You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

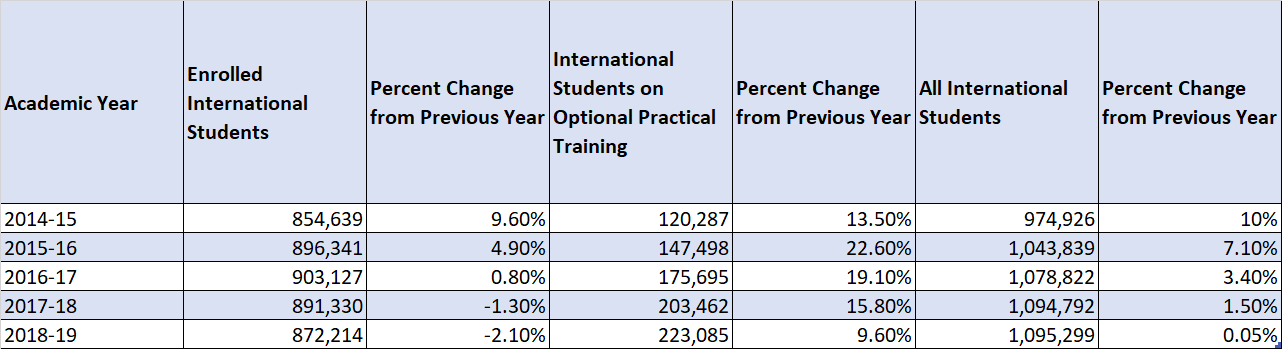

The number of enrolled international students at American colleges and universities decreased at all academic levels -- undergraduate, graduate and nondegree -- in the 2018-19 academic year, according to new data from the "Open Doors" report.

The number of international undergraduate students declined by 2.4 percent, the number of international graduate students declined by 1.3 percent and the number of international nondegree students declined by 5 percent.

Study Abroad on the Rise

Number of U.S. students enrolled

abroad increased 2.7 percent in

2017-18, continuing steady growth.

Read more here.

Despite these drops, the total number of international students in the U.S. actually increased slightly, by 0.05 percent, due to a 9.6 percent increase in the number of international students participating in optional practical training, a program that allows international students to stay in the U.S. to work for up to three years after graduating while staying on their student visas.

Total International Students in the U.S.

The number of new international students also decreased for the third straight year, but the 0.9 percent decline in new international enrollments in 2018-19 was smaller than declines of 6.6 and 3.3 percent reported the two years prior.

The "Open Doors" report, published annually by the Institute of International Education in cooperation with the U.S. Department of State, is based on a survey of international enrollments across more than 2,800 institutions.

A separate "snapshot" survey of fall 2019 enrollments across more than 500 institutions released today by IIE likewise reports an average 0.9 percent decline in new enrollments continuing this fall.

About 51 percent of institutions responding to the snapshot survey reported decreases in new international enrollments, and 42 percent reported increases, with the remaining 7 percent reporting no change. Over all, research universities reported increases in new international enrollments this fall, while master’s institutions and institutions in the Midwest reported decreases.

Business Down, Math and Computer Science Up

A notable change in the "Open Doors" data for the 2018-19 academic year was that math/computer science surpassed business/management as the second-most-popular field for international students, after engineering. The number of students studying math and computer science increased by 9.4 percent, while the number studying business fell by 7.1 percent. (International enrollments in engineering decreased by 0.8 percent.)

A recent report from the Graduate Management Admission Council warned of waning international interest in U.S. business schools, and identified as key to this declining interest visa and immigration policies that can limit the ability of international students to stay and work long term in the U.S. The report also discussed the effects of anti-immigrant rhetoric and concerns on the part of prospective students about safety and security. Fifty-four percent of prospective students from India and 50 percent of students from China who were surveyed in 2018 said that the political environment would prevent them from applying to a U.S. business school.

“The cost of a graduate business education is one of the largest investments that a student will make; making that investment in an economy that is perceived to be not only uncertain, but also unwelcoming, is a growing risk for many international students and one that fewer are choosing to make,” says the GMAC report, which was issued in October.

NAFSA: Association of International Educators issued a report in May warning about declines in international enrollments at American colleges and universities more generally (not just in business schools). "University and industry leaders acknowledge that anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies contribute to a chilling effect on international study in the United States," the NAFSA report states.

Undoubtedly, a large number of factors have contributed to the declines in international enrollments at U.S. universities, including issues of cost and competition from other destination countries, improvements to capacity and/or quality of universities in students' home countries, macroeconomic or demographic changes in sending countries, and changes to foreign government scholarship programs, most notably the contraction of a large Saudi Arabian government scholarship program that was responsible for unprecedented growth in the number of Saudi students coming to the U.S.

Rahul Choudaha, an international education analyst and blogger at DrEducation, said there's no question what's often been called the "Trump effect" has played a role in the international enrollment declines, though it is not the only factor.

