You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

One of the internal documents released Friday by a group suing Harvard University over its admissions policies warned about the impact of having some details of those policies become public.

"We imagine that sharing any analysis of admission weights will draw attention to the variety of factors that compete with one another in the admissions decision. To state the obvious, with only 2,200 spaces for admitted students per year, implicit trade-offs are made between athletes and nonathletes, legacy admits and those without affiliation, low-income and other students," said an internal admissions office memo. "We know that many are interested in the analysis of the relative trade-offs. While we find that low-income students clearly receive a 'tip' in the admissions process, our descriptive analysis and regression models also shows that the tip for legacies and athletes is larger and that there are demographic groups that have negative effects."

The memo was prescient. With the release of numerous internal Harvard documents by the plaintiffs in the case, the university received strong scrutiny in the news media -- and may face tougher scrutiny from a federal court considering the lawsuit.

That's because the documents suggest that Harvard was aware that Asian-Americans are the primary group feeling "negative effects" of various admissions policies. The suit was brought by a group called Students for Fair Admissions, and it charges Harvard with using affirmative action policies that go beyond those legally permitted by several Supreme Court decisions. To the extent that the documents indicate substantially different admissions standards (for academic achievement) for applicants from different racial and ethnic groups, the evidence could be significant. The consideration of personality factors appears to substantially disadvantage Asian-American applicants.

Notably, however, the documents show that Asian-American applicants also lose spots because of policies that do not primarily benefit black or Latino applicants. Harvard's preferences for athletes and alumni children also result in fewer Asian applicants being admitted than would otherwise be the case, the documents suggest.

“Today’s court filing exposes the startling magnitude of Harvard’s discrimination against Asian-American applicants,” said Edward Blum, president of Students for Fair Admissions. “This filing definitively proves that Harvard engages in racial balancing, uses race as far more than a ‘plus’ factor, and has no interest in exploring race-neutral alternatives.”

Harvard of course knew what was in the documents, since it had turned them over under discovery requests in preparation for the trial, which is about to start. Just days before the documents were released, Harvard president Drew Faust sent the campus a message warning of the kinds of evidence to expect from the plaintiffs. "These claims will rely on misleading, selectively presented data taken out of context. Their intent is to question the integrity of the undergraduate admissions process and to advance a divisive agenda," she said.

And Harvard responded quickly Friday, arguing that the studies described in the various memos were preliminary analyses, with small samples, and did not reflect valid comparisons.

But for the plaintiffs, the evidence seemed to score public relations wins and suggested a stronger legal argument than it has presented to date. Until now, the plaintiffs have repeatedly shared analyses of the high SAT averages of Asian-American applicants, including those who are rejected in favor of those without equally high scores. With the release of the new documents, the plaintiffs can say that there are specific policies hurting Asian applicants.

Analyses That Raise Questions

Harvard has never denied that it considers race and ethnicity in admissions decisions, but it has always maintained that it uses race and ethnicity as one factor among many, including economic disadvantage, special talents and a range of other factors.

