You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

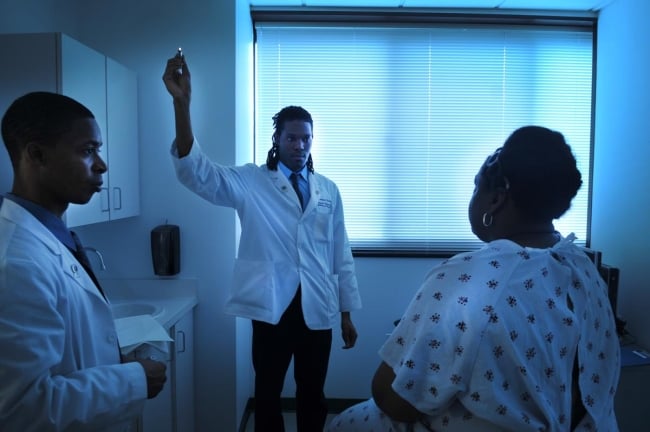

Howard University

For decades, the stagnating number of Black male medical students was one of the most alarming narratives in health care. Across the entire country, more Black men applied to medical school in 1978 (1,410) than in 2014 (1,337). And as of 2018, only 5 percent of doctors in America were Black, with a single school—Howard University—responsible for training half of that number.

But last month, the Association of American Medical Colleges reported that, for fall 2021, Black first-year medical student enrollment increased by 21 percent, with Black male enrollment increasing by 20.8 percent. This is good news.

However, in order to sustain this growth, we need structural changes to the medical school admissions process that will eradicate still-present bias and discrimination.

The review of an applicant’s qualifications should be holistic and objective. That entails gathering as much data as possible while also selectively withholding certain information at particular stages of the admissions process to mitigate the effects of bias.

The initial application that all medical school receive from each applicant includes, among other information, MCAT scores and undergraduate grades. An overemphasis on those metrics can obscure other important applicant characteristics that can be just as revealing of their future success in medical school and beyond.

To paint a more complete picture of the applicants, many medical schools use a secondary application. At Howard University College of Medicine, we ask whether they are from, have connections to, or plan to work in underserved communities. We also examine applicants’ Pell Grant status, the educational and occupational levels of their parents, family size and income, and more.

Many medical schools are now electing to remove the academic metrics from the reports that members of the admissions committee receive prior to interviewing applicants in order to limit bias. When the interviewer is blinded to that information, they are more likely to evaluate the applicant objectively and identify other important characteristics, such as how they overcome adversity.

At Howard University College of Medicine, we received 7,502 applications for students applying to matriculate in fall 2021 (a record for our institution). We made admission offers to 4.3 percent of applicants, and 122 new applicants matriculated. Despite how competitive our school has become and the limited positions we have available, 79 of our new enrollees were only admitted to one medical school—ours. Whether they were rejected from other schools or finances prevented them from applying to other institutions, the majority of our students would not have attended medical school this fall had we not accepted them. We are proof that, with the right admissions process, even exclusive and selective institutions can be accessible to anyone, not just the privileged.

Over the past five years, the average MCAT score for incoming classes at Howard’s College of Medicine was 503, slightly below the national mean of 510 over that same period. By examining our own student success data, we have seen Black students at our school with slightly lower MCAT scores are graduating or matching at similar or higher rates compared to Black students at other institutions.

While news of increasing diversity in medical school classes was certainly welcome, it was largely greeted with cautious optimism. There is much concern that these numbers could ultimately reflect an anomaly rather than the beginning of a long-term trend.

Additionally, after Black medical students successfully enroll, we must do more to provide financial and emotional support to ensure they graduate. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine have assembled a roundtable of experts to study the factors that prevent Black individuals from pursuing and continuing their STEM educations and the solutions that can help them overcome or bypass these challenges. From the negative stereotypes and entrenched biases they encounter to the overwhelming debt burden they have to take on to attain their degrees, the roundtable is exploring how psychological and financial support can improve Black medical student enrollment and graduation rates.

Medical schools, and all institutions of higher education, are stronger when they are diverse. It is vital that aspiring physicians encounter individuals from a variety of racial and socioeconomic backgrounds so they can deliver culturally competent care for their patients. In Howard’s medical school Class of 2025, 29 percent of matriculants came from Howard undergrad, 13 percent from other HBCUs, 8 percent from the Ivy League. Seven percent are international, and 69 percent are economically disadvantaged.

For medical schools that prioritize diversity, it doesn’t mean that we aren’t seeking the strongest candidates—our processes just help us broaden the lens so we can find the best applicants that other schools tend to overlook.

I encourage other medical schools to adopt bias-reducing admissions processes to eliminate discrimination and maximize inclusivity in academic medicine.