You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Justice Department

The U.S. Justice Department has backed key arguments made in an antitrust suit against 16 private colleges and universities.

In a brief filed Thursday, the department did not seek to join the suit but said it was stating “the interest of the United States.” Specifically, the brief is an answer to a motion by the colleges to dismiss the case.

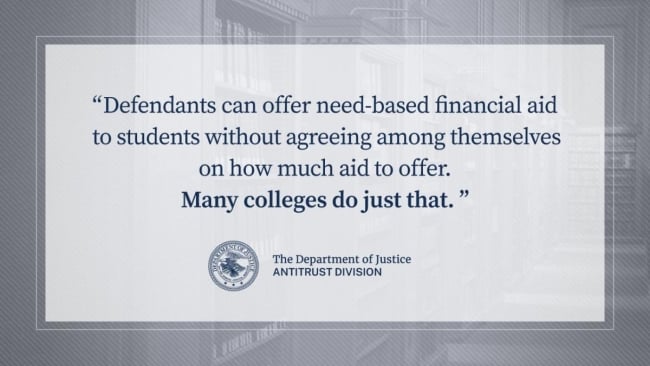

The colleges accused of violating antitrust law defend their action by citing the “568 Exemption” for colleges that admit all their students in a need-blind way. But the Justice Department says that “an agreement between schools that admit all students on a need-blind basis and schools that do not is beyond the scope of the 568 Exemption. Thus, to the extent that at least some of the defendants do not admit all students on a need-blind basis, the 568 Exemption would not apply here.”

The targets of the suit are Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Duke, Emory, Georgetown, Northwestern, Rice, Vanderbilt and Yale Universities; the California Institute of Technology; Dartmouth College; the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and the Universities of Chicago, Notre Dame and Pennsylvania.

All these colleges say they are need blind.

But the suit says, “At least nine defendants for many years have favored wealthy applicants in the admissions process. These nine defendants have thus made admissions decisions with regard to the financial circumstances of students and their families, thereby disfavoring students who need financial aid.”

The nine are Columbia, Dartmouth, Duke, Georgetown, MIT, Northwestern, Notre Dame, Penn and Vanderbilt. The suit charges that they “have failed to conduct their admissions practices on a need-blind basis because all of them made admissions decisions taking into account the financial circumstances of applicants and their families, through policies and practices that favored the wealthy.”

Columbia University is criticized because its School of General Studies, which the suit says enrolls 2,500 undergraduates, doesn’t have need-blind admissions, according to the suit. “The burden of supporting Columbia’s preservation of prestige and financial accumulation therefore falls on those who can least afford it,” the suit says.

The Justice Department brief also cites the suit it filed in 1989 (and won) against the Ivy League universities and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The Ivy League universities settled the suit, while MIT fought it and lost.

When the department first opened that investigation, many at colleges were shocked. But the statement in the suit marks the third time (counting a suit against the National Association for College Admission Counseling) that the department has been involved in litigation against colleges on antitrust matters. And the department has been involved during three administrations: that of the first President Bush, President Trump and President Biden.

Robert D. Gilbert, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, said, “We are very pleased that the Department of Justice has filed this statement supporting plaintiffs on the key issues in this case.”

The colleges involved have not commented on the case.

NACAC issued this statement: “We will monitor the suit and help college admission counseling professionals understand any potential implications.”

Some academics have criticized the recent suit against the 16 colleges, arguing that it distorts antitrust law’s purpose.

Phillip B. Levine, the Katharine Coman and A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Economics at Wellesley College, wrote an opinion piece for Inside Higher Ed in February that said, “Cartels fix prices. They make things more expensive. That is what OPEC did to gas prices in the 1970s. Recently, a group of elite colleges (the 568 Group) has been charged with acting like a cartel to fix prices students pay by unfairly limiting the amount of financial aid they could receive. It turns out, though, these institutions already charge lower prices to lower-income students than do other colleges and universities because they have far more resources available to do so. Other institutions will only have the capacity to lower prices for lower-income students when provided the appropriate resources to afford it.”

In an interview Friday, Levine said he still maintains that view. He said via email, “The ultimate goal of antitrust policy in higher education should be to lower prices, particularly for lower-income students. Member institutions of the 568 Group already charge those students considerably lower prices than other institutions.”