Free Download

While college and university business officers are still surprisingly upbeat about their institutions’ financial health and the viability of their institutions’ business models, they are taking steps to alter these models -- cutting in some areas and seeking new revenues in others -- in a way that reflects a more privatized and market-oriented approach than before.

That is one way to interpret Inside Higher Ed’s second Survey of College and University Business Officers, released today in advance of this weekend’s annual meeting of the National Association of College and University Business Officers in National Harbor, Md. (A PDF copy of the report can be downloaded here; the text of the survey report can be viewed here.)

In responding to the survey, business administrators expressed a clear concern about pricing, with about 70 percent of survey respondents saying that increasing net tuition revenue -- the actual amount they derive per enrolled student after factoring in institutional financial aid -- was an important strategy for raising revenue in the near term (more than chose any other strategy). On top of that, online education, collaboration with other campuses, streamlining administrative positions or reorganizing administrative units, and eliminating underperforming programs were, in aggregate across all types of institutions, the strategies in which CFOs were most likely to report that their institutions were engaging.

All of those responses indicate that the business side of colleges and universities is becoming more concerned about which programs generate revenue and which programs and expenses can be culled to maximize that return.

Learn More About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's editors and campus business officers

discussed the survey's results

during a webinar on Aug. 29. A recording of the event can be viewed here.

“More cost-effective delivery, more online learning, increased sensitivity to pricing, greater assessment of underperformance in academic departments. Decisions are being driven ultimately by this question of ‘Where are we getting the most return on investment while maintaining quality?’ ” said Rick Staisloff, principal at RPK Group, a finance consultant for colleges and universities. “We are increasingly moving toward a private funding model in higher education across all sectors.” Staisloff said this is a good shift for institutions, since it recognizes a changing market for students and a need to seek tuition revenue as other sources decrease.

The online survey, conducted in May and June 2012, was completed by a total of 502 campus and system chief business and financial officers. Only nine business officers from for-profit institutions completed the survey, so their responses were not explored in depth.

Other key findings of the survey include:

- Financial officers at private colleges and universities were more likely to be optimistic about their financial position than were their counterparts at public institutions, and business officers at doctoral institutions were more likely to be optimistic than were their counterparts at non-doctoral institutions.

- Respondents were most likely to cite non-flagship public universities (35.3 percent) and non-elite private four-year institutions (39.4 percent) as the institutions whose business models are “unsustainable and must change.” Elite private universities and liberal arts colleges were the institutions most likely to be seen as “viable and sustainable.”

- Provosts and business officers see the budget actions taken in recent years in fundamentally different lights, with provosts more negative about them and business officers more positive, a disconnect that many observers say could ultimately undermine these institutions’ ability to make major changes to their academic programs.

Rose-Colored Glasses

Despite the various headlines announcing that technology will disrupt higher education, that the financial model is broken and needs an overhaul, and that there is a bubble about to burst in the higher education world, college and university business officers who responded to the survey offered a rather upbeat picture of their institutions' finances.

