freedom has an obligation to it, namely by defending it “when it comes under attack” and by struggling “to define the meaning of academic freedom in our time.” As seen in the Abrams case, he added, “the Constitution's guarantee of freedom of speech is not self-defining. Neither is academic freedom. Each generation must give life to this concept in the face of the distinctive conflicts that arise over time.”

Stone listed recent free speech flare-ups at colleges and universities, some of which involved student demands for censorship. Those include revocations of invitations to speakers on a number of campuses, calls for Vanderbilt University to fire a tenured professor for writing publicly about her highly critical views on Islam, and requests that Amherst College remove posters saying “All Lives Matter.”

Cautioning against censorship, Stone encouraged students to “always be open to challenge and question." He warned them that censorship was a two-way street that could eventually be used against them and said suppression of speech chills speech.

While colleges and universities should promote civility and mutual respect, and support students who feel vulnerable, he continued, “The neutral principle of no suppression of ideas protects us all. This is especially important in the current situation, for in the long run it is likely to be minorities, whether religious minorities, racial minorities or political minorities, who are most likely to be silenced once censorship is deemed acceptable.”

Controversial Q&A

While Stone could be described as a free speech “purist,” his views are very much in line with those of other First Amendment scholars, and his prepared remarks proved uncontroversial, even at Brown. During a lengthy question and answer period, however, he was asked by Martha Nussbaum, Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at Chicago, who was also at Brown, about a professor's role in cultivating a civil classroom space.

Stone responded that the "real issue with civility is, What are the bounds of civility?" For both students and faculty members, he said, classrooms are "narrowly defined professional settings" that don't warrant expectations of full free expression. The use of epithets, for example, he said, "is perfectly appropriate if relevant to the material, but inappropriate if a faculty member calls a student a kike, or if a student calls another student a nigger. I would say that's crossing a boundary."

Stone said he'd only ever encountered slurs in the classroom once, 35 years ago, when he was teaching the "fighting words" doctrine, or the notion that some speech is not protected when it could provoke violence. A black student in his class commented that such restrictions are outdated and unnecessary, Stone said, and another student responded, “You nigger, that’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” The first student promptly reached over to the second to grab him by the neck -- suggesting that the doctrine may not be so old-fashioned after all.

Several questions later, a black undergraduate student told Stone, “I wanted to thank you for your charge to boldness, and, in that spirit, would also like to respectfully request that you refrain from openly using racial epithets in public spaces. I understand you’re not representing an administration right now, but certainly that has a chilling effect on speech for people in the room.” She argued that slurs can be easily alluded to without being said outright.

In response, Stone said, “I teach, among other things, the First Amendment. There are cases that involve these words. You can’t talk about the words in the class when you’re discussing whether the word should be legal or not? Doesn’t make any sense. Or you read it in a novel that uses the words and you can’t use the words? Sorry. But I do hear you.”

The student then asked whether civil discourse was about tone or substance, saying she found Stone's slurs "deeply uncivil."

Stone responded, “Someone who goes around yelling and screaming epithets, even outside the classroom, in a public setting, I would say is being a jackass -- can I say that? Is that OK? Just want to make sure.” He again asked if it was OK to curse when talking about the 1971 Supreme Court case Cohen v. California, about a Vietnam War protester's right to wear a jacket saying "Fuck the Draft."

The student could not immediately be reached for comment, but the student newspaper, The Brown Daily Herald, reported that “many attendees” said they were “uncomfortable with Stone’s response" to her question, in that it was "rude" or compared profanity to slurs. Yet the lecture was otherwise uneventful.

Stone said in a phone interview that his intention was never to “mock” the student, but rather to drive home the underlying point of his speech: “When you legitimate censorship, you’re putting yourself in a very vulnerable position. … Do you really want people deciding which words you can and can’t use?”

Still, Stone underscored the importance of civility and respect, and advised against the “unnecessarily gratuitous and inflammatory” use of racial epithets. “There are educational and cultural values that people should respect,” he said, adding that it would be wholly inappropriate for him to call a student a slur, for example.

A talk on free speech and academic freedom doesn’t meet that bar, though, he said. Despite what's been happening elsewhere, to other scholars, the incident at Brown was in fact the first time a student expressed offense at Stone's use of language, he added. "I've actually been kind of disappointed that students in the audience haven't been more challenging."

On the other hand, as recently as five years ago, Stone's remarks -- prepared and off-the-cuff -- would have been unremarkable in an academic setting, he said. "What makes this moment unusual is that it's students who are demanding censorship, when historically they've opposed censorship."

Christina Paxson, Brown’s president, introduced Stone prior to his talk. In emailed statement, she said, “The student asking her questions reflected exactly the type of open expression we are cultivating at Brown.”

John Wilson, an independent scholar of academic freedom and co-editor of the American Association of University Professors’ “Academe” blog, disagreed with Stone, saying, “It's possible to talk about slurs without using slurs,” and that he usually chooses not to use them. Stone could have said the N-word, with everyone understanding his meaning, for example.

But the “point of a free society is that it's a choice,” Wilson added. “People are free to ask that people not use slurs, and people are free to disagree and use them. I don't see a request as a form of censorship. There's a vast difference between a discussion about what's appropriate and a demand for censorship.”

And clearly, he said, “this is a context -- talking about offensive language -- where the use of slurs is often appropriate.”