You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

St. Edward’s University in Texas could face censure by the American Association of University Professors, based on an AAUP report out today saying that the institution found ways to quickly get rid of three outspoken faculty members -- two of them tenured.

Beyond violating the basic tenets of academic freedom, tenure and due process in these three cases, AAUP’s investigating committee found that St. Edward’s has a generally “abysmal” climate for academic freedom and shared governance. St. Edward’s “heavy-handedness” has created “widespread fear and demoralization among the faculty,” the report reads.

The university said in a statement Wednesday that it has “a robust commitment to tenure and academic freedom” and values “our strong faculty leaders who form an essential part of shared governance at the university.” So the AAUP report “maligns the great work of almost 500 faculty members and imposes its own agenda on our university.”

George Martin, St. Edward’s president, called an earlier version of the report “disappointing” in a Facebook post. He reportedly declined to meet with AAUP investigators when they visited campus in August, saying personnel matters are private and that the university and the association have different standards.

Indeed, St. Edward’s Faculty Manual is relatively “silent,” to borrow AAUP’s term, on procedures for faculty dismissals. Instead, the manual says that professors who are summarily dismissed have the right to a later appeal. But AAUP, which advocates a professor’s right to appeal disciplinary decisions before an elected faculty body, says that is no substitute for due process prior to dismissal.

A Couple of ‘Squeaky Wheels’

According to AAUP, Shannan Butler and Corinne Weisgerber, both associate professors of communication in good standing with about 12 years each on campus, and a married couple, were summoned to a meeting with administrators in January. They were immediately handed dismissal letters citing their “continued disrespect and disregard for the mission and goals of the university.” That’s a fireable offense, according to university policy, but Butler and Weisgerber say they’ve never been given specific examples of how they flouted St. Edward’s mission.

The letters did cite a department meeting a month earlier, in which the professors allegedly treated their colleagues “in an unprofessional, intimidating, and bullying way.” Weisgerber’s letter, in particular, said that “toward the end of what had initially been a productive meeting, you began to question the future of the department, a topic that was not on the agenda.” The professors were asked to return to the agenda, but things got “out of control,” the letter said, as Butler and Weisgerber “persisted in attempting to intimidate” both their interim chair and the previous interim chair.

Butler’s letter said that he also “repeatedly referred” to his membership on the Faculty Evaluation Committee in a way that implied he “would or could use” that role “for personal retribution.” Such an implication is “entirely improper and undermines the integrity of the faculty review process,” it said.

The termination letters also asserted that department members who left the meeting heard shouting -- proof of Butler and Weisgerber’s “unwillingness” to “to engage colleagues in a productive manner.” As proof of a pattern of similar misbehavior, the letters also said that the professors in 2016 “launched an attack” on the decision to appoint someone other than Butler as interim department chair. Short on details, the letters said that the attack included “efforts which constituted harassment, bullying and attempts at intimidation.”

A dean met with the professors in 2016 to address such concerns, and notes about their “disruptive and unprofessional behavior” were placed in their personnel files in 2017. But Butler and Weisgerber continued to behave unprofessionally, including at a later 2017 faculty meeting, according to the termination letters.

Reeling from the news of their immediate dismissals, Butler and Weisgerber were escorted off campus by a security guard. They were given the option to appeal, but banned from campus.

Both professors appealed on several grounds, including that they hadn’t been given a two-year performance improvement plan (or even a single negative performance review) as required by the university’s posttenure review policy with regard to revoking tenure. They also said they’d been denied specific examples as to what constituted “bullying” behavior, and that they hadn’t been formally notified that new disciplinary notes had been placed in their personnel files, in 2017.

But instead of a duly appointed faculty committee, an ad hoc review panel, whose members they never saw or knew the names of, assessed their cases and sided with the university.

An Inconvenient Professor

As shocking as the terminations were, there was something of a precedent, in AAUP’s telling: just a month earlier, Katie Peterson, an assistant professor of reading in her fifth year of service at St. Edward's, received a non-reappointment letter. It didn’t cite her behavior, but rather the university’s attempts to “right size” itself. Peterson got six months’ notice -- more than Butler and Weisgerber got, but not the typical year for professors elsewhere.

AAUP’s report implies that these events are linked in that Peterson also spoke out on issues of concern to her: Peterson told the association that her time on campus had been difficult since at least 2015, when she filed a complaint against an associate dean who made what she called “weird pseudo-sexual comments.” The dean continued to make her uncomfortable until he left last academic year, she said, prompting her to file additional complaints. The new dean then made unspecified comments that “led her to believe that the dean perceived her as a troublemaker and therefore a candidate for nonrenewal,” the AAUP report says.