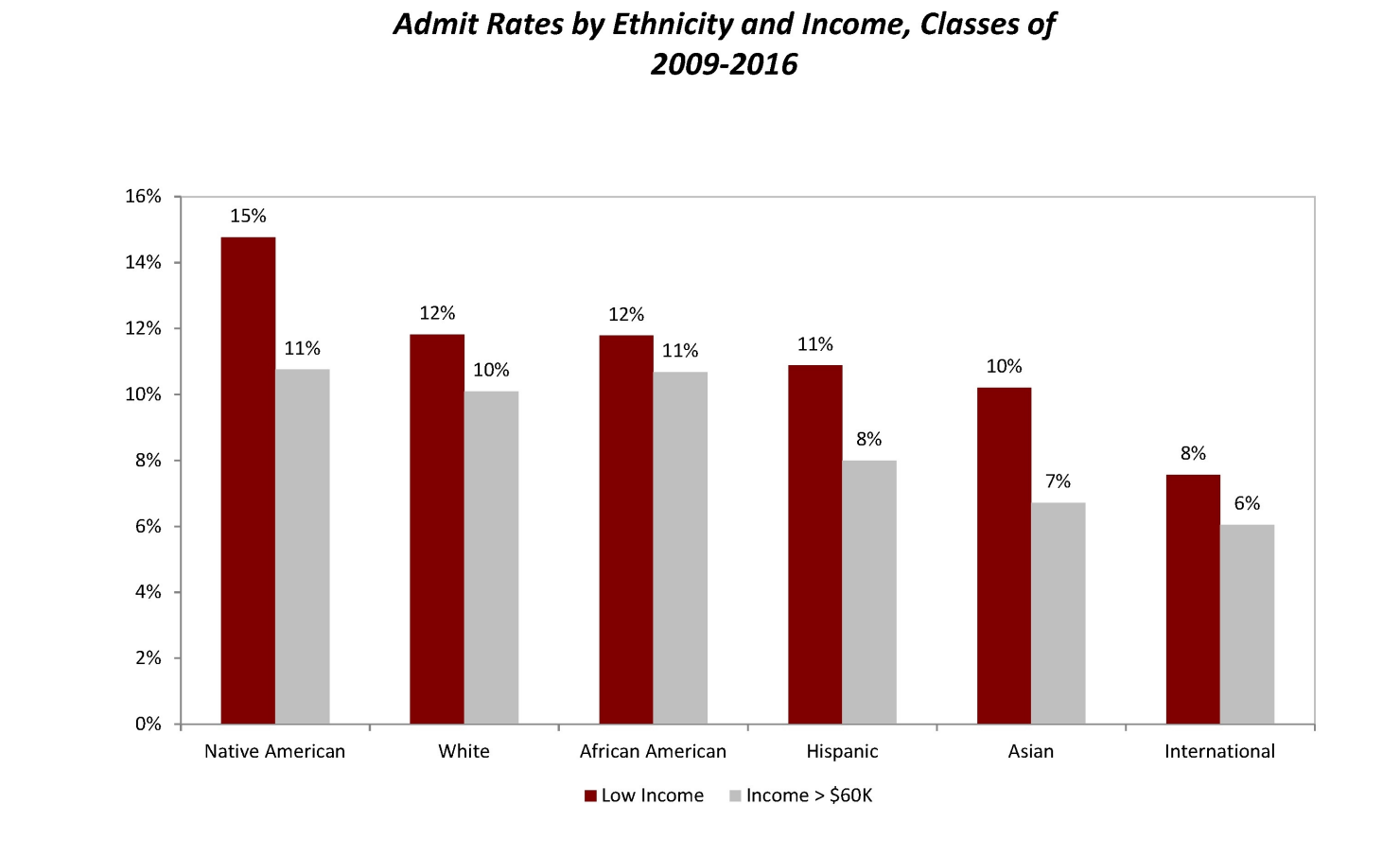

But some of the internal documents Harvard was forced to provide the plaintiffs suggest that Asian applicants may be at a disadvantage even when other factors are considered. Take, for example, low-income status, defined by Harvard as family income less than $60,000 a year. All groups that apply to Harvard are more likely to be admitted if they are from low-income families than from other families. But the rate is lower for Asian-American applicants from low-income families than it is for all other domestic groups. And low-income Asian applicants are less likely to be admitted than are higher-income black applicants, and they are equally likely to be admitted as are higher-income white applicants.

In considering the intersection of race and economic class, it may be worth noting other data in the Harvard documents, which show that a majority of applicants from all groups come from families earning at least $60,000. For Asian-Americans, the figure for those earning less than that was 18 percent, for black applicants the figure was 24 percent and for Latino applicants the figure was 25 percent.