"This is like a cascading effect, he said. "We are talking about the consistent deceleration in enrollments since 2015-16, when peak new enrollment was hit. From there to where we are now, that’s a significant loss of potential for U.S. higher education, and a lot of it can be attributed to what changed in the external environment. The quality and intentions of institutions to attract international students remain positive, so the one common factor you can isolate very easily is what changed in policies for immigration and visas. There were already some challenges form the competitive environment, then the radical shift in the outlook for the U.S. as a study destination just made things worse for the students and institutions."

In a press call, officials with IIE and the State Department addressed the perception that President Trump's policies and rhetoric may have contributed to the decreases. They suggested a more relevant factor is the relatively high cost of U.S. higher education.

"Everywhere I travel, talking with parents and students, the No. 1 concern they have is about cost. American higher education is expensive -- it is more expensive than other countries. I'd say there’s always a mix of factors that go into deciding who will come, where they’ll come, where they’ll go, but overwhelmingly that is what is most on parents’ minds," said Allan E. Goodman, the president and CEO of IIE.

"The trends that we have seen with international student mobility started in 2015, which means that students were filling out their applications under a different administration," said Caroline Casagrande, the deputy assistant secretary for academic programs in the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs. (The first decline in new enrollments was reported in academic year 2016-17.) "What we’ve seen today is a dramatically better picture compared to last year’s declines, where we had a decline of 6.6 percent [in new international enrollments], and that stabilized to a drop of 0.9 percent.”

State Department officials said the Trump administration was investing in increasing international enrollment and conveying the message that international students are welcome.

"The U.S. Department of State is allocating more resources than ever before to encouraging international student mobility," said Marie Royce, the assistant secretary of state for educational and cultural affairs. "Through our Education USA network [of educational advisers] we’re expanding our centralized marketing resources to promote the United States as the world’s top study destination. We are currently working on a high-quality global marketing campaign that will further refine our materials, hone our messaging and expand our contacts in priority markets around the world. The Bureau of Education Educational and Cultural Affairs is also engaging with key markets like China, India, Colombia and Brazil. Through interactions with students and parents and through print, radio and TV interviews, we are reinforcing the message that we welcome international students.”

Trends by Country and Institutional Type

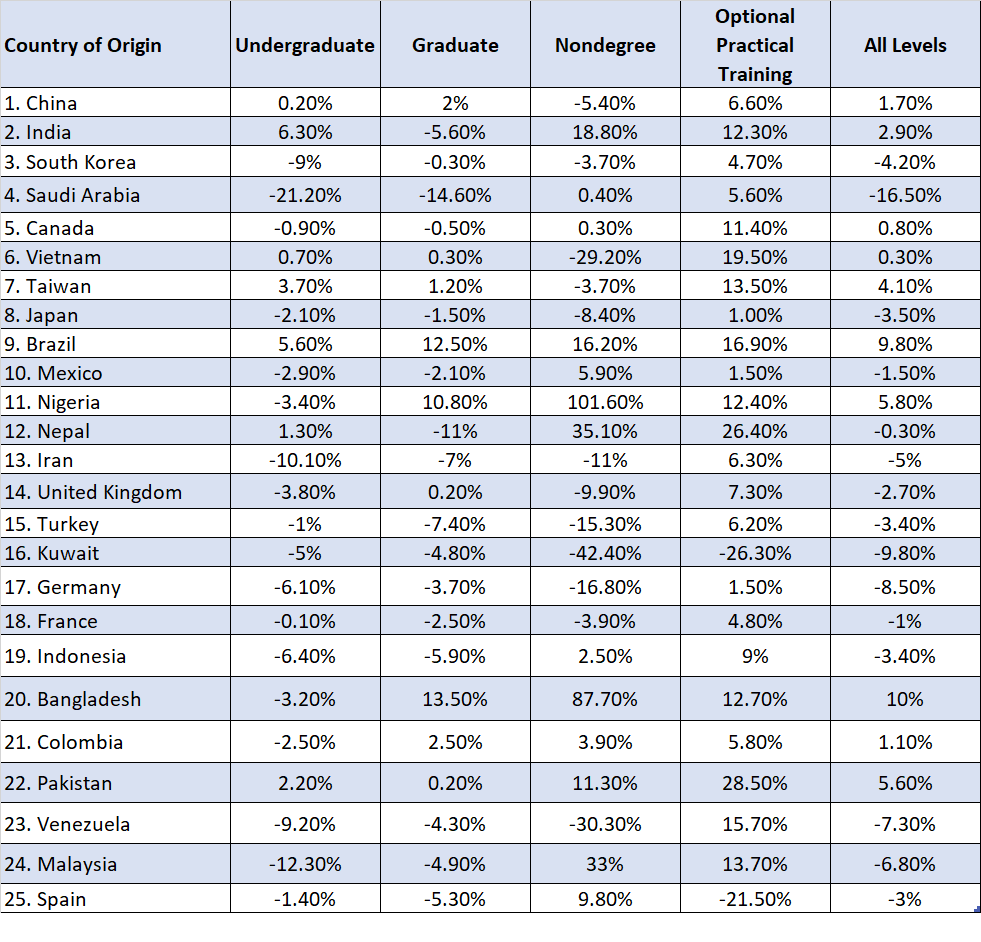

Among the notable changes in new international enrollments, the number of students from the No. 1 sending country, China, increased by 1.7 percent in 2018-19, with Chinese graduate enrollments increasing by 2 percent and Chinese undergraduate enrollments increasing by a modest 0.2 percent. The number participating in nondegree study, a category that includes intensive English programs, decreased by 5.4 percent, while the number of Chinese students on OPT increased by 6.6 percent.