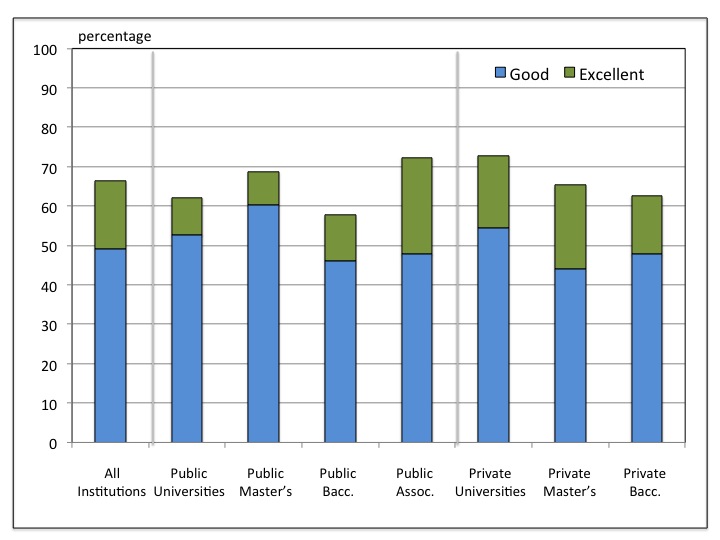

Half of the business officers surveyed said their college was in “good” financial health, with another 17 percent saying their institutions were in “excellent” financial health. Only a third of all respondents gave their institutions’ financial health a “C” or “D” grade, and none said they were failing.

While it shouldn’t come as a surprise that private doctoral universities say they’re in a strong financial position, with 73 percent saying they were in “good” or “excellent” health, community colleges, which many observers say have been hardest hit by state spending reductions, were just as likely to say they were in a strong financial position.

Almost 40 percent of institutions said they were in a better financial position than they were in 2008 -- before the recession -- while only 16 percent said they were in a worse position.

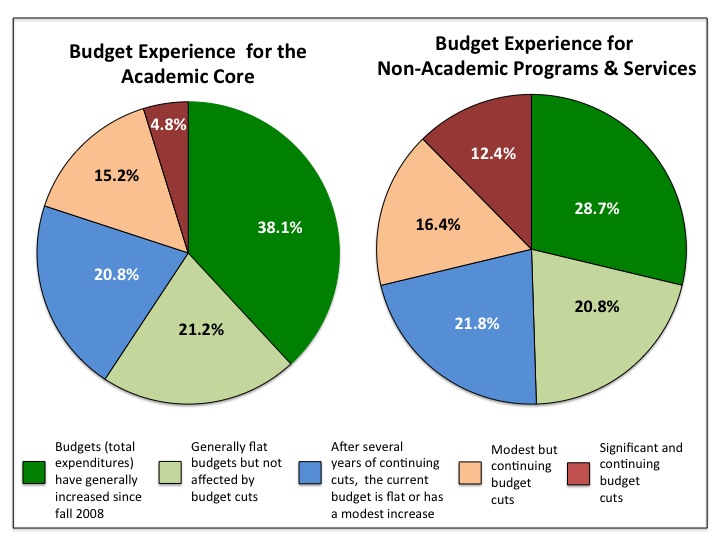

Despite the rhetoric coming out of higher education these days about cuts to academic services and growth in expenses for administrative services, respondents said academic budgets fared better over the past four years than the administrative side of their campuses did. About 38 percent of respondents said their overall expenditures on academics had increased since 2008, with another 21 percent saying budgets for those areas were flat over the same time period.

On the administrative side, about half of respondents said their nonacademic program and service budgets had several years of cuts that had leveled out, or are continuing to experience modest to significant cuts.

While significant questions have been raised about the business models of college and universities, the majority of chief financial officers view the business models of most sectors as either viable or strained but still workable.

They were most optimistic about elite institutions, with more than 70 percent of respondents saying the business models of elite private universities with endowments greater than $1 billion and elite private liberal arts colleges with endowments greater than $500 million were viable. Community colleges were also overwhelmingly seen as having a viable business model, but more respondents said they were strained in the recent economy.

Aside from community colleges, other non-elite institutions were the groups most likely to be perceived as unsustainable and in need of change. About 40 percent of respondents said non-elite private universities needed fundamental change, and 35 percent of respondents said the same for non-flagship public universities.

Almost 60 percent of survey respondents said their own institution's business model was sustainable.