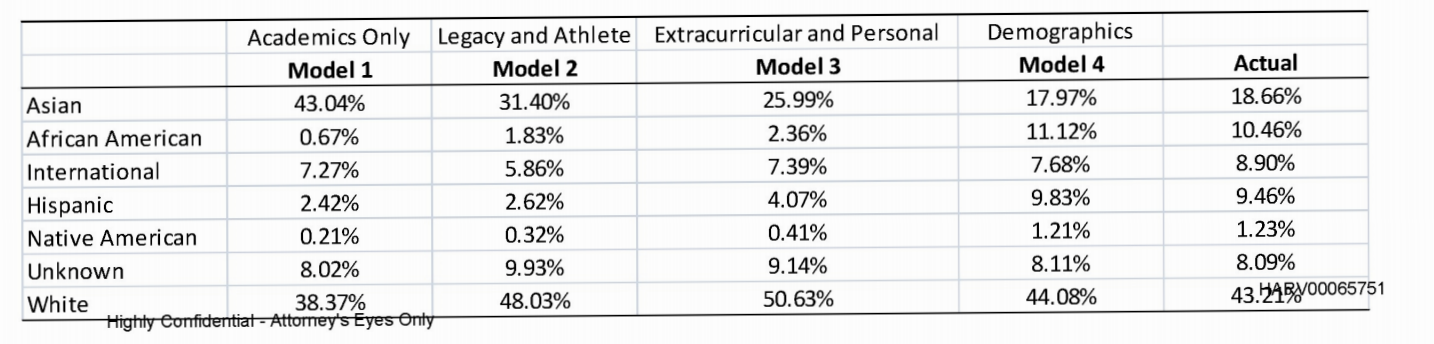

Or consider an analysis performed by Harvard after some public discussion in 2013 of the long-standing complaints by advocates for Asian-American students about their perception that they had to be better than other applicants to stand a chance at Harvard. The analysis compared the then-current makeup of the student body with what it would be based on other ways of determining who gets in. An "academics only" policy (focusing on grades and test scores) would have more than doubled the share of the class that was Asian and significantly cut the enrollment levels of black and Latino students.

National surveys by the National Association for College Admission Counseling show that admissions officers at four-year colleges say that grades, curricular rigor and test scores are by far the most important factors in admissions decisions. But such an approach may be more difficult at Harvard, where such a large share of the student body has perfect or near-perfect grades and test scores.

Students for Fair Admissions also obtained (after a court fight) six years of admissions data, with certain information redacted to protect the privacy of applicants.

The group had Peter Arcidiacono, a professor of economics at Duke University, do various analyses on the data files. He found consistent patterns for the treatment of Asian-American applicants with certain grades, test scores and other factors such that an Asian-American applicant with a 25 percent chance of admission would have a 35 percent chance if he were white, a 75 percent chance if he were Latino, and a 95 percent chance if he were African-American.

The information released by the plaintiffs suggests that they are making the case that Harvard has a two-tiered (or multiple-tiered) admissions process in which Asian-Americans are evaluated in different (more stringent) ways. That is significant because it would run counter to what the Supreme Court has permitted -- which is holistic review in which race and ethnicity are considered, but only as part of an in-depth review considering many factors, in which students of all groups have a fair shot. In other words, the Supreme Court is not bothered by an applicant from an underrepresented minority group being admitted over another applicant with higher grades and test scores. But both must be evaluated under essentially the same system.

Another part of the Supreme Court's guidance on affirmative action that the plaintiffs are applying to Harvard is the requirement that institutions that want to consider race or ethnicity in admissions or other decisions first consider whether race-neutral approaches might yield sufficient levels of diversity. On this issue, the plaintiffs submitted a brief by Richard D. Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation and a long-standing advocate of using class-based affirmative action rather than race-based affirmative action.

Kahlenberg wrote that he provided Harvard with approaches -- rejected by the university -- that would have kept much (but not all) of the current enrollment levels of black and Latino students while increasing the enrollment of low-income students. He said that this could be done several ways, either by explicitly considering economic status but not race, or through "place-based" affirmative action, in which preference would be granted to those who live in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Whether a court will find the evidence damning of Harvard remains to be seen, but the documents released had many people -- beyond Students for Fair Admissions -- wondering about Harvard's policies.

Robert Zimmer, president of the University of Chicago, was asked about Harvard's policies during a session Friday at the meeting of the Heterodox Academy, a group seeking to encourage more viewpoint diversity in higher education.

He said he didn't know the details of Harvard's admissions procedures but was concerned by the idea that "definitions of character" or evaluating personalities would result in candidates of superior academic quality being rejected. He noted that for much of the first half of the 20th century, "these character issues and definitions of character were put in place to keep Jews out of Ivy League institutions." And he said that if colleges evaluate personality characteristics, they should "constantly" ask why they are favoring certain characteristics over others.

