You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

ORLANDO, Fla. -- John Barnhill told a joke that was much appreciated by admissions leaders gathered at the annual meeting of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers. High school grade inflation, he noted, can make admissions leaders look good. Each year, as the high school grade point average of admitted applicants gets higher and higher, he said, you can boast about how you are attracting brighter and brighter applicants. No need to mention grade inflation.

But Barnhill, assistant vice president for enrollment management at Florida State University, is clearly too honest to run with that. He gave a presentation that showed that high school grade inflation appears to be very much a factor in the rising GPAs of his university's applicants, and everyone else's. But while some in admissions bemoan the trend, saying it makes it difficult to trust high school grades, Barnhill isn't that worried.

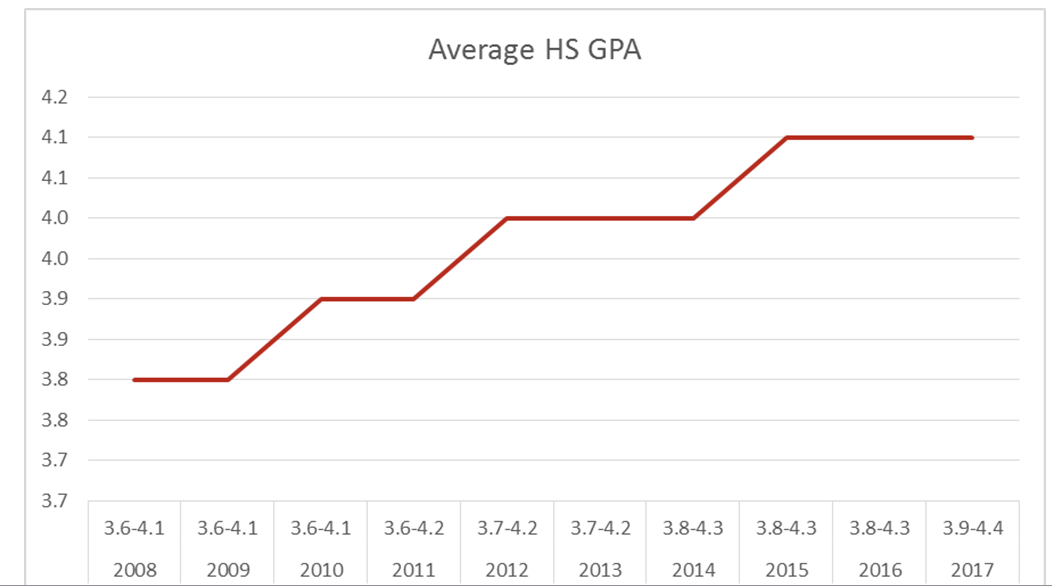

First, the data. He shared information about how the GPAs of his students are indeed rising just about every year (the figures at the bottom of the chart reflect the middle 50 percent of students).

Then Barnhill discussed why he doesn't think the grades reflect an increase in the brain power of his students (although he thinks they have plenty of that).

First off, SAT averages have not gone up to match the increased GPAs (leaving aside an increase in the last year that Barnhill attributes to the new version of the SAT).

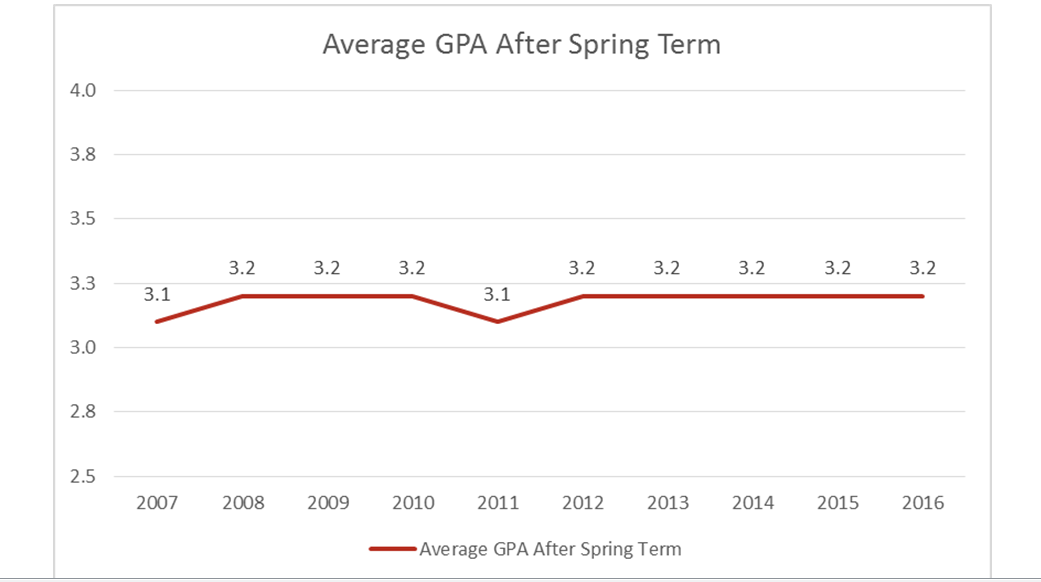

But then he looked at the grades earned by new Florida State students once enrolled. And they have been flat, suggesting a relatively stable level of academic achievement of Florida State students, despite the higher high school grades.

Barnhill then discussed some of the many reasons he thinks there is widespread grade inflation in high schools. He noted the trend of high schools weighting grades and coming up with more and more reasons to say that some A's are worth 4.5 or five points (honors, Advanced Placement and so forth). Florida State, like many colleges, deals with the inherent unfairness of different high schools using different systems by recalculating GPAs, using common rules.

Then there is the growth in "forgiveness," in which high school students who don't do well on a given test or assignment are given the chance to do it again, sometimes based on the teacher's wishes, and other times because parents have pressured the teacher to do so. What was once rare is now common, Barnhill said.

An additional source of pressure -- on students, parents and teachers -- comes from the many state scholarship programs that are based all or in part on high school grades. (Florida has the Bright Futures Scholarships.)

Parents are paying close attention to whether their children are at the levels needed to qualify, he said. And it is particularly difficult for high school teachers to withstand pressure when students and parents are saying that a low grade will mean the loss of a scholarship.

So what is one to do, especially when a university like Florida State has more than 51,000 applications to review?

Barnhill said the trend in grade inflation reinforces his view that "more is better" when it comes to information available to assess applicants. He urges his colleagues to pay more attention to junior-year grades than the entire GPA and to the trends in grades. He also urges more attention to grades by subject area, noting that mathematics grades are typically lower than those for other subjects, and said he doesn't want to punish those taking rigorous mathematics.

Florida State is also part of the College Board's pilot Environmental Context Dashboard, which is designed to help admissions offices get a better sense of the levels of poverty and opportunity for those in various neighborhoods. The idea is to evaluate students based on their actual opportunities, so a student who attends a high school with limited honors or AP options isn't viewed negatively compared to a student from a wealthier high school with numerous opportunities for AP courses.

Barnhill said that Florida State is already adjusting some admissions decisions because of its use of the dashboard.

So if Barnhill is convinced that high school grade inflation is real, why is he not that worried about the trend?

He looked at data Florida State collects on the "predictive validity" of various admissions criteria. In other words, do various factors predict whether an applicant will succeed academically in their first year at the university?

Looking at the study results for the classes that entered in 2009 and 2015 (a period of time with notable increases in high school grade inflation), Barnhill found that high school grades were and are the best way to predict college success. Grade inflation or not.

So even if there are reasons to worry about grade inflation, he said, it's not making admissions impossible. He termed this part of his presentation "the more things change, the more they stay the same."