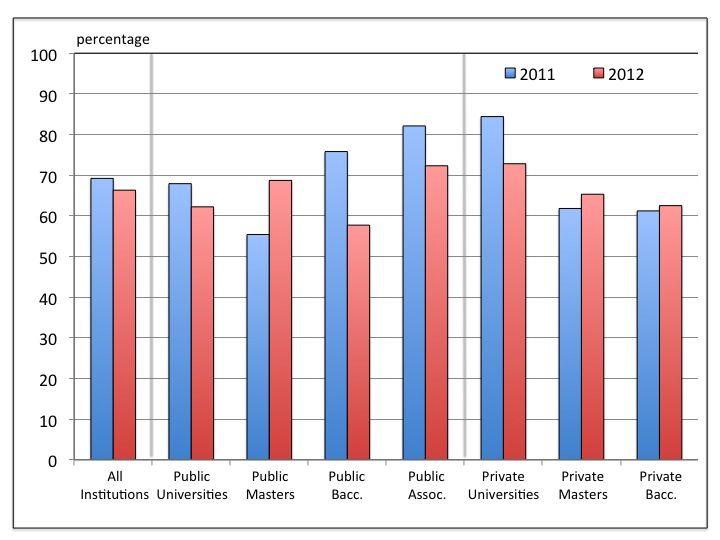

While the general response was positive, the overall proportion of chief financial and business officers who reported their institutions were in "good" or "excellent" financial health dropped slightly since last year's survey. Last year, 69 percent of business officers were positive about their institutions' financial health. That number dropped to 66 percent this year.

Drops were more precipitous in some specific sectors, particularly public baccalaureate colleges, where the percentage reporting solid financial health dropped from 76 percent to 58 percent. Community colleges, private universities, and public universities also saw drops of about 10 percent.

Several individuals who work with university finance officers said they were surprised and puzzled by the positivity of the responses. “There’s more optimism around the current business model than I think is warranted,” Staisloff said.

Kent John Chabotar, president of Guilford College and the former chief financial officer at Bowdoin College, said he was surprised by the number of institutions -- particularly private nonprofit ones – whose business officers said they were in good financial health. “Endowments may have recovered but enrollment, state support, unemployment, and tuition discounting have not,” he said.

Chabotar said that when he speaks to vice presidents, deans, and financial directors, they overwhelmingly say that their financial positions have become worse over the past year.

“Having been a CFO, my guess is that part of this optimism is that the CFOs believe that finances reflect their own performance just like a win-loss record for a basketball coach,” Chabotar said. “The reality is that although the CFO plays a vital role, financial health also depends on a variety of factors outside the business office.”

Observers worried that this belief that the models are sound but just strained will prevent business officers from pushing fundamental changes their institutions that could be necessary in the face of what they see as a new, more competitive market for students and research dollars. "If CFOs have this attitude that if we get through this period we’ll be fine, that means it’s not creating the sense of urgency that I think this change warrants," Staisloff said.

John R. Curry, a managing director at Huron Consulting Group and a former chief financial officer at several universities, said it is unlikely that the level of state support for public universities will return to anywhere close to what it was 10 years ago. He said too many issues -- growing pension and Medicaid spending, backlogged infrastructure projects, and an anemic economic recovery -- all mean states won't have the money to invest in higher education.

Worried About the Right Issues?

Several observers said the upbeat assessment of the market coincides with too little concern about long-term fiscal issues that are threatening the sustainability of many colleges and universities -- particularly health care and retirement liabilities and deferred maintenance.

While close to 60 percent of respondents cited tuition as an issue to which they were paying more attention now than they were five years ago, long-term but potentially costly issues did not register as highly. Deferred maintenance seemed to be a concern for only 40 percent of business officers, health care liabilities for only 35 percent, and retirement liabilities only about 30 percent.

"All the data you look at says health care and pensions are the biggest drivers of spending in institutions, they're going up faster than anything else," said Jane Wellman, executive director of the National Association of System Heads and former executive director of the Delta Project on Postsecondary Costs, Productivity and Accountability. "Why that would be so far down the list?"

About the Survey

The 2012 Inside Higher Ed

Survey of College and University Business Officers is the latest in a series of surveys of senior campus officials about key, time-sensitive issues in higher education.

Inside Higher Ed collaborated

on this project with Kenneth

C. Green, founding director

of the Campus Computing Project.