At Slate, Aaron Mak wrote that he understood why many people are dubious that Students for Fair Admissions really cares about Asian-American students.

Blum and his organization are "exploiting" the fears of Asian applicants "for the benefit of white applicants," Mak wrote. "If he succeeds in outlawing race-conscious factors, then people of color who are already dramatically underrepresented in higher education will further fall behind in an admissions game that often advances racial privilege. At the end of the day, it would be ruinous if Harvard lost the case and the courts banned affirmative action."

But Mak took Harvard to task for not revealing the studies earlier and talking more openly about how it promotes diversity and the impact of its policies on Asian-American applicants.

"The findings suggest that there is a healthy dose of implicit bias influencing the admissions process," Mak wrote. "The allegations that Harvard decided to bury the findings from the 2013 internal investigation are perhaps more damning, because they are indicative of a distaste for transparency that will only serve to exacerbate suspicions that admissions officers are set on restricting the number of Asian-American students. It could well be the case that allegations of bias against Asian-Americans are overstated, but we won’t know that for sure unless Harvard and other universities are more open about their admissions processes."

‘Dangerous Ploy’

Defenders of affirmative action have since the release of the documents been stressing one of the issues raised in the Slate piece: that the ultimate goal of Students for Fair Admissions is to end affirmative action in higher education generally. (Blum freely admits that he thinks the Supreme Court decisions upholding affirmative action were decided incorrectly, but his arguments in this case are based on his view that Harvard isn't following those decisions.)

Jin Hee Lee, deputy director of litigation at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, issued this statement: "The college admissions process must be equitable and inclusive in order to ensure a comprehensive assessment of prospective students’ talents and potential. This lawsuit filed by Edward Blum in the name of Asian-American students is a dangerous ploy to distort the benefits of diversity for college students of all races, despite settled law on this issue."

Susan M. Dynarski, a professor of economics, education and public policy at the University of Michigan, has been following the case. She said via email that the documents released by Students for Fair Admissions were not "new statistical evidence" but were "a PR move by the plaintiffs."

Of the various studies referenced in the plaintiffs' filings and above in this article, she said, "The internal analysis is an extremely rough cut at the data. It lacks important variables. And, unsurprisingly, it lacks the nuance of the analyses by tenured social scientists. There are a lot of modeling choices to make here."

Harvard released an FAQ late Friday responding to some of the questions raised by the documents released by the plaintiffs. In various answers, Harvard asserted that the studies referenced by the plaintiffs were preliminary and did not reflect the full picture. Further, the university argued that the various models used by the plaintiffs were unfair to focus solely on the results that would be achieved with a purely academic review of applicants.

"Mr. Blum’s case hinges entirely on a statistical model that deliberately ignores essential factors, such as personal essay or teacher recommendations, and omits entire swaths of the applicant pool (such as recruited athletes or applicants whose parents attended Harvard) to achieve a deliberate and pre-assumed outcome," the Harvard statement says. "Months of investigation failed to produce any documentary or testimonial support for [Students for Fair Admissions'] accusation that Harvard intentionally seeks to limit the number of Asian-Americans or discriminates against them."

Harvard is also pushing back against the idea that test scores alone suggest who should be admitted. The debate at Harvard comes as New York City mayor Bill de Blasio has proposed moving New York City's top public high schools away from an admissions system based solely on a standardized test, a system that has led to disproportionate Asian enrollments at those schools.

In an answer to a question on standardized tests, the university says that "Harvard College seeks to bring together a class that is excellent and diverse on many dimensions, and standardized test scores are only one aspect of a whole-person review."

And Harvard is also rejecting the idea that the treatment of Asian applicants today matches that of Jewish applicants, who faced quotas and bias at Harvard in earlier generations.

Said Harvard's FAQ: "These unfortunate events from 100 years ago are a dark chapter in Harvard’s history. For many years, we have been committed to evaluating the whole person and we consider each applicant’s unique background and experiences, alongside grades and test scores, to find applicants of exceptional ability and character, who can help create a campus community that is diverse on multiple dimensions, including academic and extracurricular interests, racial and ethnic background, and life experiences."