Among the notable changes in new international enrollments, the number of students from the No. 1 sending country, China, increased by 1.7 percent in 2018-19, with Chinese graduate enrollments increasing by 2 percent and Chinese undergraduate enrollments increasing by a modest 0.2 percent. The number participating in nondegree study, a category that includes intensive English programs, decreased by 5.4 percent, while the number of Chinese students on OPT increased by 6.6 percent.

The number of students from the No. 2 country of origin, India, increased by 2.9 percent, though the story behind that overall number is mixed: there was a big increase in the number of students from India on OPT (12.3 percent), but the number of Indian students enrolled at the graduate level declined by 5.6 percent. About four times as many Indians study in the U.S. at the graduate level than at the undergraduate level, but the undergraduate student population from India is growing: undergraduate Indian enrollments grew by 6.3 percent in 2018-19.

Together, students from China and India account for more than half (52.1 percent) of all international students studying in the U.S., so even small shifts in the sizes of these student populations can make big differences to colleges. U.S. universities have come to depend financially on growing cohorts of tuition-paying Chinese undergraduate students, whose numbers more than quadrupled over the past decade. But after a decade of robust growth, some colleges are anecdotally reporting declines in Chinese undergraduate enrollments this fall, and there's no question from the 2018-19 "Open Doors" data that growth in Chinese undergraduates has essentially stagnated.

Meanwhile, the number of students from the No. 3-sending country, South Korea, declined by 4.2 percent, a continuation of a long-term trend driven in part by demographic changes and the development of South Korea’s own higher education system. The academic year 2018-19 represented the eighth straight year of declines in South Korean students at U.S. colleges.

The number of students from No. 4 country Saudi Arabia decreased by 16.5 percent in 2018-19, following on a 15.5 percent decline the year before and a 14.2 percent decrease the year before that. The number of students from Saudi Arabia has contracted sharply as the government has scaled back support for its large-scale overseas scholarship program.

Rounding out the top five countries of origin for international students, the number of students from No. 5 Canada increased by 0.8 percent, fueled by a 11.4 percent increase in Canadian students on OPT, but there were drops at the undergraduate (-0.9 percent) and graduate level (-0.5 percent).

Outside the top five, Mirka Martel, the head of research, evaluation and learning at IIE, said the organization has "seen positive increases in a number of emerging market economies across Latin America, Africa and Asia."

"For example, we saw international students from Bangladesh increase by 10 percent, from Brazil by 9.8 percent, from Nigeria by 5.8 percent. More institutions are expanding their outreach in more regions … and this growth demonstrates how attractive education at U.S. institutions is for students from around the world," Martel said.

Among the top 25 countries of origin, there were also increases in the total numbers of students coming from Vietnam (+0.3 percent), Taiwan (+4.1 percent), Colombia (+1.1 percent) and Pakistan (+5.6 percent). And there were decreases in the numbers of students coming from Japan (-3.5 percent), Mexico (-1.5 percent), Nepal (-0.3 percent), Iran (-5 percent), the United Kingdom (-2.7 percent), Turkey (-3.4 percent), Kuwait (-9.8 percent), Germany (-8.5 percent), France (-1 percent), Indonesia (-3.4 percent), Venezuela (-7.3 percent), Malaysia (-6.8 percent) and Spain (-3 percent).

It's important to note that trends can vary across institutional levels. For example, for Vietnam, which many colleges have looked to as a promising source country for growth in international enrollments, international undergraduate and graduate enrollments increased slightly (by 0.7 and 0.3 percent, respectively), but nondegree enrollment fell by 29.2 percent. Growth in OPT participation for students from many countries continues to prop up the top-level enrollment number even when there are declines or slower rates of growth at undergraduate, graduate or nondegree levels.

Finally, it's important to note that the overall trend lines for international enrollments in the U.S. varied across institution types. International enrollments increased by 1.2 percent at doctoral universities and by 2.1 percent at baccalaureate colleges, while master's level-institutions reported a 1.3 percent decline. The biggest drop was at associate-level institutions, where total international enrollments fell by 8.3 percent in 2018-19.

Percentage Changes in International Enrollments from 2017-18 to 2018-19, by Level and Top 25 Countries of Origin