Peterson further believes she was targeted for personal reasons, not academic or financial ones, because full-time faculty members got modest raises last year, enrollment in her courses was good and the courses she normally taught were assigned to others this year.

AAUP says that under its widely followed recommended policies and procedures, a tenure-track professor notified of nonrenewal in the fifth year of appointment is entitled to written reasons for the decision, the opportunity to appeal the decision to an elected faculty body and at least a year of notice.

Regarding the tenured faculty members, Martin reportedly told AAUP via email prior to the investigators’ visit that its dismissal policy was proposed by the St. Edward’s faculty, approved by the university’s Board of Trustees and included in the university’s Faculty Manual in 1989. The process is fair, he said, includes an independent review by a faculty committee and honors academic freedom.

AAUP disagreed, citing its own widely followed policies, and asked about academic freedom when it visited campus. One person quoted but not identified in the AAUP report described Butler and Weisgerber as “squeaky wheels -- first in line to complain when things are bad.” But “that’s no reason to get rid of faculty, especially tenured faculty,” the person said.

Considering similar comments from other interviewees and the additional evidence, AAUP’s investigating committee concluded that “what the administration deemed ‘misconduct’ on the part of Butler and Weisgerber was nothing more than persistent and conscientious questioning of administrative decisions,” with “university” being used as a stand-in for administration. The language in their dismissal letters was “revelatory,” the report says.

Climate Control

Other faculty members described an overall climate of fear. One longtime professor reportedly said at the beginning of an interview, “I was scared to come here today. When I got out of the car in the parking lot, I literally looked over my shoulders to see who might see me.” Peterson told investigators, “People are angry about what happened. People came up to me all spring and they were angry. And they said, ‘Message received.’” And another longtime professor said, “I have been shocked at the actual, real fear that has been manifested even by long-standing faculty over the last five years.”

Regarding shared governance, faculty interviewees reported that it was very weak, and that questions for the president’s annual visit with the faculty must be submitted and approved in advance. (A spokesperson denied that this week.)

St. Edward’s, “like so many other small institutions, has seen a great deal of structural and cultural change over a relatively short period of time,” the committee concluded. “Equally clear was that much of the change has been driven by the administration and that a large segment of the faculty feels that its voice has not mattered.”

The administration’s recent actions against three “respected and dedicated faculty members have only made the relationship between the administration and the faculty significantly worse,” the committee wrote, “for they further alienated the faculty from the institution so many of them told the committee they ‘used to love.’ As one faculty member lamented, ‘This place has lost its soul, and I feel like I’m losing mine.’”

St. Edward’s in its statement said the AAUP “attempts to take personnel matters and incorrectly recast them as issues of academic freedom.” In all three personnel cases, it said, “the university followed processes outlined in the faculty manual -- processes proposed and approved by the Faculty Senate and approved by the university’s Board of Trustees. We reject the AAUP report and remain grateful for the support and work of our outstanding faculty, who are deeply committed to student success and to our mission and values.”

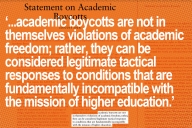

AAUP findings of violations of academic freedom and tenure mean make institutions eligible for censure votes at the association’s annual meeting, typically in June. Censure is symbolic, but most institutions eventually work with the group to remove themselves from AAUP’s censure list to improve their reputations and ability to attract faculty candidates.

Greg Scholtz, director of academic freedom, tenure and governance for the AAUP, said that the St. Edward’s case is notable in that Butler and Weisgerber, a married couple, were treated almost interchangeably, or as a single unit in their dismissals, and that they appear to have been punished for exercising their academic freedom via participating in institutional governance. Echoing language in the report, Scholtz said, “I thought that the dismissal letter they received was unintentionally revelatory in that it seemed to equate a lack of respect for administrative decisions with misconduct.”

Also unusual is the “execrably deficient dismissal policy that made it so easy for the administration to rid itself of these two perceived troublemakers,” Scholtz added. “Most reputable four-year institutions have stronger dismissal policies. This one allowed the administration to send them packing unceremoniously without any warning.”

The appeals process afforded them was not a faculty hearing in which the burden of proof was on the administration, he said, but one in which they had to prove to a “secret committee” that the administration should not have dismissed them.

Violations of academic freedom link all three cases in that Butler and Weisgerber “questioned administrative decisions affecting their department and its chair,” while Peterson had complained of sexual harassment "to an extent that she claimed her dean seemed to view her unfavorably.”