The Inside Higher Ed survey

of business officers was made possible in part by the generous financial support of ARAMARK, Ellucian, Inceptia and TIAA-CREF.

All decisions about the nature

and wording of the surveys

and all editorial content were made by Inside Higher Ed.

Along the same lines, Curry also said there was not enough emphasis on deferred maintenance. “Nobody thinks about deferred maintenance for next year,” he said. “And in the end it gets you.”

He said the emphasis on short-term problems at the expense of long-term issues is probably brought on by the continuing, pressing financial struggles facing most institutions, particularly at public colleges and universities. “It seems like business officers are focused on the fairly short term, what’s going to have the most immediate impact on them,” Curry said. “Five years seems a long time away in a very volatile world.”

Wellman said the lack of focus on long-term issues might reflect a historic notion in higher education that chief business officers should be focused on maintaining a balanced budget year in and year out, and that long-term issues should be left to others in the institution, such as the governing board and the president. "Their frame of reference might just be year to year, rather than long-term," she said. It might also help explain why these officials say their business models work well despite so many assessments that they are not sustainable.

Becoming Market Oriented

Despite the upbeat assessment of their institutions' health, the rest of the survey indicates that colleges and universities are making fundamental changes to orient their institutions to student demand.

Concerns about rising tuition prices and increasing student loan debt have become national issues, including seeping into the presidential race. A recent survey by Sallie Mae found that over the past two years the average amount families spent on higher education dropped 13 percent, the first two years of decreased spending in the company’s data. "American families reported taking more cost-saving measures and more families report making their college decisions based on the cost they can afford to pay," the report stated.

When asked what issues they were paying more attention to now than they were five years ago, tuition concerns topped the list. Almost 60 percent of chief business officers said they were paying more attention to “market limits on our ability to raise fees,” with private master's and baccalaureate institutions being the most concerned. Almost half of all respondents said the rising discount rate on their tuition was a chief concern, again with private master's and baccalaureate institutions topping the list.

Despite the concern about running into a market limit on tuition, 70 percent of institutions reported that they were focused on increasing net tuition as a way to increase revenues, more than cited any other strategy. Recruiting out-of-state students, who often bring with them more tuition revenue, was a top priority for public institutions. About three-fourths of public doctoral universities and 60 percent of public master's institutions said recruiting more out-of-state students was an important strategy over the next two to three years.

Developing and expanding online programs, securing corporate grants, and growing the size of the endowment all were viewed by more than half of respondents as important strategies.

Revenue strategies seemed much more appealing than did cost-cutting measures. Eliminating low-enrollment academic programs, a move that has been controversial in recent years, was the only cost-cutting approach that at least half of survey respondents said would be an important strategy for them over the next two or three years. Making more effective use of facilities (44 percent of respondents), using technology to evaluate programs and identify potential improvements (41 percent), and using technology to reduce instructional costs (39 percent) also ranked high as cost-cutting measures.

Among the larger institutions such as public and private doctoral universities, centralizing and consolidating administrative functions (62 percent at public, 43 percent at private) and IT resources and services (47 percent at public, 33 percent at private) also ranked high as cost-cutting measures.

Respondents also indicated an interest in using online-education technology to help reduce costs. About 65 percent of respondents said "moving away from our classroom-based model of instruction, shifting more classes online" was something that their institutions were discussing. Similarly, "exploring new collaboration opportunities for academic programs with other institutions" also ranked highly, with 63 percent of respondents saying they were discussing such partnerships.

This focus on using Internet technologies to drive down costs worried some observers, who raised questions about the quality of such efforts and the viability of moving into that market, particularly as several elite institutions have started offering classes free online.

A Tale of Two Sectors

The responses to several questions asked in the survey show a significant difference in the experience of public and private universities on financial matters over the past four years, leaving the institutions in dramatically different positions.

