You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

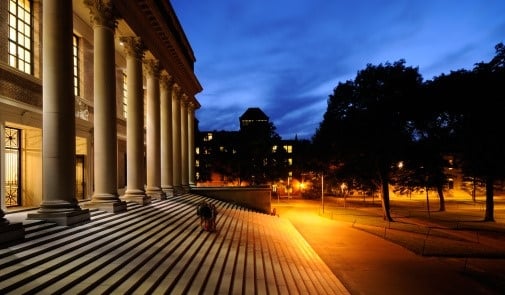

Harvard University

jorgeantonio/Getty Images

Once again, elite institutions are sucking the air out of the college admissions newsroom. Students, with their hopes bolstered by test-optional policies, have sent applications to the most selective private and public colleges skyrocketing. “I might have a chance this year” is the mantra.

But not so fast, my friends.

Wait lists are up … way up. A new national poll shows that 20 percent of students making college choices are now on a wait list. Sadly, a disproportionate 29 percent of students who identify as Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) are wait-listed.

The expanded applicant pool at top-ranked institutions was an extraordinary opportunity for them to step away from the elitism that has the Ivy league, for example, enrolling more students from the top 1 percent of the income distribution than they enroll in the entire bottom half. Instead, we see expanded wait lists, particularly for people of color.

Are the elites doing their share to educate the nation? No, they are not.

Chartered in the public trust and wealthy well beyond the normal college or university, there is every reason to expect that they should be serving much higher proportions of low- and moderate-income students and other populations like the BIPOC students on wait lists.

A recent opinion piece by David Kirp, author of Shakespeare, Einstein and the Bottom Line, suggested that the Ivies should expand and create branch campuses -- Yale University in Houston, for example -- to expand access to a high-quality education.

But location is not the constraint -- these institutions could already be choosing to be more inclusive in their current locations. If they moved to Houston and admitted more of the same type of student (read: wealthy and white), what difference would it make?

The solution is not branch campuses for the elite but to reward all colleges and universities that have the will to serve the changing citizenry and workforce of America. To do this we need a new partnership between the federal government and higher education that would provide per-student subsidies to institutions in exchange for annual progress in the admission, funding and success of low- and moderate-income students. The burden of proof would be on institutions until such time that social mobility indicators, including both the numbers of low- and moderate-income students enrolling and graduating, are markedly improved.

Virtually all the growth in the college-aged population over the next two decades will come from groups who are currently excluded from or being served less well in the current system. Our nation’s health, economically, politically and socially, depends on educating a far broader swath of society than we do today. We need to look past the great and powerful institutions behind the curtain and offer solutions that will ensure broader and more successful enrollment across all sectors of higher education for the good of our nation.

Like many scholars who are concerned about equitable access and completion rates in postsecondary education, I am pleased to see that the Biden administration is off to a promising start by offering infrastructure plans to bolster colleges that serve underrepresented populations, promoting free community college and considering a doubling of the national Pell Grant program that offers financial aid to low-income students.

Refreshingly, these ideas signal a recognition that the colleges that most serve first-generation, low-income and students of color are the community colleges, the regional public campuses and the many hundreds of unsung small private colleges. However, the proposals will pump billions of additional federal dollars into the higher education sector but don't appear to be paired with adequate safeguards to ensure proper targeting and good outcomes. Simply pouring more money into our current system of vouchers -- which provide more than $120 billion in aid to students -- is unlikely to produce better results or, for that matter, improve affordability if college prices continue to outpace available aid.

If new money is to come, it must be tied to results. The system of higher education, from institutions that are open access to those that are highly selective, needs to be accountable for doing better than it does today. Elite and less elite schools alike need to admit and graduate more low- and middle-income students. Enlightened education policy is the lever to get this done.

With funding from the Joyce Foundation, I have been convening a group of researchers and federal, state and institutional policy makers to focus on effective ways to increase the number of low- and moderate-income students that enter college and graduate. We now believe that what is needed is greater funding for most institutions and accountability for all of them.

We need to establish thresholds for eligibility for the receipt of additional federal dollars, targeting those institutions that are currently underfunded and can improve outcomes with greater resources. We can ensure that these resources yield the desired outcomes by identifying the percentage of low- and moderate-income students that will need to be enrolled, along with targets for graduation rates. More resources and accountability will help address the problem of all the attention falling on the elites, by essentially making them less elite and improving outcomes across the rest of higher education.

More importantly, it is imperative that we help less advantaged students climb the escalator toward upward mobility. As a nation we will be acting in enlightened self-interest. Our economy and our democratic institutions need them. It is time to stop chasing Ivy and to start educating the fullness of the nation.