A report by the National Research Council last month noted that the growing disparity between public and private doctoral universities was a significant problem for higher education and the country as a whole, since public universities perform the majority of federally funded research and educate the majority of doctoral students.

Forty-five percent of private institutions said they were in a better position now than they were four years ago, while only 11 percent said they were worse off. Among private doctoral universities, almost 60 percent said they were in a better position in 2012 than they were in 2008, while only 13.6 percent said they were in a worse position.

“The reasonably endowed private doctoral universities have recovered a significant amount of their endowment losses,” Curry said. “In the meantime, they’ve done a lot to wean out their budgets, and they’ve gotten their costs down relative to where they would have been otherwise.”

Private institutions were also much more optimistic about the next three years. While only about 18 percent of public colleges and universities thought they would be better off in 2015, 42 percent of private institutions thought they would be better off.

A House Divided

There was a significant discrepancy between how provosts, surveyed by Inside Higher Ed in December 2011, and chief business officers viewed their institutional health. Business officers were far likelier to say that institutional expenditures on academic programs increased since 2008, while provosts were more likely to report that their institutions “suffered significant and continuing budget cuts to our core academic programs” over the past four years.

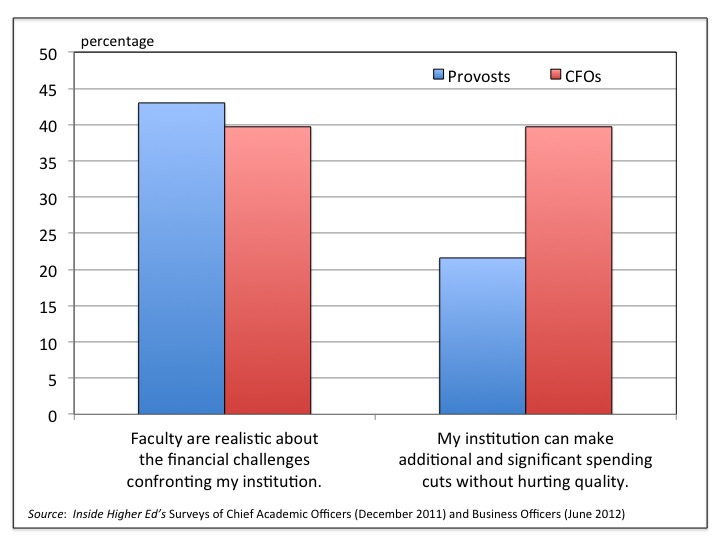

CFOs were also more likely than provosts to say that their institutions could make additional and significant spending cuts without hurting quality (22 percent of provosts, 40 percent of CFOs).

Several survey respondents expressed frustration about trying to control costs in their institutions' academic programs. When asked what campus strategies should be on the table but weren't, large numbers of business officers said increasing teaching loads (43 percent), eliminating underperforming academic programs (41 percent), and revising tenure policies (41 percent).

Other business officers reported more success in these areas, with 51 percent of respondents saying that eliminating underperforming academic programs was under discussion on their campus. Numbers were relatively consistent across sectors and institution types, meaning that tackling that issue might have more to do with institutional culture than with institution type.

Outsourcing academic programs was deemed "appropriately off the table" by half of survey respondents.

Observers view the divide as a potential major impediment to colleges' and universities' ability to retool their academic programs in a way that balances the budget. “That relationship is so critical, so it’s sort of troubling to see those disconnects,” Staisloff said. “You want your provost to be thinking like a CFO and you need your CFO to be thinking like a provost.”

One area where provosts and business officers were more in agreement was whether faculty were realistic about the challenges facing their institutions. Roughly 40 percent of both campus said faculty were not being realistic.

That might be partly attributable to a lack of understanding of financial issues. Seventy-one percent of business officers said greater transparency in the decision-making process would result in better financial decisions. Eighty percent of respondents said senior administrators, who are likely aware of the same data as the business officers, were realistic about the challenges facing their institutions.